Who was Albert Straka, the penalty king of Sligo?

Hundreds, maybe even thousands of the record crowd had flooded onto the pitch, reports said that there were six, maybe seven thousand packed into Showgrounds. The English referee, brought from Sheffield to the west coast of Ireland to take charge of a first round FAI Cup tie, had trouble restoring order. It was unclear to some why J.E. Bennison had blown his whistle in the first place, a penalty had been awarded for a foul on a Sligo Rovers player but thousands of heads straining for a view from amid the multitude weren’t sure exactly what had happened. Sligo were trailing 2-1 in the dying moments of the match to Shamrock Rovers, and already struggling in the League, the chance of a Cup run was all that was left of Sligo’s season. A last minute penalty, a lifeline, the dreams of Cup glory might live for another day.

But first, the decisive kick had to be taken. Bennison had made it clear that the penalty kick was to be the last kick of the match, miss and Sligo were out, score and a replay was secured. It took twelve minutes to clear the crowds that had swarmed onto the pitch, dozens still encroached on the playing surface but enough space had been cleared to allow a clear sight of the goal and Shamrock Rovers netminder Charlie O’Callaghan. A ring of players from both sides was formed around the man approaching the penalty spot, around them another ring of the “suddenly hushed spectators”, Albert Straka placed the ball on the spot, calmly ran up and dispatched the it into the corner of the net, Sligo Rovers would live to fight another day.

Three days later, thanks to goals from Paddy Coad and Liam Touhy, Shamrock Rovers won the replay 2-1 and would go on to lift the cup that year, defeating Drumcondra in the final. Despite this ultimate outcome the “Straka penalty” has entered Sligo Rovers history, it is included in a panel at the club’s outdoor museum at the Showgrounds and is still recalled in media pieces almost seventy years after the fact. But who was Albert Straka? Signed by Sligo Rovers in February 1955 as a player-coach with the club languishing at the bottom of the League, his time in the north-west was brief and he was released by the time the season had concluded at the end of April, his penalty in the Cup game and the chaos that surrounds it were probably his most lasting legacy from his short time in Ireland.

Straka, according to the limited biographical information furnished after his signing, was from Vienna, Austria, spoke very little English, was thirty-two years of age, 5’9″ tall, of stocky build and had previously played as a forward with well established Austrian clubs like Simmeringer SC, Admira Vienna and Floridsdorfer AC. It was further stated that Straka had once been a teammate of Austrian captain Ernst Ocwirk, probably Austria’s most famous footballer at the time and known to Irish soccer supporters having played in Dalymount Park in an international against Ireland two years earlier. Ocwirk has been at Floridsdorf as a young player before moving to Austia Vienna in 1947. Straka however, had listed his most recent club as FK Pottendorf, a club based fourteen miles south of Vienna.

Now, while the small town of Pottendorf is indeed south of Vienna, their football club was not as the Irish Independent stated, sitting fourth in the Austrian League, any team with Pottendorf in their name were playing in the amateur leagues in Austria. In fact, the Austrian football writer Richard Turkowitsch confirmed that SVg Pottendorf were a third division club at the time (Landesliga Niederösterreich to be precise), so at the time of his transfer Straka had been playing in a regional league. It is also interesting to note that while Austria had allowed professional football as early as 1924 in several newspaper reports it is noted that Albert Straka was a barber rathen than footballer by profession.

