A Bohemian life – through the eyes of Mick Morgan

As a goalkeeper little is more important that being in the right place at the right time. No one wants to be all at sea, watching helplessly as a ball arches overhead and into the goal. The ball nestling accusingly in the back of the net, the criticisms of the crowd ringing in a ‘keeper’s ears, whether its his fault or not the keeper bears the brunt. However, when you’re in the right place at the right time, the slightest tip of a gloved finger sending the ball over the bar and away from danger the keeper becomes the hero, the last line of defence, the glory, fleetingly, is theirs.

At Bohemians we pride ourselves on being a bit different, the clue is in the name. In the reductive dictionary description a Bohemian (noun) is described as a “socially unconventional person”. Through this blog I’ve tried at times to demonstrate this unconventionality through the stories of some significant individuals from the past. And surely the most Bohemian, most unconventional of players is the goalkeeper? Jonathan Wilson in his wonderful examination of the goalkeeper’s lot named his book The Outsider, taking inspiration not only from the keeper’s role on the pitch but from the title of the Albert Camus’ novel. Camus grew up in North Africa, the son of a Spanish mother and a French father and was himself a useful goalkeeper.

Bohs have been lucky over the years to have been blessed with a great array of goalkeepers, recognised not only for their sporting talents but their big personalities. We have a truly impressive collection of great “Outsiders” dating back to the likes of Jack Hehir an Irish international whose Bohs career was interrupted after a mysterious summons for an “important appointment” to the War Office in 1915 through to the likes of Mick Smyth, Mick O’Brien (of crossbar destruction fame) Dermot O’Neill, Dave Henderson, one-season-wonder Ashley Bayes, Brian Murphy and on down to present day Shane Supple. And then of course there is Mick Morgan, a man, depending on how you look at it either in the right place at the right time or the wrong place at the wrong time.

For you see you can’t really tell the story of Mick Morgan, a Bohemian F.C. goalkeeper between 1930 and 1936 without also telling the story of Harry Cannon as Mick’s fortunes were so much intertwined with the peaks and troughs of perhaps Bohemians greatest ever goalkeeper, Captain Harry Cannon. That Morgan was a talented ‘keeper and spent six years at Bohemians yet managed to make only around 50 first team appearances due to the prominence of Cannon in the Bohemian goal tells its own story. However, it was due to Cannon’s success as an all-round sportsman and administrator that presented the opportunity for Morgan to make the bulk of those appearances, including a number of games against quality European opposition.

Cannon was an Irish Army officer who made his Bohemian debut in 1924 at the age of 27 and wouldn’t make his final appearance for Bohs until after his 40th birthday. During this time he was also capped twice by Ireland, against Italy in 1926 and in a 4-2 win against Belgium in 1928 when Cannon saved a penalty. At club level he would win four league titles and two FAI Cups for the Bohs.

Being the understudy to one of the most dominant and consistent goalkeepers in the league couldn’t have been an easy task, especially at what was then an amateur club. Several men filled this role in the more than a decade of Cannon’s dominance but one of the most talented and interesting is Mick “Boysie” Morgan who got the chance to make his mark for Bohemians due to the extra-Bohemian sporting activities of Captain Cannon.

The North Circular, the Lock-out and early sporting passions

Michael Morgan was born in November 1910 to Joseph and Mary Morgan at 35 Avondale Avenue just off the North Circular Road and only a short distance from Dalymount. Both of Michael’s parents were originally from County Meath. Joseph worked as a tram conductor and was one of those transport workers who suffered the deprivations of the 1913 Dublin Lock-out before passing away in December 1916 of tuberculosis at the age of just 33. Michael’s mother Mary was greatly affected by her husband’s early death and her son was sent to live with relatives in Dunboyne.

It was while living in Dunboyne that Michael first rose to sporting prominence, somewhat surprisingly as a Meath hurler. As a 14 year old he was part of the 1924 Dunboyne team that won the Meath Junior hurling title. Included among his hurling teammates was John Oxx Senior who would go on to find greater fame as a racehorse trainer.

