Wonder, death and rebirth – Austria Vienna in the 1930s

A simple photograph of four teammates, stars for club and country, in their homeland they are viewed as part of a footballing golden age, central to the rise of one of the strongest national teams in Europe. For their club they regularly challenged for trophies and beat the best that Europe had to offer. The photo shows the men in the jersey of the Austrian national team rather than their club FK Austria Vienna. It is taken around the early to mid-1930s with the players wearing thick white jerseys with lace-up collars, their hair slicked and brushed back in the style of the time. They look confident, at ease, a hint of a smile plays on more than one of their faces. By the end of that decade two of those men would be dead, one under mysterious circumstances that still provokes discussion to this day, and the other two? One would have to flee the newly arrived forces of Nazi Germany and escape the country with his Jewish wife, partly as a result of the actions of the man standing next to him; a committed fascist who helped overthrow the management of Austria Vienna. This is an attempt to tell the story of these four men – Matthias Sindelar, Karl Gall, Hans Mock and Walter Nausch and that of the club Austria Vienna, in their journey from triumph to tragedy in the 1930s.

In 1936 an Austrian side dubbed, the Wunderteam beat England 2-1 in Vienna. It was only the second time ever that the English had been beaten by Continental opposition after a defeat to Spain some seven years earlier. This was a special side, one born out of a vibrant and developing footballing culture. The Austrians were among the most progressive footballing nations in Continental Europe. Their league centred around the capital city of Vienna was the first on the Continent to go professional in 1924 and only a few years later the visionary Austrian coach and administrator Hugo Meisl helped create the Mitropa Cup or Central European Cup. This was one of the first international club tournaments and it began in 1927 and featured two top professional teams from Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, and later teams from Italy, Switzerland and Romania would enter as the tournament expanded.

By the 1930s the Austrians were a major force in European football, in 1931 they trounced Scotland 5-0 in Vienna, that result was sandwiched between a 0-0 draw with England (also in Vienna in 1930) before an unlucky 4-3 defeat to them in Stamford Bridge in 1932. And it wasn’t just the hapless Scots who the Austrians were racking up the goals against. Right after that win against Scotland the Austrians put six past the German national team in Berlin and five in the return fixture in Vienna. The following months would see them put eight past Switzerland in Basel and another eight past Hungary in Vienna. In 1932 and 1933 there were wins over Italy, Sweden, France and Belgium (twice) and the Netherlands as the Austrians geared up for the 1934 World Cup.

In qualification Austria had been drawn in a group with Hungary and Bulgaria but only had to play a single game, dispatching the Bulgarians with ease 6-1. Bulgaria had also suffered two defeats against Hungary and withdrew from qualifying which guaranteed Austria a spot in the World Cup in Italy after just a single game.

The 1934 tournament ran on a simple knock-out cup format without any group stages. Austria were drawn in the first round against France. Now, the Austrians had comfortably beaten the French 4-0 just a year earlier but faced a different proposition in the opening game of the World Cup. The French looked to curb the influence of the Austrians, centre-forward, talisman and playmaker Matthias Sindelar by man-marking him with their half-back Georges Verriest. Though Sindelar opened the scoring in the Stadio Benito Mussolini in Turin, it was a much tighter game and Austria only prevailed 3-2 after the French had taken the game into extra-time.

Austria defeated neighbours Hungary in the quarter finals by a margin of 2-1 in a bad-tempered game and were drawn against hosts Italy in the semi-finals. The hosts won the match 1-0 thanks to a controversial first-half goal in the San Siro. For the 3rd place play-off the Austrians made numerous changes, which included dropping Sindelar and having to wear a borrowed set of blue Napoli jerseys as their white and black kit clashed with their opponents Germany. Despite high-scoring wins over the Germans in the previous years it was the Austrians’ larger neighbours who would prevail. Austria seemed cocky with full-back Karl Sesta (sometimes written as Szestak) taunting German attacker Edmund Conen by sitting on the ball when Conen tried to dispossess him. On the second occasion he did this Conen managed to dispossess him and scored a vital goal. Sesta did make some amends in the second half by scoring himself but it was not enough, the Germans had won 3-2.

Of the squad that went to Italy for the World Cup three players were on the books of FK Austria Vienna; forward Rudolf Viertl, the young, skilful attacker Josef “Pepi” Stroh, and the team’s star, Matthias Sindelar, while directly after the World Cup they were joined by Karl Sesta who moved from Wiener AC.