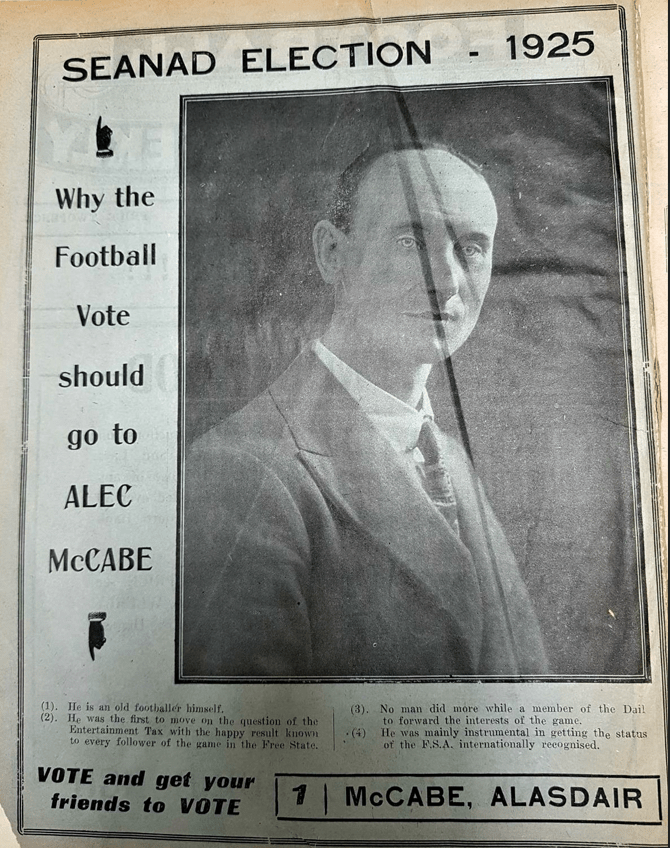

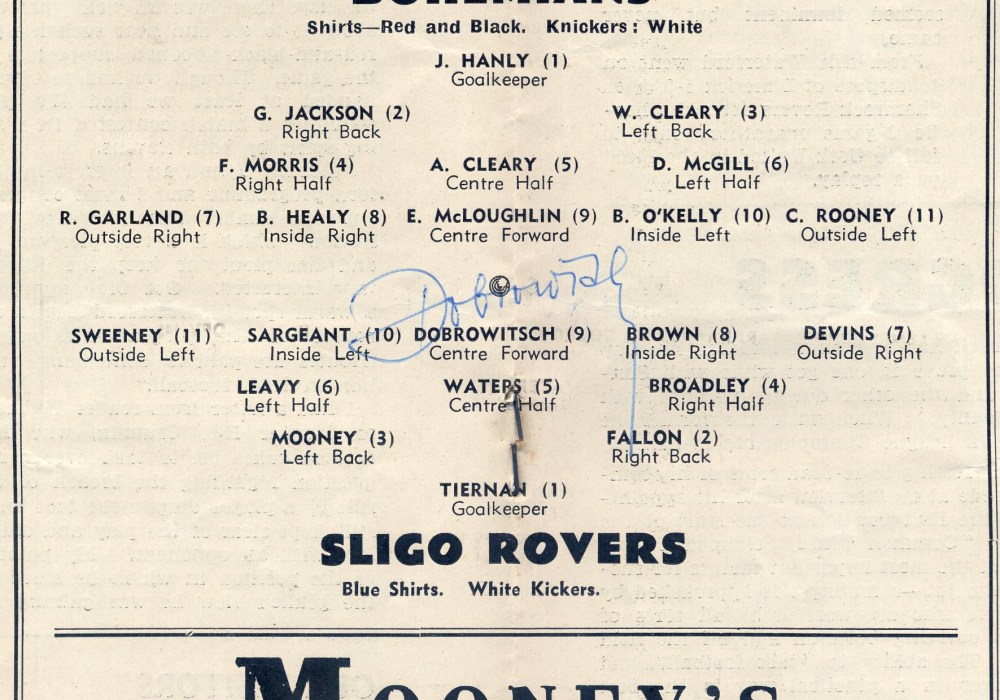

It is in more recent publications that Albert Straka is listed as having been an Austrian international, no such claim seems to have been made at the time, but it was stated that along with being a former teammate of Ernst Ocwirk and having played with prominent Austrian clubs, that he had also been on European tours with his clubs to nations such as France, Norway and Sweden. The statement that a small town amateur team like Pottendorf were fourth in the Austrian league sounds like it could have been a significant exagerration on behalf of Albert. I’ve written previously about how Sligo had signed Siegfried Dobrowitsch, a supposed Hungarian international in 1949, who was most likely a lower league Hungarian player who had never been anywhere close to the Hungarian national team. Both the signing of Dobrowitsch and Straka were organised through Alec McCabe.

