Welcome to the “super league”

In a simpler time European football was full of international club competitions that were outside of the purview of UEFA or FIFA. Sometimes these competitions lasted decades, other times they fell into abeyance after a single outing. The clubs entering changed, as did the scope of the competitions. Travel and touring were more onerous committments so the international tour was a real endeavour and there was often fear that undertaking such journeys could lose a club a lot of money.

One such tour took place in 1954 when Honvéd FC, the Army team of Budapest visited England to play against Wolverhamption Wanderers. Both clubs were national champions and the game was played on a Monday, under lights and the match was broadcast on BBC television as Wolves defeated Honvéd 3-2 in an exciting game, though they did water the pitch at half time to disrupt the Hungarians style of play.

This result salvaged a bit of pride for the English after the Hungarians had defeated their National team a year earlier and they responded in understated fashion with Wolves manager Stan Cullis and many sections of the British press declaring Wolves to be “champions of the world”. In France the former footballer Gabriel Hanot, by then working as a journalist for L’Équipe, saw the ridiculousness of this statement. European club football’s greatest side could not be decided by a one-off game in a non-neutral location. He devised the format for the European Cup and brought it to UEFA, telling the governing body that if they did not create the competition, then his magazine would. In part, due to a reaction to English arrogance and self-imortance the European Cup was born.

The successors of Wolves as English Champions, Chelsea, were invited to take part in the inaugural European Cup tournament. They declined on the invitation after the intervention of Football League secretary Alan Hardaker, a true little Englander who derided European football as being full of “wops and dagoes”. Hibs, who had finished the previous season in Scotland in 5th place became the first British team to enter the competition, they reached the semi-finals.

But from such humble beginnings eventually grew the UEFA Champions League, though for much of the existence of the European Cup the tournament could end up costing a club money rather than making it for them. It truly was about competition and prestige. Sometimes this prestige was usurped by the various dictatorships that existed in Europe at the time, but it was as Danny Blanchflower put it, about the Glory – as he memorably said;

The great fallacy is that the game is first and last about winning. It is nothing of the kind. The game is about glory, it is about doing things in style and with a flourish, about going out and beating the lot, not waiting for them to die of boredom

Danny Blanchflower

There is glory in competing in a gruelling competiton against the best the Contintent has to offer and being crowned Champions. Even better if like Real Madrid of the 1950s, Ajax of the 1970s or AC Milan of the 1990s you can do it with a flourish. But to be clear there can be no Glory in any “super league” because it is objectively not about the best, it is not even about the richest, (though these breakaway clubs aim for this) it is about those with the greatest greed and ego who cannot allow their own rash decisions, mismanagement and avarice get in the way of them “winning”.

Football grew in popularity to become the dominant sport in the world not because the brand, or the tournament, or the stadium or the kit or all the other layers of ephemera that make up the modern game, but because it was simple and easy to play and provided something that humanity craves, competition. It was why it became a game beloved both of factory workers and elite school headmasters who thought they were moulding the future of empire. Strip it all back and even before there were crowds paying to stand on the edge of a pitch there was the thrill of playing, or winning or losing, of glory and magnamimity, of sating that competitive impulse in all of us.

Most of us, before we have entered a stadium or even watch a full game on television have kicked a ball with friends in a park or garden and felt that little rush. This is the basic and fundamental purpose of football, whether playing, or as a spectator supporting our team. With a closed shop super league – a disfunctional plutocracy of the bloated elite – we lose the thrill of competition. Yes someone might win in their sanitised league but there are no real consequences, lesser clubs might be allowed to partake on occasional but the “founders” are untouchable, no matter how badly run they are. There is no glory here.

Incidentally, Danny Blanchflower who made that quote about Glory was the last man to captain Tottenham Hotspur to a League title. Sixty years ago. Super indeed.

Of course, many can argue that this is just natural progression, or that football had lost its soul years ago. And there is truth to this, I stopped taking anything more than a passing interest in the English Premier League years ago partly for the reasons of the increased greed and corporatisation of the game, but this is still worse. We can be critical of existing, deeply imperfect structures, while acknowleding this is worse. We are in the invidious position of being on the side of UEFA and FIFA afterall.

And while the Premier League was about the greed of the Big Six (poor Everton) who had spotted the money to be made through TV rights licencing, the move to separate the “Premier League” at least made a certain sense in the context of the early 1990s. English football was emerging from the ban on European football for its clubs post-Heysel, it had witnessed the horror of Hillsborough and the contempt of the Thatcher government for the sport. The new Premier League even cherry-picked much of the post-Hillsborough Taylor report (ingoring the parts about keeping match tickets affordable for the average fan obviously) and presented this new league as part of a reform agenda in the game. Most importantly it was still part of a wider structure, it remained like the old First Division as part of a wider football pyramid with promotion and relegation. Manchester United were still owned by the likes of the Edwards family who ran a chain of Manchester butcher’s shops. The most controversial owner was someone like evil-Santa lookalike Ken Bates at Chelsea who had spent most of their time back and forth between the first and second tiers over the previous decade.