Two years later when that famous win against England rolled around the contingent of FK Austria Vienna players had risen; Sindelar started against England at centre-forward, with Viertl at outside left, young Stroh played at inside-right while the team was captained by Walter Nausch another Austria Vienna player. Two more players from the club featured, Johann (Hans) Mock at centre-half and Karl Sesta at right-back while it was Viertl that opened the scoring in the 2-1 win for the Austrians.

The high concentration of players from Austria Vienna was not to be unexpected, the club were enjoying one of their most successful periods, winning the Austrian Cup in the 1934-35 and 1935-36 seasons and would finish runners-up in the league in 1936-37. During the 30s they also won two Mitropa Cups in 1933 and again in 1936 with final wins over Inter Milan (then styled as Ambrosiana after St. Ambrose of Milan, the Italian fascists deemed their original name too “international”) and Sparta Prague respectively. They had a genuine claim to be one of the strongest club sides on central Europe. While the second leg of the 1933 final has gone down in history as one of the finest ever performances by Mattias Sindelar – with Austria Vienna trailing 2-1 from the first leg he scored a hat-trick of spectacular quality to win the match 3-1 and secure the trophy would return with him to Vienna.

However, one cannot write about the FK Austria Vienna team of this era and ignore what came next. 1936 had seen them win both the Austrian Cup and Mitropa Cup and supply numerous players to the Austrian National team, but less than two years later there would not be an Austrian national team, and there very nearly was not an Austria Vienna at all. The Anschluss, the effective annexation of Austria into a greater Germany ruled by Adolf Hitler took place in March 1938. This was an especially dangerous time for Austria Vienna as they were viewed as a “Jewish club” and featured many members of the city’s large Jewish community among their players, board and fans. The club’s first president, Erwin Müller was Jewish, as was their president at the time of the Anschluss, Emanuel “Michl” Schwarz.

The club faced huge upheaval after March 1938, they were initially suspended for not being under “Ayrian management” until a former amateur player, and leading member of the local SA (Sturmabteilung, commonly known as the Brownshirts), Hermann Haldenwang was installed as the new head of the club. He arrived at the club in full SA uniform, accompanied by first team player Hans Mock, who was similarly attired. Haldenwang wanted to change the club’s name to SC Ostmark as the use of the name Austria was considered too nationalistic. Jewish players and officials were no longer allowed at the club, and the clubs stadium was taken over by the German army for training purposes.

By the summer Haldenwang had been transferred and the club were unique in being able to return to the use of their former name. By this stage most of their board and many of their players had fled. Emanuel Schwarz initially hoped that he would be protected by virtue of his “mixed marriage” to a non-Jewish woman and he stayed in Vienna and waited for a visa for the United States. Ultimately, he was forced to divorce to try and protect his wife and son. When his visa failed to materialise, he decided to flee, first to Bologna, which he managed through his contact Giovanni Mauro within the Italian FA. And then with the support of FIFA President Jules Rimet, he obtained an entry permit for France in 1939, where he was forced into hiding after the German invasion. In 1945 at the War’s end he was reinstated as Chairman with the club recognising him as their only legitimate leader stating that the role remained his despite his absence.

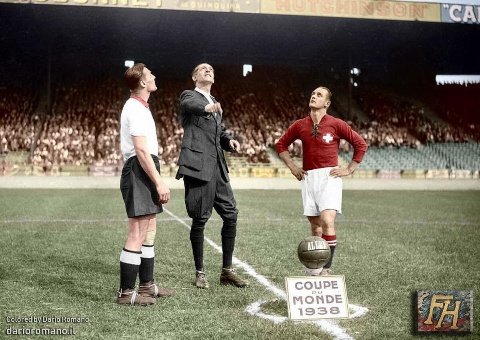

Hans Mock who had effectively helped to oust Schwarz, had been an Austrian international, however with no Austria in existence to compete at the 1938 World Cup he was representing a newly enlarged Germany at the competition. He had been a member of the SA even when the organisation was illegal in an independent Austria, he surely was happy to get the chance to represent the Reich. He even got the opportunity to captain Germany in their opening game at World Cup against Switzerland. The match finished a 1-1 draw and Mock was dropped for the replay which the Swiss won, eliminating Germany in the first round. Mock would continue at Austria Vienna until 1942, playing his last game for them at the age of 36. Mock survived the War and after dabbling in coaching ran a wine bar in Vienna until his death in 1982 aged 76.