McCabe is an interesting and controversial character in his own right. A Republican revolutionary, he was a member of the Irish Volunteers and later the IRB, he met with Seán McDermott, Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke and James Connolly immediately prior to the Easter Rising of 1916 and tried unsuccessfully to ignite an uprising in County Sligo at the time to little effect. Interned in the Rath camp in Kildare during the War of Independence he was a TD in the fourth Dáil for Cumann na nGaedheal, resigning his seat after the failed Army Mutiny of 1924. McCabe, was a teacher by profession and a founder member of the Educational Building Society (EBS). As the 1930s progressed he became more involved with the Blueshirt movement and with the Irish Christian Front at the outreak of the Spanish Civil War. At a large public meeting in College Green in 1936 McCabe spoke to the crowd about the dangers posed by Communism and praised the efforts of Dictators in other European nations in fighting its spread, stating of the perceived Communist threat “thanks to Hitler, they [Communists] were crushed for all time in Germany, and, thanks to Mussolini, they had been checked in Italy. Thanks to Franco, they would never come to Ireland.“

McCabe was briefly interned in 1940–41 “because of his pro-German sympathies” however on release he returned to teaching and his work with the EBS, eventually becoming its full-time managing director, a position he held until 1970. His interests also clearly extended to sport, in his youth he was an accomplised Gaelic, soccer and rugby player and after hanging up his boots he remained very active in various roles with both Sligo Rovers and the FAI. In relation to Straka he was referred in the Sligo Champion as the key organiser of the signing and was described as Sligo’s “representative in Dublin” as due to his role with the EBS he was by then, permanently living in Ranelagh.

McCabe seems to have had several connections in Continental Europe, perhaps through various roles at the FAI. There are newspaper reports of him providing Irish journalists with hard to find European sports publications as well as the fact that he somehow found a network that allowed him to sign Straka and back in 1949 Siegfried Dobrowitsch, a former WWII soldier in the Hungarian army for the Axis powers who later claimed to have fled Hungary after the rise of Communism and found his way to Ireland via a spell in France. Speaking later in 1955 at the end of season AGM the Sligo Rovers secretary Charlie Courtney said that Straka had been “highly recommended” to Alec McCabe by an unnamed party, and that McCabe “at no small expense and inconvenience to himself obtained Straka’s services” which confirms that there was at least some sort of informal football network who viewed McCabe as someone likely to take a risk on a European player.

Straka put pen to paper just before the first round draw of the FAI Cup, Sligo were at the time bottom of the League and as mentioned were hoping for a Cup run, boosted by a high profile signing to give some meaning to their season and increase gate receipts at the Showgrounds. It was a path Sligo had travelled before, signing Dobrowitsch in 1949 and most famously signing ‘Dixie’ Dean in 1939 where he enjoyed a brief and prolific spell propelling Sligo all the way to the final of the FAI Cup while drawing massive crowds everywhere he played during his Irish sojourn.

This practice of course wasn’t just limited to Sligo Rovers, Cork Athletic had pulled off something of a coup in 1953 by bringing in a 39 year old Raich Carter. Carter, one of the standout creative attacking talents of the 30s and 40s who still possessed enough of his footballing gifts to make a major impression on the League of Ireland and help Cork Athletic to Cup victory over city rivals Evergreen United. The same week that Albert Straka signed for Sligo Rovers another veteran English forward was signed by Shelbourne, Frank Broome had been a star for Aston Villa and Derby County during the 30s and 40s and Shels hoped the former England international still had enough in his locker as he appraoched his 40th birthday to deliver some silverware for them. However in six games he failed to find the net for Shelbourne, and unlike Albert Straka he failed from the spot when presented with his best chance in a Cup match against Shamrock Rovers.