Mick’s time as a hurler was short lived however, he had a passion for sports beyond Gaelic Games and fell foul of the infamous GAA Rule 27 which prohibited the playing or watching of “foreign games” like rugby, association football, cricket and hockey. By 1929 when Mick would have been 19 he was double jobbing as a hurler for Dunboyne while playing in goal for Leinster Senior League side Strandville F.C.

Strandville took their name from Strandville Avenue off Dublin’s North Strand and were a team of some prominence. For example Oscar Traynor who achieved fame and on-field success as a goalkeeper for Belfast Celtic had played for Strandville pre-1910. Traynor became a prominent Republican during the War of Independence as a Brigadier in the Dublin Brigade of the IRA. He would later become a government Minister and was President of the FAI for almost thirty years until he passed away in 1977.

Morgan developed a sufficient profile for Strandville to be signed up by Bohemians, joining the club in March of 1930. According to his son, also Michae,l his signing for Bohs was somewhat fortuitous. As an ambitious young keeper, always eager to improve aspects of his game Mick Morgan used to go to the Connaught Street entrance mid-week to watch Bohemians train. He was there so often that one of the officials asked him what he was doing. Mick simply told them he wanted to watch and learn because he was a football player and that he already played in goal. On one of these mid-week visits Bohs were short a goalkeeper and the trainer asked Mick to fill in and he obviously impressed enough that he was asked if he wanted to join the club.

By this stage however, his GAA career was over. Displeased by the Associations attitude towards his playing soccer he focused his sole sporting attentions on the “garrison game”. Even years later Morgan refused to attend GAA matches and carried a certain resentment towards the organisation due to its attitude.

Morgan had joined Bohemians at a time of success, they were league Champions for the 1929-30 season and secure as first choice keeper was Captain Harry Cannon. Like his young understudy Cannon had also started out as a GAA man, being a talented Gaelic footballer and hurler, however, like Morgan that side of his sporting life came to an end when he joined Bohemians in 1924. Due to Cannon’s prominence Morgan was confined to appearances for the Bohemian “B” selection who competed in the Leinster Senior League and also appeared in competitions like the Metropolitan Cup. Bohs were victorious in that season’s Metropolitan Cup, beating Dolphin in the final 2-0 with Mick Morgan between the sticks.

Harry Cannon in action for Bohemian F.C.

Morgan was in good company in that side, featuring alongside the likes of Paddy Andrews (a future Irish international), Christy “Dicky” Giles (father of Irish football legend Johnny Giles), as well as veteran Ireland and Bohemians player Jack McCarthy. During the 1930-31 season the Bohs “B” side also finished runners-up in the Leinster Senior League division one with Mick Morgan as their regular keeper. This good form meant that in December 1930 he was given the chance to keep goal for the Bohs first XI in a league match against Dundalk. The reason this opportunity presented itself was the death of Harry Cannon’s father, Thomas, a carpenter, at the age of 64, a few days before the game. As a mark of respect to Cannon the flags were flown at half mast and the players wore black armbands.

Morgan performed well in this debut match as Bohs ran out 3-1 winners but it was to be his only appearance that season as Harry Cannon returned swiftly as the undisputed number one. Progress was also slow the following year despite Morgan continuing to impress for the Bohs “B” side who triumphed in the Leinster Senior League and in the Intermediate Cup during the 1931-32 season. However his first team appearances were limited to two games in the League of Ireland Shield, one of which ended in a heavy 5-0 defeat to Cork F.C.

How the Los Angeles Olympics sent Mick Morgan to France

There would however be something of a bonus for Mick Morgan towards the end of the year as he was chosen to be part of the travelling party that went to Paris for a series of friendly matches. By early 1932 Harry Cannon was well into his work in preparation for the Los Angeles Olympics taking place later that summer. Through his involvement with the Army Athletics Association and subsequently the Irish Amateur Boxing Association (IABA) he had demonstrated himself to be an able administrator. By the end of 1931 Cannon had found himself the Secretary of a Irish Olympic committee alongside Henry Brennan (Irish Amateur Swimming Association) as Treasurer and the infamous Eoin O’Duffy, Garda Commissioner, sports enthusiast, and future ally of Francisco Franco, as its President.