These men were still somewhat typical of the people who ran football clubs in Britain, and elsewhere – successful, often egotistical, occasionally despotic local businessmen who invested in clubs out of mix of genuine passion, vanity and desire for public profile. Mostly the old maxim held true was that the fastest way to have £1 million was to start with £10 million and get on the board of a football club. That began to change in the 1990s though, in 1998 the Football Association got rid of Rule 34 which “prohibited directors from being paid, restricted the dividends to shareholders, and protected grounds from asset-stripping.”

With growing TV revenue it was now possible to make real money from football and not squander it. For the first time rich people could invest in football and hope to get Richer! This wasn’t just in Britain, in Spain, clubs which were once practically all member owner had to become limited companies in the early 1990s. Only Real Madrid, Barcelona, Osasuna and Athletic Bilbao remain in member ownership now.

As we can see with Barcelona and Real Madrid, despite being the biggest teams in Spain, despite having huge historic European success, and a disproportionate share of domestic TV revenue, both clubs are massively in debt. Their combined debts are over €2bn and it is arguable that if they were anything other than hugely popular football clubs they would have been liquidated. Their debt alone would eat up over a third of $6bn that J.P. Morgan are reportedly providing to back the breakaway league. Both clubs also have ambitious stadium redevelopment plans which will cost 100s of millions. No doubt the super league will be presented to the members who elect men like Florentino Pérez as necessary to the survival of these, incredibly poorly run, badly managed, debt-ridden institutions.

Of course, that is something that J.P. Morgan know all about, Jamie Dimon, their billionaire chair and CEO was at the helm when the bank received a $26bn government bailout in 2008 because of the massive losses they accrued due to their reckless lending practices.

Barca and Real aren’t alone in being horribly indebted and badly run, Inter Milan, (debt at €630m the largest in Serie A) are in turmoil due to uncertainty about the future involvement of its parent company Suning Appliance Group who decided to shut down a soccer club in its hometown of Jiangsu, China and raised concerns that the next to get entangled in the indebted company’s efforts to raise cash could be its prize asset in Italy.

These clubs aren’t the best either on the field, or on the spreadsheet but they hope that the sheer hype of the new league will be enough to sell TV subscriptions and eventually sell match tickets and merchandise. The rationale for all this according to men like Pérez and Andrea Agnelli (and the various American investors who want a franchise model) is that they are giving the “fans” what they want. That at a time when the major five European leagues have never been more sewn up by the bigger clubs, they decided that a club like Leicester winning a title was a “bad” thing for football. These “fans” would rather see a plodding post Wegner Arsenal than Leicester in Europe I suppose? Because… who the fuck knows, they have more social media followers and generate more tedious twitter disputes? This is of course poor little, owned-by-billionaires, Financial Fair Play breaching, plucky underdog Leicester, who had the misfortune of not being bought by the right oligarch or sovereign wealth fund, or at least not being bought at the right time.

As it’s my blog and I can indulge in an old man rant here are a few things I can clearly recall in my 30-odd years. They include Manchester City fighting for promotion with Gillingham and relying on Shaun Goater rather than Sergio Aguero for goals, Athletico Madrid being relegated, Juventus being relegated for their massive corruption (how would the super league deal with this? Where would you relegate them to?) Chelsea being a yo-yo club whose record signing was Paul Furlong. Spurs constantly being Spurs.

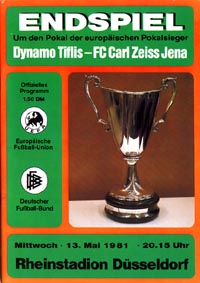

Juventus have the same number of European Cups as Nottingham Forest – who to their credit never celebrated winning a title while their fans lay dead in the stadium corridors. Most of those involved have less European titles that say a club like Ajax – four time European Cup winners who have given more to the development of the European game than most, no Benfica or FC Porto mentioned? What of the German heavyweights – in a nation where most clubs remain majority fan-owned and crippling debts are not a concern for Dortmund of Bayern Munich will a super league get the blessing of a politically engaged fan culture?

Also didn’t you like the nod to women’s football? As Suzy Wrack of the Guardian points out this is even more embarrassing that the men’s breakaway league, Liverpool’s women’s team is currently in the Championship after being relegated a couple of seasons ago. Juventus have had a women’s team for four years, Manchester United for three years, AC Milan for two years and Real Madrid? They bought CD TACÓN last year and rebranded them as Real Madrid. Of course no inclusion of Lyon who have only won the Champions League seven times.

So what next? If the “founding 12” do really decide to split then leave them to it, but really leave them, salt the earth of Carthage, refuse them water, fire and shelter. expel them from all domestic competitions, ban all players from playing for their national teams, no World Cup, no Euros, remove all players and teams from FIFA video games or other promotional products. English sides in the “super league” should not be able to avail or the already punitive transfer arrangements in place for the signing of young players from lower league clubs. If Governments have the guts they will see this as bad for the game in their respective nations and will offer concrete resistance and not just verbal condemnation. No more public land, or grants for new or redeveloped stadiums would help.

In closing fuck the so called super league and I hope to see you in Dalymount when next we can dance.