Hans Mock captains Germany v Switzerland at the 1938 World Cup photo

While Mock may appear an obvious villain of the piece, selling out teammates and club members he must have known would have to be removed from the club and likely flee the country, the decisions made by other Austria Vienna players less obviously sympathetic to the new regime bare further scrutiny. One result of the Anschluss was that all sport was to return to being notionally amateur, thus at a stroke the entire professional playing staff of Austria Vienna was out of a job. While some had trades to fall back on others sought to leave the club for other professional leagues, notably the French league, while still others tried their hands at new business ventures.

By the time of the Anschluss Austria’s star footballer Sindelar was already 35 and increasingly injuries were taking their toll on him, by 1938 he was featuring less-regularly for Austria Vienna and when he did play he was pushed out to the right wing and not afforded as central an attacking role. He decided to follow a route well-trodden for footballers coming to the end of their careers and go into the hospitality business, running his own café, the Annahof Coffee House in the district of Favouriten, somewhere that Sindelar knew well in his local neighbourhood. Most reports note that Sindelar got a café at an attractive price as it was owned by a man named Leopold Drill, because Drill was Jewish he was no longer permitted to own a business and was forced to sell. Sindelar, an ageing footballer coming to the end of a career for which he could no longer legally be paid was the clear beneficiary of this transaction.

Sindelar was not alone in this, his teammate Karl Sesta similarly bought a Jewish owned bakery and it took until 1953 for the bakery’s rightful owner, Josef Brand to get the business returned to him. While Sesta survived the War and continued playing until 1946, earning a living from the bakery throughout, Sindelar did not get to benefit from ownership of the café for long. One night after drinking with friends in January 1939 Sindelar left to go to the apartment of his girlfriend Camilla Castagnola, it was the last time he was seen alive. Friends worried about Sindelar the next day broke down the door to Castagnola’s apartment to find her unconscious on the bed with Sindelar already dead beside her. Castagnola would later die in hospital and both deaths were judged to have been as a result of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Despite this judgement theories abounded that Sindelar had been killed by the Nazis, with various reasons put forward to justify this suspicion: Sinderlar’s supposed Social Democratic leanings (despite his calling for Austrians to ratify the Anschluss in a referendum), his refusal to play for a Greater Germany side, supposed Jewish heritage either in Sindelar’s family or in that of Castagnola. Even today many still point to these theories and as a result for many, Sindelar has been cast as a symbol of resistance to Nazi rule. While his personal life and legacy remain complex his role at the heart of one of the greatest players in Austrian history remains more safely uncontested.

The death of Sindelar’s teammate Karl Gall was more brutally straightforward, the skillful winger had 11 international caps to his name. He had spent three years playing in France for Mulhouse until the outbreak of War had prompted his return to Austria Vienna in 1939. By 1942 he was still playing at the age of 37 when he was conscripted into the Wehrmacht and sent to the Eastern front. On February 27th 1943, in the harshness of the Russian winter a landmine tore apart one of the most elegant players ever to represent Austria Vienna.

He was not the only member of Austria Vienna to die violently during the War years. Josef Adelbrecht, like Gall, died on the Eastern Front, while a young player named Franz Riegler died in an air-raid on Vienna. Robert Lang, an early player, then later coach and board member of the club fled after the Anschluss, first to Switzerland and later to Yugoslavia, rightly fearing for his safety as a Viennese Jew. He continued coaching, but after Belgrade fell to the Nazis in 1941 he was imprisoned and murdered.

The final member of our foursome was Walter Nausch. A talented, cerebral midfielder, Nausch was a born leader, he had been a captain of Austria Vienna and key to many of their successes. While Nausch was not Jewish, his wife was, and he was “advised” that he should seek a divorce. Rather than do so Nausch and his wife fled across the border to neutral Switzerland where he began his coaching career. After the War Nausch was able to return to Vienna and in 1948 he became national team coach of Austria. In 1954, some twenty years after being part of the Wunderteam that reached the semi-finals Nausch was able to lead the Austrians to another World Cup semi-final, while they lost heavily against eventual winners West Germany they would do slightly better than Italy 1934 by beating the Uruguayans 3-1 in the third place play-off. It remains Austria’s best-ever World Cup performance.

With special thanks to Clemens Zavarsky for his assistance. A version of this article appeared in issue 3 of View Magazine.