Cannon as secretary was heavily involved in the detailed preparation for the Los Angelus games and by June of 1932, as Tom Hunt has noted, Harry Cannon was “given an additional responsibility when he was appointed Chef de Mission of the Irish team. As such, he was effectively the team manager in Los Angeles and brought the experience of a still active competitive sportsman to the post for the only occasion in Irish Olympic history”. The Games were to go down in history as one of Ireland’s most successful with both Bob Tisdall (400 meter hurdles) and Dr. Pat O’Callaghan (Men’s hammer) winning gold on the same day, 1st August 1932.

These commitments prevented Cannon from travelling for the end of season tour to France in May of 1932 and gave Mick Morgan his opportunity to shine. Bohs took part in two scheduled games in France in what was an interesting time for football in that nation. The French league had up until that point been an amateur one but the upcoming 1932-33 season was to be professional with the 20 team league broken into two groups of ten with the winners of each group playing off in a final for the title. The ultimate winners would be Olympique Lillois who have since merged with another club to form Lille OSC that we know today.

In this context it is interesting that two of these newly professional clubs chose to play matches against Bohemians as preparation ahead of that first professional campaign. The two sides in question were Cercle Athlétique de Paris (CA Paris) and Club Français, both of whom used the Stade Buffalo in the suburb of Montrouge, Antony in Paris. The stadium got its somewhat unusual name due to the fact that an early incarnation of the ground had hosted the Wild West shows of Buffalo Bill Cody, and it would be here that Bohs would play both matches.

Both French sides had a certain pedigree, to even be accepted to the inaugural professional Ligue 1 season they had to demonstrate that they could sign at least eight professional players and had to have performed to a certain standard in the previous seasons. CA Paris had been champions in the amateur era in the 1926-27 season while Club Français had been runners up in 1928-29 and also won the 1931 Coupe de France. Both clubs had players of international caliber as well . Lucien Laurent, the inside right for Club Français had appeared for France in the 1930 World Cup and had scored in their win over Mexico in that competition. He had also gotten on the score-sheet when France played England a year later in Paris where the French emerged triumphant by a 5-2 scoreline. His club mate Robert Mercier scored twice in that game and would finish the inaugural professional season of Ligue 1 as its top scorer.

Lucien Laurent

Louis Finot of CA Paris also featured in that surprise, first-ever win over England in 1931. Such was the joy of the players in beating the English after six previous defeats that the French players asked to keep the English jerseys as souvenirs in one of the earliest examples of shirt-swapping in football history. Finot was also highly successful in other sporting fields as a champion sprinter.

The games against the two sides were scheduled back to back for a Sunday and Monday (15th & 16th May) to coincide with the public holiday around the feast day of Pentecost which gave the competition its name, the Tournois de Pentecôte . Mick Morgan, who had never been out of the country had to collect his passport on the 12th May, catch the ferry that same day and then travel by train and boat to Paris arriving with the team on the 14th, a day before the first game.

Michael Morgan’s passport, stamped on the day he arrived in France, 14 May 1932

While this may have been a maiden voyage beyond Irish shores for Mick it was not the first time a Bohs side had traveled abroad. In 1929 Bohemians had journeyed to Belgium to take part in the Aciéries d’Angleur tournament, which also featured Standard Liege and RFC Tilleur. Bohs won both games and the tournament as well as two other friendly matches during that tour and several of the side who took part would also be part of the travelling party to France such as Billy Dennis, Johnny McMahon and Jack McCarthy. In fact McCarthy had already been to Paris as part of the Irish football team that competed in the 1924 Olympics.

It was perhaps not surprising that Bohemians should be invited to tour, the late 20’s and early 30’s was a good period for Bohs results-wise and they may have had a certain prominence after their tour to Belgium in 1929 and other high profile games against English and Scottish sides.