Despite his limitations in the English language Albert Straka was to be more than just a player for Sligo, he was also going to fulfil a coaching role, alongside his joint-coach and fellow player Jimmy Batton, a Scottish defender then lining out for the club. Straka made his debut on the 6th February, 1955 in a League game against a Waterford side who were chasing the League title. The presence of the new signing in the starting XI had the desired effect, at the turnstiles at least. Over 3,000 fans, a record attendance for the season to that point paid £230 in gate reciepts to see the Austrian make his debut. The Donegal Democrat reported that over 250 cars from Donegal and Derry made the journey south for the game, while other papers had reports of long journeys by bicycle or even on foot after early starts from all over County Sligo.

Waterford even though they were missing their star striker Jimmy Gauld through injury, proved too strong for Straka and Sligo, winning a poor game 2-1. The reviews of Straka were not very complimentary, while it seems from the reports that Straka was a danger from set pieces and that he could create good chances with his accurate crossing it was felt that he overall had a limited impact. In fairness most reports listed the various mitigating factors, that he had endured three days of travel to get to Sligo, that he had only just met his teammates who did not speak the same language as him, and that the League of Ireland played a more “robust” style of football than he might otherwise have been used to.

Straka himself, through an interpreter, told Seamus Devlin of the Irish Press that he wasn’t fully match-fit as the Austrian league had finished and he hadn’t played in five weeks, while he also complained of the heavy pitch at the Showgrounds. In the first half he seems to have picked up a minor injury and spent much of the second half relegated to the right-wing as a virtual passenger in the game.

The following match was to be more successful as Sligo surprised many pundits by defeating Shelbourne 3-1 in Tolka Park with Straka linking up especially well with his partner in attack Johnny Armstrong. Straka scored his first for the club, a penalty kick which he “clipped into the corner of the net like he did it every week” in what was to become something of a trademark for the Austrian. There were several mentions of displays of prodigious technique and creativity by Straka who clearly impressed those in attendance. Shelbourne, on something of a bad run of form were without Martin Colfer for most of the game and were effectively down to ten men after losing their star player to injury after half an hour. They also conspired to miss a first half penalty and it really seemed to be a day for them to forget at Tolka and things could have been even worse. Sligo were awarded a second penalty and with the game effectively won rather than let Straka take a second spot kick the opportunity was given to Armstrong who preferred power to accuracy and missed with his kick. The win lifted Sligo off the bottom and gave them a bit of belief that they could avoid having to apply for re-election to the league.

The following week Sligo were back in the Showgrounds hosting St. Patrick’s Athletic who would ultimately go on to be crowned League of Ireland champions that season. Clearly with their confidence bouyed by their result against Shelbourne there was an impressive performance by Sligo, especially in defence, with goalkeeper Tommy Oates and Jimmy Batton earning high praise. The game was tightly contested and Straka had his name taken by referee Michael Byrne after his reacted to a rough tackle by Tommy Dunne. Straka would have some measure of revenge later in the game. Johnny Armstrong made one of his bursting runs and was only denied a goal when one of the Pats defenders cleared ball from the goal-line with his hand. From the resulting penalty Straka “simply stroked the ball into the corner of the net” in what the Sligo Champion described as “one of the best penalty kicks ever taken in the Showgrounds”.

Despite the penalty award the Sligo fans clearly felt aggreived at the refereeing performance of Michael Byrne who was pelted with snowballs on the cold February evening as the match ended and he quickly made his way to the pavillion after St. Pats had snatched a late victory with Sligo down to ten men due to injury. Not content with snowballs some of the other Sligo fans “besieged” the St. Pat’s team bus as they tried to make their exit in the direction of Dublin. There would be more visitors from Dublin soon, the Cup game against Shamrock Rovers was on the horizon, three trains full of fans from Dublin were expected to add to a huge expected local attendance in the Showgrounds.