Team photo from the trip to France with Mick Morgan in the centre

The opening game on Sunday 15th was against CA Paris and finished as a comfortable win for Bohemians. Irish internationals Fred Horlacher and Jimmy White scoring either side of a Parisian O.G. There was a clean sheet for Mick Morgan and the rest of the Bohemian XI that day. The following day saw the game against Club Français which presented a tougher test. They were led by player-coach Kaj Andrup, an interesting character, who as a player represented Danish side AB as well as Hamburg SV, and as a coach would also enjoy spells with Amiens, FC Nancy and Strasbourg later in his career. He was still living in France when the Second World War broke out and despite being a Danish citizen quickly joined up with the French army, he was later captured by the Germans, imprisoned, escaped, and went on to continue his fight as part of the French Resistance.

From the match reports that survive it is not clear if Andrup played against Bohs but he would have been on the touchline to see his charges lose out 2-1. A Billy Dennis goal and a Johnny McMahon penalty making the difference on the day. The team that day (likely the same XI as the earlier match) was Mick Morgan; King, Jack McCarthy; Paddy O’Kane, Johnny McMahon, Doherty; Plev Ellis, Billy Dennis, Ebbs, Fred Horlacher and Jimmy White. A crowd of 6,000 spectators watched the game which was played in poor conditions due to heavy downpours of rain. Despite the journalists bemoaning the impact of the weather on the quality of football the reports suggest it was still a fiercely contested game which was full of incident.

Two wins out of two and only a single goal conceded and victory in the Tournois de Pentecote proved to be a good return for Mick Morgan in his first trip outside the country. An even more impressive return when considered that both CA Paris and Club Français were professional clubs and founding members of the first professional season of Ligue 1. CA Paris would finish their group in 5th place in that debut season while Club Français would finish in the bottom three in their group and be relegated to the second tier despite the fact that centre-forward Robert Mercier finished as the league’s top scorer.

Bohemians must have made a favourable enough impression on the French footballing public as the following season, prominent amateur French side, Stade Français (not to be confused with Club Français) traveled to Dublin to take on Bohemians in another friendly match in which Mick Morgan also featured in goal as part of a 1-1 draw.

The Bohemian F.C. and Stade Français players and their partners in formal wear at a celebratory dinner in the Metropole Hotel after their 1-1 draw.

First team action and personal tragedy

That season (1932-33) was the most successful one in terms of appearances and personal achievements for Mick Morgan. Harry Cannon’s role in the organisation of Ireland’s participation in the Olympics meant that this dominated much of his time and gave an opportunity to his young understudy. The Los Angeles Olympics ran from July 30th to August 14th and also around the same time Captain Cannon was elected to the executive board of the Federation Internationale de Boxe Amateur (FIBA), the world governing body of amateur boxing.

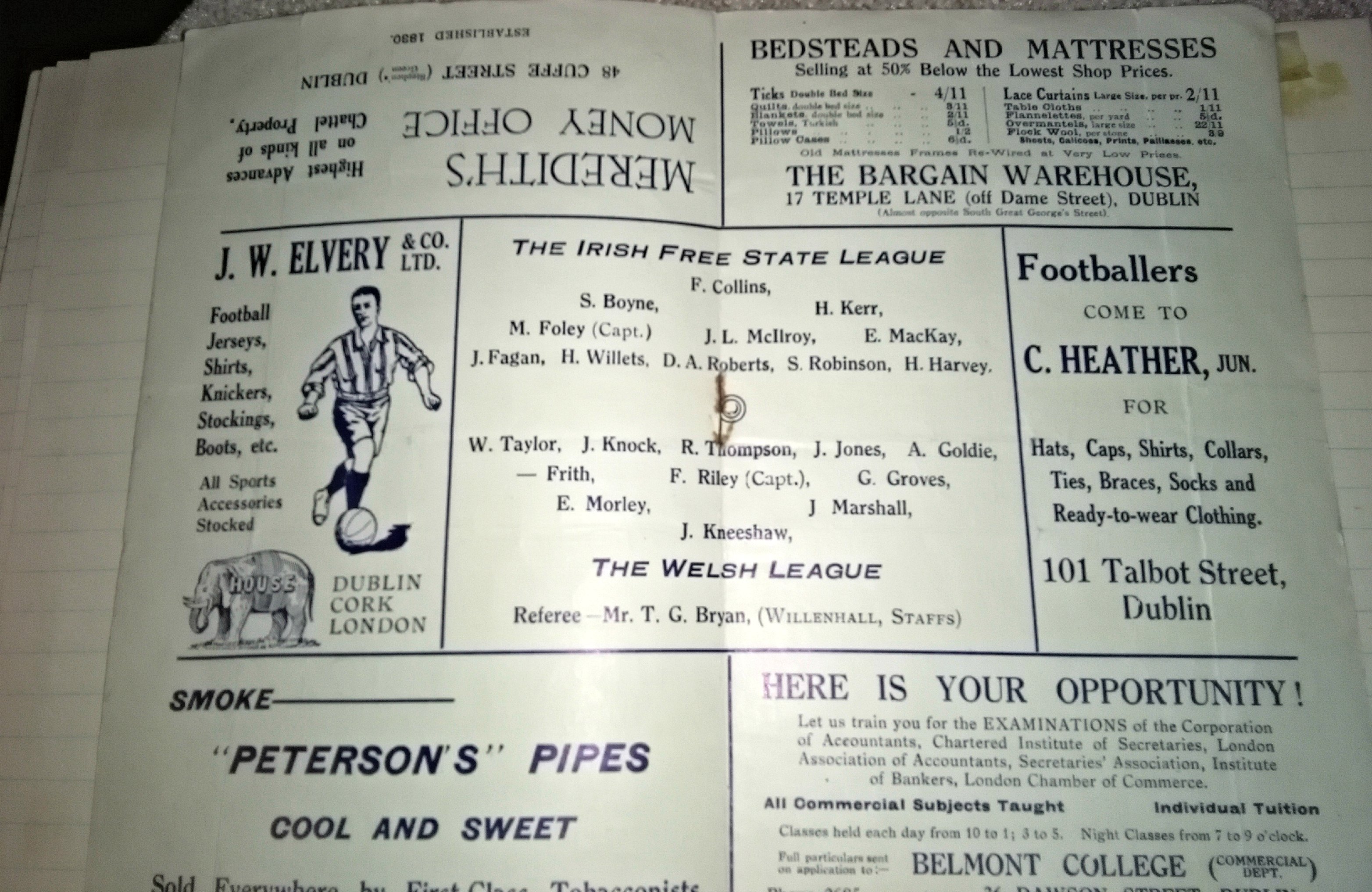

While Cannon’s absence may have gifted Morgan his chance it was his ability that kept him in the team. Over the course of the season Morgan made 31 first team appearances, including starting in 14 out of 18 league games. Cannon, by contrast only made 10 appearances in total after his return from the Olympics. Such was the form of young Morgan that he was even selected to keep goal for the League of Ireland XI in a match against the Welsh League. The Irish Press lauded his selection after a series of “brilliant displays” in the league, they further commented that his “rise to fame is meteoric, as he got his place on the Bohemians team due to the absence of Capt. Cannon who was in Los Angeles when the season opened. Since then Morgan has maintained his place on sheer merit”.

Morgan played with “confidence and skill” and kept a clean sheet against the Welsh League as the League of Ireland notched up a 2-0 victory in Dalymount. Inter-league games were highly prestigious affairs at the time and shouldn’t be viewed as a mere friendly. At the time international matches were far less commonplace and the so-called “Home Nations” were still refusing to play an FAI selection after their split from the IFA. Inter-league matches offered Irish footballers and the sporting public the rare chance to compete against cross-channel opposition. Morgan’s form must have been impressive enough for him to be called up ahead of any other keepers in the league.