In the meantime there was the small matter of a trip to face Cork Athletic in the Mardyke. Straka was on the touchline in purely a coaching role, an injury from the ill-tempered St. Pat’s game (perhaps from the attentions of Tommy Dunne) ruling him out as Sligo slumped to a 4-1 defeat. In terms of his coaching the Sligo players were complimentary of Straka’s ideas, all of which had to be communicated via interpreters. Tommy Oates praised his techical ability as a passer and dead ball specialist and most of the players seemed to hve been shocked by the intensity of the phyiscal and fitness training introduced by Straka. However, the heavy defeat to Cork brought home the reality of their limitations.

Which brings us back to the “Straka penalty” and the chaotic game against Shamrock Rovers on March 6th, just over a month after Albert Straka had been first signed. Little did anyone know it at the time but that last minute penalty was to be his last goal for the club. In the replay in Milltown days later the newspaper reports were unforgiving of Straka’s performance as Sligo lost 2-1 with William P. Murphy in the Irish Independent referring to him as the “insignificant Straka” and singling him out as the weakest of the Sligo players on the day and bemoaning the absence of Victor Meldrum from the starting eleven.

Murphy got his wish the following week when Straka was dropped (who did the dropping of the player-coach?) and was replaced by Victor Meldrum (I don’t believe it!) for the visit of Transport. Meldrum didn’t disappoint, scoring twice in an easy 3-0 victory in the Showgrounds. Albert Straka wouldn’t feature again for Sligo Rovers. The next mention of Straka appeared in the Sligo Champion at the end of April to say that he was released from his position of player-coach and was in France and expected to sign for an unnamed French side.

Straka then disappears from the records, certainly in Ireland. In subsequent years his penalty taking ability, especially the spot kick against Shamrock Rovers after a pitch invasion became something ingrained in both the folklore of Sligo Rovers and the League of Ireland more broadly. The judgements made about Straka’s short time the League of Ireland from those who saw him play and those who played alongside him tend to focus on the positives, both Tommy Oates and Victor Meldrum praised his technical ability, which is also attested to by several references in match reports, even those that were not overly complimentary did tend to praise Straka’s skill, trickery and dead-ball mastery. There was an appreciation that as a coach, if nothing else, he significantly raised the fitness levels of his team-mates with his training methods. Where there was criticism, and indeed there was a signifiant amount, especially after the Cup replay, it was at least tempered by the acknowledgment that the League of Ireland differed greatly in its style of football than that more commonly found in Continental Europe.

Speaking years later to the Sligo Weekender in 2017, Paddy Gilmartin, who filled numerous roles for Sligo Rovers said of Straka “he came with a pedigree, he was a very good player and scored a few goals. His style was probably ahead of the League for that time.” This seemed to concur with the view of the Sligo committee back in 1955, returning to the summer AGM of 1955 after Straka had left the club, the club secretary summed up the signing as follows,

“He did not meet…with expectations and while he imparted much information to the team and kept them fighting fit he was just beaten by the type of football played in these islands. The signing of Straka was their second experiment with continental players and as it was felt they did not fit in with the type of game played here no useful purpose was to be gained in recruiting players from these countries.”

Sligo Rovers secretary Charlie Courtney

What became of Albert Straka after he left Sligo is unclear, perhaps he did indeed sign for a French club and his technical skills were more appreciated in a different style of football to the League of Ireland. Having consulted with a couple of Austrian football historians they have confirmed that the much later claims in Irish media that Straka was an Austrian international have no basis in fact. Similarly, the name Straka is not readily associated with any of the Austrian clubs from the 1940s and 50s mentioned in the early reports after his signing by Sligo. My own best guess is that Albert Straka was a decent amateur league player who like other players before and after “exaggerated” on their CV to embellish their footballing credibility and gain a contract. This is as last partly clear from the initial claims that a non-league club like Pottendorf were in fourth place in the Austrian league.

If anyone in Austria, Ireland, France or further afield has any more information on the enigmatic Albert Straka I’d love to hear from you.