While there was inter-league action there was also inner-city action as Mick Morgan was chosen to represent Dublin’s Northside against the Southside in a fundraising match for the construction of Christ the King church in Cabra. Morgan was part of a side that contained other Bohemians players as well as representatives of Drumcondra and somewhat confusingly Bray Unknowns players against a selection from Shamrock Rovers, Shelbourne, Dolphin F.C. and St. James’s Gate. The southsiders would win that game one nil.

One game that did see a return to the side for Harry Cannon was a Shield game early in 1933. Much as the passing off Cannon’s father Thomas had given Morgan his first team opportunity so did the sudden passing of Mick’s mother Mary mean that Cannon was recalled to the Bohs side to face St. James’s Gate. Mary Morgan was only 51 when she passed away, she was described in the language at the time as a woman who “suffered from her nerves” and when her body was spotted floating in the Royal Canal on a cold January day it was presumed that she had taken her own life.

The coroner recorded a death by “asphixiation from immersion in the Royal Canal” on her death certificate. The family history tells that there was some salacious interest in her passing from journalists but such comment never made it to print partially due to the intervention of members of the Bohemian F.C. committee.

Harry’s return and Going Dutch

Despite Mick’s personal playing success and prominence over the course of the 1932-33 season Bohs finished a disappointing 9th out of 10 teams. With the veteran Harry Cannon back for the start of the following year Morgan’s contribution to the first team was greatly diminished. In all Mick Morgan would only make seven first team appearances, all in the Shield or in the Leinster Senior Cup while Cannon starred in the League as Bohs won their fourth title.

The Bohemian squad en route to the Netherlands

While not first choice for Bohs that season there was still the bonus of another end of season tour to the Continent and again Mick Morgan would be first choice. Perhaps this could be viewed as an early example of rotating keepers for European competition? In a later reminiscence in the Irish Independent Mick mentioned that Harry Cannon was “unable to travel” on the tour though the reason wasn’t mentioned.

The destination for this tour was the Netherlands, to compete in the Amsterdam International Tournament along with Go Ahead (now Go Ahead Eagles), Belgian side Cercle Bruges and Ajax. There are some tenuous connections between the sides; former Bohemians striker Dominic Foley ended up at Cercle Bruges in 2009 and helped them to a Belgian Cup final. With Ajax there was an early Bohs link, the first professional manager of Ajax in 1910 was Jack Kirwan an ex Irish international who had lined out for Everton and Tottenham Hotspur where he was part of the 1901 FA Cup winning side.

Kirwan took over an Ajax side in 1910 that were struggling in the 2nd tier of Dutch football but won the second division in his debut season which saw Ajax promoted to the top flight for the first time. It is even said that Kirwan was responsible for choosing the distinctive Ajax strip with its prominent central red stripe so as not to clash with the jersey of Sparta Rotterdam. With the outbreak of war on the horizon Kirwan returned to Dublin in 1914 and later became involved in coaching Bohemians before setting off again to coach Livorno in Italy in the 1920’s.

The trip to Holland wasn’t as successful as previous European outings to Belgium and France. The opening game against Go Ahead took place on 1st April 1934 and Bohs were made to look the fools, losing 6-2 against the side from Deventer. There was however a chance to improve the record the following day when Bohs faced Bruges. A comfortable 4-1 win in front of 13,000 fans in Amsterdam followed, with two goals from Billy Dennis and one each from Ray Rogers and Billy Jordan. In a somewhat unusual format, despite only having won one game each Ajax played Go Ahead in the tournament final with Ajax winning 2-0. Ajax never faced Bohemians in the tournament that they hosted.

The Bohemians team on their tour to the Netherlands

There was one final match as part of Bohs tour, a friendly match in the Hague against a combined XI selected from the city’s clubs. Bohs secured a 1-1 draw with Billy Dennis on the score-sheet for the third game in a row. This game was also a historic moment for Bohemians since it was the first game the club ever played under floodlights. In three games Bohs had a win, a loss and a draw and Mick Morgan had played 90 minutes in every game. That final match against the Hague XI had taken place on April 4th and most of the Bohs team would then have headed back to Dublin although Billy Jordan and Fred Horlacher remained behind on international duty.

The Netherlands had a World Cup qualifying fixture against Ireland in Amsterdam on the 8th of April and Jordan and Horlacher had been selected as part of the squad. Those with a more cynical view might suggest that the invitation to Bohemians was in fact a bit of a scouting exercise by the Dutch? Bohs were league champions and players like Paddy O’Kane, Paddy Andrews, Fred Horlacher and Billy Jordan were all present or future Irish internationals. Indeed Horlacher had featured for Ireland in 1932 against the Netherlands, a game which Ireland had won 2-0.

The Dutch FA certainly weren’t taking any chances this time around though, going so far as to ask the FAI for photos and fact-files on their main players under the premise of using this information for promotional material ahead of the game. The FAI duly obliged, with photos and details of Ireland’s star striker Paddy Moore appearing in Dutch newspapers ahead of the game. The Dutch had good reason to fear Moore, the Aberdeen player had scored four in the previous game, a 4-4 draw with Belgium and was seen as Ireland’s main attacking threat.

In the game against the Dutch Cork City’s Jim “Fox” Foley kept goal, he had just won the FAI Cup with Cork and was about to make a move to Celtic. Among the Bohs men in the squad Billy Jordan started the game but was injured in the first half and was replaced by his club-mate Horlacher just before half-time. This Bohemian for Bohemian swap meant that Horlacher made history by becoming the first substitute used by the FAI in an international match.

With the sides tied at 1-1 Paddy Moore scored a controversial goal just before the hour mark when he pushed the Dutch keeper Adri van Male over the goal line when he had the ball in his hands. This tactic of barging the keeper was not uncommon in Irish or British football at the time and was something that Mick Morgan and Harry Cannon would have encountered regularly but it was not something the amateur Dutch players had experienced before. The goal was awarded much to the dismay of the record crowd of almost 40,000 packed into the Olympic stadium in Amsterdam. Ireland were now 2-1 up with just over half an hour to play. A win would have sent them to their first ever World Cup.

A record Dutch crowd at the 5-2 game in 1934. (source http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl )

But it wasn’t to be. The controversial goal spurred the a talented Dutch side into action, they scored four unanswered goals in 23 minutes to claim a 5-2 victory and qualify for the 1934 World Cup. Ireland would just go home.

For Mick Morgan the trip to Holland would prove to be something of a final hurrah for him at Bohemians. The following season (1934-35) Harry Cannon remained firmly Bohemians’ number 1. Morgan’s only first team appearance was in a 3-2 defeat to Drumcondra in the now-defunct Dublin City Cup. Even at the “B” team level his place was under threat from other keepers like Bill Nolan and Austin Norton.

Later life and career

The following season saw Mick keeping goal for the Bohemian “C” team. Slightly later in 1936 he was also tending goal for the Hospitals’ Trust side in the Leinster Senior League and during their successful run to victory in the Metropolitan Cup in May 1936. Around this time he left Bohemians for good as a player and it seems there may have been slightly more to it than just the lack of first team action.

Mick’s son Michael says that around that time things were a bit tight financially for the family, and to help out Mick was gifted some money. Michael says that this was the result of a collection by some concerned team-mates or perhaps another explanation may have been some money paid by Hospitals’ Trust by way of an appearance fee. Somehow the Bohemian board got wind of this and cancelled Mick’s membership, perhaps seeing this as a breach of the club’s strict adherence to it’s amateur ethos? Either way it was a deeply disappointing way for Mick to end his time as a player with Bohemians.

There was a very brief return to League of Ireland action at the beginning of the 1936-37 season when he signed for Shelbourne, however Mick’s time with Shels was brief to say the least, he played a single game in the Shield as Shels lost 4-1 to Dundalk.

Mick had always previously played as an amateur prior to his spell with Shels, his day job was with CIE. As a fifteen year-old he had apprenticed as a tinsmith with CIE for a period of five years before eventually he ended up as an engineer at the works at the Broadstone depot. He also grew to be a prominent individual within the trade union movement where he became treasurer of the Irish Sheet Metal Workers Union. According to his grandson, yet another Michael, he felt uncomfortable being paid as a semi-professional at Shels and decided such a role wasn’t for him and quickly left the club. In August of 1936 he had also gotten married to Mary Flynn from East Wall and soon afterward Mick and Mary became parents, these changes in life and the greater responsibility due to his position in the union would have also placed greater demands on Mick’s time, perhaps to the detriment of his sporting career?

It wasn’t to be his last involvement with the sport however, he continued to appear for the Hospitals’ Trust in the late 1930’s before lining out for Jacob’s F.C. in the Leinster Senior League. There was a family connection, Mick’s in-laws had previously worked in the Jacob’s factory off Bishop Street and their works team were competing at a good standard. He continued to line out in goal for the Biscuitment until the early 1940’s and on one occasion at least was even selected to represent a Leinster Senior League XI.

Mick Morgan keeping goal for a Leinster Senior League XI in 1940

In later years Mick Morgan also ran the line at League of Ireland matches and was even linesman during some prestige friendly matches, such as the occasion in 1952 when a Bohemians XI took on Glasgow Celtic in Dalymount Park. When asked by his son what was favourite memory from his time in football, he recalled not his trips to France or the Netherlands but rather the occasion when he saved a penalty taken by Shamrock Rovers defender and Irish international William “Sacky” Glen. That precious type of moment when the ‘keeper stands apart from others and can bask in rare glory.

In his personal life Mick and Mary moved to Drimnagh shortly after their wedding (perhaps another reason for representing Jacob’s?) but couldn’t settle in the newly built, south-side suburb, and then moved back to the northside settling in St. Eithne Road in Cabra, staying in close proximity to Mick’s beloved Dalymount. Whatever the nature of his departure, from the club he had remained good friends with several of his former Bohs team-mates, especially the likes of Billy Dennis and Plev Ellis with whom he had surely whiled away hours of boredom on those boat crossings to the Continent. Mick maintained a keen interest in football generally and Bohemians in particular, he regularly attended matches in Dalymount (standing on the Connaught Street side where he had watched Bohs train as an aspiring goalkeeper) and introduced his grandson Michael to the club as a boy. The younger Michael followed in his grandfather’s footsteps lining out as a goalkeeper for the likes of Home Farm and Tolka Rovers, he also remains a Bohs supporter to this day and was the source for much of the information and excellent photos in this article.

Mick Morgan passed away suddenly in 1979 aged just 69. In a relatively short life he had seen and achieved a great deal. His life was buffeted by the ebbs and flows of wider social change, as a young child his family had been directly affected by the deprivations caused by the 1913 lock-out, had this perhaps informed Mick’s later career for the state-owned CIE and his own activism as a trade union official?

He had encountered first-hand the sporting exclusion of the GAA “ban” as a teenage hurler in the early years of the State, an experience which soured him towards Gaelic Games but perhaps ensured his focus remained on football. It was through football that he had opportunities to travel that were not afforded to many young men of his generation, to play in France and the Netherlands with and against players of international calibre in front of tens of thousands. Even under floodlights decades before the Dalymount pylons would help define the Dublin skyline. Though in all he made barely fifty first team appearances for Bohemians it is through this small sporting prism that we can view a life lived during decades of upheaval in a period that straddles the foundation of the State, exposing the issues of nationalism, worker’s rights and the day to day challenges that ordinary people faced when times were tough and life was too often cut short.

Mick’s story is one that opens a window into the life of an ordinary man in the Dublin of the 20’s and 30’s but one who had little bit more of a Bohemian, unconventional life.

With special thanks to Michael Kielty and his family for sharing their stories, photos and memories of Mick Morgan and as is often the case to Bohemian F.C. historian Stephen Burke.

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory