An introduction to just some of the Bohemian F.C. members who swapped the playing fields of Ireland for the killing fields of Europe.

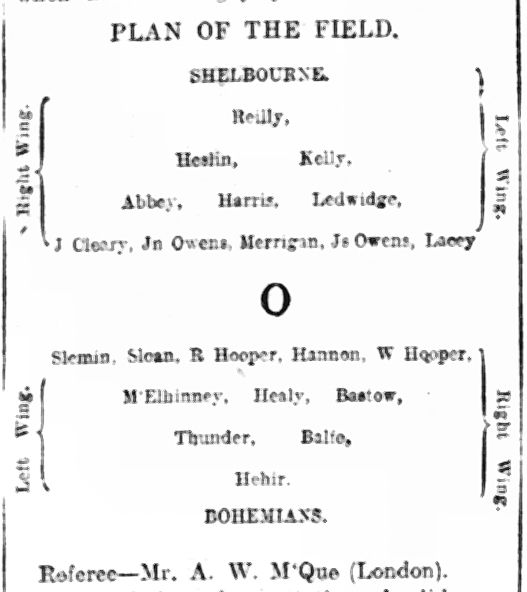

Fred Morrow was only 17 when he took to the pitch for Bohemians at the curtain raiser at their great rivals’ new home, Shelbourne Park. The Bohs v Shels games were known then as the Dublin derby and as with many derbies, passions were inflamed. But this game’s atmosphere was even more heightened and it wasn’t just to do with the 6,000 spectators packed into the ground. Even in just getting to the ground Morrow and his teammates had seen over one hundred Dublin Tramway workers picketing the game.

The 1913 Dublin lock-out was only a few days old and Jim Larkin had declared that there were players selected for the game who were “scabs”: Jack Millar of Bohemians and Jack Lowry of Shelbourne were the names identified during the strike. The striking tramway workers subjected the players and supporters to (in the words of the Irish Times) “coarse insults” and had even tried to storm the gates of the new stadium. Foreshadowing the events of the next day, there were some violent altercations with the officers of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, with 16 arrests made and over 50 people suffering injuries.

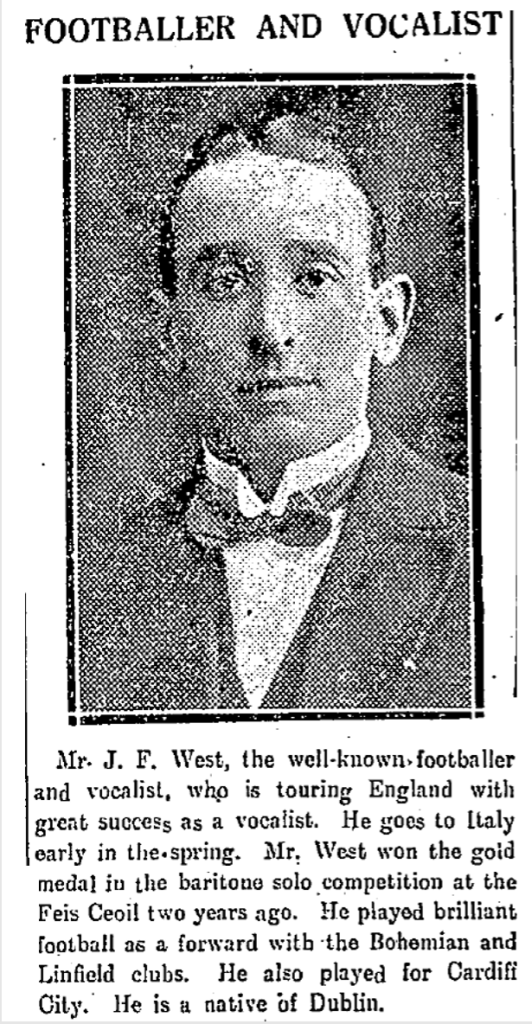

This can’t have affected the teenaged Morrow too badly as he scored Bohs’ goal in a one all draw that day. Although less than 5’5” in height, the youngster was shaping up to be quite a prolific centre forward. Fred had started his career early, lining out for his local side Tritonville FC based in Sandymount, and while with the club he had won a Junior cap for Ireland, scoring in a 3-0 victory over Scotland in front of over 8,000 spectators in Belfast. The following season he’d been persuaded north of the river to Dalymount, and he was to enjoy a successful season including scoring a hat-trick in an unexpected 3-1 victory over title holders Linfield.

The Shelbourne side that Bohs faced that day included in their ranks a new signing of their own, Oscar Linkson, who had just been signed from Manchester United. Linkson had made almost 60 appearances for United and had been at the club when they won the FA Cup in 1909 and the League in 1911. Quite the coup, then, for Shels. Oscar moved to Dublin with his 17 year old wife Olive and his son Eric, who would be joined by a baby sister just months later. He faced Fred Morrow that day as part of the Shels defence.

Within a year of this game, War would be declared. Both Fred Morrow and Oscar Linkson volunteered to serve in the British Army, Oscar with the famous “Football Battalion” of the Middlesex Regiment alongside a whole host of star players which included the Irish international John Doran. Neither Fred nor Oscar would return, by the end of 1917 both were dead on the fields of France.

The events that the players had witnessed leading up to that Bohs v Shels game had far-reaching consequences, with the violence in the adjoining Ringsend streets at the game growing worse over the following day, culminating with violent clashes between the Dublin Metropolitan Police and striking workers on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street). Hundreds were wounded amid baton charges and three striking workers were killed. The dramatic events convinced Union leaders James Connolly, James Larkin and Jack White that the workers needed to be protected, and that an Irish Citizen Army needed to be formed for this purpose. Ireland’s decade of lead had begun.

A year earlier in 1912, in response to the passing of the third Home Rule bill, and the possibility that Home Rule would finally become a reality in Ireland, hundreds of thousands of Irish Unionists signed what was known as the Ulster Covenant, where allegiance was pledged to the King of England. They stated that Home Rule would be resisted by “all means necessary”. This included the very real possibility of armed resistance, as demonstrated by the Ulster Volunteers (formed in 1912) importing thousands of rifles into the port of Larne from Germany in April 1914. In response, the Irish Volunteers, supporters of Home Rule formed in order to guarantee the passage of Home Rule bill, also imported German arms into Howth in July 1914; just days before the outbreak of the First World War. This mini arms-race in Ireland mirrored the greater stockpiling of armour and weaponry by the great European powers in the lead-up to the First World War; the whole Continent was in the grip of militarism. Violence seemed, to many people, to be unavoidable.

Clashes on Sackville Street during the 1913 lock-out

Over 200,000 Irish men fought in the First World War. To put this in perspective, the total male population of Ireland at the 1911 Census was just over 2.1 million. Those who fought did so for many reasons. Some, including many members of the Irish Volunteers, heeded John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party who called on Irishmen to go and fight to help secure Home Rule, as a gesture of fidelity to Britain, in support of Catholic Belgium and in defence of smaller nations.

Redmond asked Irish men to prove “on the field of battle that gallantry and courage which has distinguished our race” in a war that he said was fought “in defence of the highest principles of religion and morality”.

Some men went in search of adventure, unaware then of the horrors that awaited them. Many Dublin men joined up as a way to financially support their families, the city at the time had a population of 304,000, with roughly 63% described as “working class”, the majority of whom lived in tenement houses, almost half with no more than one room per family. The army might offer death but least it offered a steady income.

What we also know is that many Bohemians joined up. Some like Harry Willits or Harold Sloan may have simply joined out of a sense of duty, that this was the “right thing to do”. Most joined in what was known as a “short service attestation”, meaning that they were only joining for the duration of the war, which many mistakenly assumed would be over quickly. In one edition of the Dublin based weekly paper Sport, it was estimated that Bohemians lost forty members to War service, among the highest of any club in the whole country, although we know that there was also significant enlistment from other Dublin clubs such as Shelbourne and Shamrock Rovers, while the loss of players to military service was cited as one of the reasons for the withdrawal from football of the original Drumcondra F.C.

Bohemian F.C. Roll of Honour – Evening Herald, September 1915 source @Cork1914to1924

Some like Harry Willits did return to resume their football career. Several did not return at all. Corporal Fred Morrow, who we met earlier as Bohs centre-forward, was a member of the Royal Field Artillery in France when he died of his wounds in October 1917. His mother had to write formally asking for the death certificate that the armed forces had neglected to send so that she could receive the insurance money for his funeral.

Private Frank Larkin was only 22 when he died just before Christmas 1915. He had been a Bohs player before the war. At this time, due the growing popularity of both the club and football generally in Dublin, Bohs often fielded several teams. Frank featured for the C and D teams, but like many Bohemians, was a fine all-rounder. He played cricket for Sandymount and rowed for the Commercial Rowing Club. He and two of his colleagues from the South Irish Horse were killed by a shell on December 22nd in Armentieres, Belgium. His will left a grand total of £5 14 shillings and 2p to his two married sisters.

Thomas Johnson as pictured at Royal Lytham & St. Anne’s Golf Club in his later years

Thomas Johnson, a young Doctor from Palmerstown was just 23 when the War broke out. He had won an amateur international cap for Ireland and was a star of the Bohs forward line, usually playing at outside right. He was a hugely popular player who the Evening Herald described as “always likely to do something sensational”. He was another fine sporting all-rounder with a talent for both cricket and golf. Johnson became a Lieutenant in the 5th Connaught Rangers during the War and later brought his professional talents to the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Gallipoli. He received numerous citations for bravery, for example at the Battle of Lone Pine during the Gallipoli campaign the Battalion history notes “Second-Lieutenant T.W.G. Johnson behaved with great gallantry in holding an advanced trench during one of the counter-attacks. Twice he bound up men’s wounds under heavy fire, thereby saving their lives”.

While his medical skills were a great asset in saving lives Johnson also was a fierce soldier during the most brutal and heavy fighting. He was awarded the Military Cross specifically for his actions around the attack on the infamous Battle of Hill 60 where so many Irishmen perished. The battalion history states that on August 21st 1915

“Lieutenant T.W.G. Johnson went out to the charge, with rifle and bayonet, and killed six Turks. He shot two more and narrowly missed killing another one. Later, although wounded severely, he reported to the commanding officer, and showed exactly where the remaining men of his company were still holding their own, in a small trench on “Hill 60.”

It was by this means that these men eventually were carefully withdrawn, after keeping the Turks at bay for some hours.” . Hill 60 of course was for many years the name by which Dubliners knew the terrace at the Clonliffe Road end of Croke Park, it was only in the 1930’s that it became known as Hill 16 and later the apocryphal story emerged that the terrace had been built from the ruins of O’Connell Street after the Easter Rising.

Herbert Charles Crozier – back row far left. Harold Sloan – front row third from the right

Other Bohemians suffered serious wounds but managed to make it through to the armistice. One of the most prominent of these was Herbert Charles “Tod” Crozier. He had joined Bohemians as a 17 year old and took part in the victorious Leinster Senior Cup final of 1899. In 1900 he appeared for Bohs on the losing side in an all-amateur Irish Cup Final, which was won 2-1 by Cliftonville. Crozier was described as one of the most “brilliant half-backs playing association football in Ireland” and he formed a formidable and famous midfield trio of Crozier-Fulton-Caldwell who were still revered for their brilliance decades after their retirement. “Tod” had a long association with Bohemians and was also a prominent member of Wanderers Rugby Club. He grew up on Montpellier Hill, close to the North Circular Road and not far from Dalymount.

Major H.C. Crozier

His Scottish-born father was a veterinary surgeon but “Tod” became a career military man with the 1st battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. In 1908 he was awarded the Bronze Star by the Royal Humane Society while serving in Sudan for trying to save the drowning Lieutenant Cooper from the River Nile. It was noted that he behaved with great bravery despite knowing of the “dangerous under-current and that crocodiles were present”. He was a Captain at the beginning of the War and was part of the Mediterranean Expedition Force that travelled to Gallipoli. It was here that he was wounded, and as a result of his actions was awarded the Military Cross, and later, after a promotion to the rank of Major, the Military Star. Despite the wounds he received at Gallipoli he returned to Montpelier Hill in Dublin and continued to attend football and rugby games. He was still enough of a well-known figure that he was the first person quoted in a newspaper report about Bohs progression to the 1935 FAI Cup Final. He lived to the age of 80, passing away in 1961 and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery.

One man who returned from the War and then joined Bohemian F.C. was the legendary Ernie Crawford. Born in Belfast in 1891 Ernie was perhaps best known for his endeavours on the Rugby pitch. He starred for Malone in Belfast and later Lansdowne Rugby Club and won 30 caps for Ireland, fifteen of them as Captain. He would later be named President of the IRFU. His obituary in the Irish Times listed him as one of the greatest rugby full-backs of all time, he was honoured for his contribution to sport by the French government and even featured on a Tongan stamp celebrating rugby icons.

Ernie Crawford in uniform, on a Tongan stamp and as an Irish Rugby international

He was, however, a successful football player who turned out for Cliftonville and for Bohemians. Ernie, a chartered accountant by trade, moved to Dublin to take up the role of accountant at the Rathmines Urban Council in 1919, and this facilitated his joining Bohemians. Despite his greater reputation as a rugby player, Ernie, as a footballer for Bohs, was still considered talented enough to be part of the initial national squad selected by the FAIFS (now the FAI) for the 1924 Olympics. In all, six Bohemians were selected (Bertie Kerr, Jack McCarthy, Christy Robinson, John Thomas & Johnny Murray were the others and were trained by Bohs’ Charlie Harris), but when the squad had to be cut to only 16 players Ernie was dropped, though he chose to accompany the squad to France as a reserve. The fact that he was born in Belfast may have led to him being cut due to the tension that existed with the FAIFS and the IFA over player selection.

That he could captain the Irish Rugby Team and be selected for the Olympics is even more impressive when you consider that during the Great War Ernie was shot in the wrist causing him to be invalided from the Army and to lose the power in three of his fingers. He had enlisted in the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons in October 1914 and was commissioned and later posted to the London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), becoming a Lieutenant in August 1917. He was a recipient of the British War and Victory Medals. Ernie later returned to Belfast where he became City Treasurer. It was in Belfast in 1943 that Ernie encountered Bohs again, as he was chosen to present the Gypsies with the Condor Cup after their victory over Linfield in the annual challenge match. He passed away in January 1959.

So who were these men who went to war? From looking through the various records available (very much an ongoing task) it is clear to see that they were of a variety of different backgrounds. Most were from Dublin, though some like Sidney Kingston Gore (born in Wales) were only in Dublin due to Military placement. Some like Harry Willitts came to Dublin as a young man, others like Crozier and Morrow were children to parents from Scotland, Belfast or elsewhere. They were of various religious beliefs with Catholics, Church of Ireland and Presbyterians among their number.

By the outbreak of the War Bohemian F.C. was not yet 25 years old, some of those who had helped to found the club as young men were still very much involved. The employment backgrounds of the men who enlisted seem to have connections back to those early days when young medical students, those attending a civil service college as well as some young men from the Royal Hibernian military school in the Phoenix Park helped found the club. There were a number who are listed as volunteering for the “Pals” battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, in this case more than likely the 7th battalion. This battalion was made up of white collar workers and many civil servants, they were sometimes referred to as the “Toffs among the toughs”.

The 7th Battalion also featured a large number of Trinity College graduates, as well as many Rugby players encouraged to join by President of the Irish Rugby Football Union, F.H. Browning, a number of those who joined would end up dead on the beaches of Gallipoli. Browning later died after encountering the Volunteers on return from maneuvers at Mount Street Bridge during Easter 1916. The medical profession is clearly represented by men such as Thomas Johnson and J.F. Whelan. There were also characters like Alfred Smith and Tod Crozier who were career military men.

We know that like many Bohemians they were great sporting all-rounders, many being talented Rugby players, rowers, tennis players and cricketers in addition to their talents on the football field. In most cases they were young; Fred Morrow was still a teenager when he joined up, Frank Larkin only 21. Even the prematurely bald Harry Willitts looked much older than his 25 years.

Those who did return from the trenches came back to an Ireland that was changed utterly. The events of the Easter Rising, the growth in Republican Nationalist sentiment and the gathering forces that would soon unleash the War of Independence meant that those who returned may well have felt out of step with the Dublin of 1918-19. Those mentioned above are only a small selection of the Bohemians who took part in the First World War, there are many more stories; of Ned Brooks the prolific centre forward posted to Belfast who ended up guesting for Linfield, of Jocelyn Rowe the half-back who had also played for Manchester United who was injured in combat. There are many others forgotten to history. Those men described above often only appear in the records because of their death or serious injury, many more passed without comment. For men like Harry Willits and Tod Crozier, they could return to familiar surroundings of Dalymount Park whether as a player or just as a spectator. Some of those who returned, like Ernie Crawford, were yet to begin their Bohemian adventure. Among this latter group was a dapper Major of the Dublin Fusiliers named Emmet Dalton. He was a man who had won a Military Cross for his bravery in France and trained British soldiers to be snipers in Palestine. On his return to Ireland, he would join Bohemians as a player along with his younger brother Charlie. Both men would also join the IRA. They would play a central role in the War of Independence and the Civil War though they weren’t the only Bohemian brothers with this distinction as I’ll outline in my next piece.

A partial list of Bohemian F.C.members who served in World War I

Captain H.C. Crozier (wounded, recipient of the Military Cross) 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Later promoted to Major.

Lt-Colonel Joseph Francis Whelan Royal Army Medical Corps, recipient of the Distinguished Service Order for his actions in Mesopotamia (Bohemian player, committee member and club vice-president). Later awarded and O.B.E. as well as an Honorary Master of Science degree by the National University.

Surgeon Major George F. Sheehan, Royal Army Medical Corps. Awarded the D.S.O.

Lieutenant Sidney Kingston Gore, 1st Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment (killed in action). He died after being shot in the head on 28th October 1914 near Neuve Chapelle he was a talented centre-forward who was particularly strong with the ball at his feet.

Sgt-Major Jocelyn Rowe, 1st Battalion, East Surreys (wounded in action). Rowe was born in Nottingham and had briefly played for Manchester United. A report in the Irish Independent of 30th March 1916 stated that Rowe had been wounded an astounding 83 times but was still hopeful of playing football again.

Company Sgt-Major Alfred J Smith, Army Service Corps, (amatuer Irish international, wounded in action)

Private Joseph Irons, on guard duty at the Viceregal Lodge during Easter 1916 he later served duty in the Dardanelles campaign. Irons was born in England and was considered one of the best full-backs in Irish football, he worked on the staff of the Viceregal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin) before being called up to the army from the reserve on the outbreak of War.

Lieutenant P.A. Conmee, Royal Navy (a former Rugby player and a goalkeeper for Bohemians)

Sgt-Major B.W. Wilson Inniskilling Dragoons

Lieutenant JRM Wilson, Bedfords (brother of above)

Reverend John Curtis, Royal Army Chaplains’ Department

Lieutenant Thomas William Gerald Johnson, 5th Connaught Rangers and later Royal Army Medical Corps (wounded in action, awarded the Military Cross for his actions in taking the infamous “Hill 60” during the battle for Gallipoli). Also an Irish amateur international player.

Private Frank Kelly, Army Service Corps

Lieutenant Ernie Crawford, Inniskilling Dragoons and Royal Fusiliers

Corporal F. Barry, Black Watch

Second lieutenant Charlie Webb, King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He was captured in March 1918 near Nesle in Northern France and saw out the war from a Prisoner of War camp near Mainz. Webb was an Irish international forward who was born into a military family in the Curragh Camp, Co. Kildare. He played for Bohemians between 1908-09 but is most associated with Brighton & Hove Albion where as a player he scored the winning goal in the 1910 Charity Shield Final. He later became Brighton’s longest serving manager, beginning in 1919 and continuing until 1947, a span that covered over 1,200 matches.

Private James Nesbitt, Black Watch (killed in action 16/07/15) the son of W. H. and Jeannie Nesbitt, of 54, North Strand Road, Dublin. James was a Customs and Excise Officer at Bantry, Co. Cork, at the outbreak of war. Although badly injured he directed medical attention to other wounded men. He walked back to the field hospital but died soon afterwards. Nesbitt was also a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party who sat on Blackrock Urban Council. He was known as the “Battalion Bard” as he amused the other troops by writing and singing “topical songs”. Nesbitt mostly played for the Bohs C and D teams.

Private A. McEwan, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Private P. O’Connor, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Private A.P. Hunter, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Private J. Donovan, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Sergeant Harry Willitts, Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Sergeant Harrison McCloy, Tank Corps. (Killed in action) McCloy was born 12th December 1883 in Belfast. He continued a common tradition of being a footballer for Clinftonville before joining Bohemians. He was a player for Bohemians from 1902 to 1905 including appearing for the first team in the Irish League. He later moved into an administrative role and was a club Vice President for Bohemians from the 1905-06 season through to 1911-12, He was also mentioned as having been Honorary Secretary of the Irish League in 1911. He had been part of the Young Citizens Volunteers before transferring to the Tank Corps serving as a Quartermaster Sergeant during World War I. His main role was supervision and security of tanks used in battle pre or post engagement. He was killed in Belgium by enemy shellfire on the 21st August 1917 whilst engaged in such duties. He was 33 years old. Buried in the White House Cemetery St-Jean-Les-Ypres. His gratuity was left to four of his siblings.

Corporal Fred Morrow, Royal Field Artillery (formerly of Tritonville F.C. Bohemian F.C. and Shelbourne), killed in action 1917.

Private Angus Auchincloss from Clontarf joined the Army Cycling Corps in 1915 and transferred to the Royal Irish Rifles in 1916. He was discharged in 1919 and died in Eastbourne, England in 1975 at the age of 81.

Lieutenant Harold Sloan, Royal Garrison Artillery killed in action January 1917.

Major Emmet Dalton, Royal Dublin Fusiliers. On returning to Dublin Dalton became IRA Head of Intelligence during the War of Independence and later a Major-General in the Free State Army.

Lieutenant Robert Tighe, 5th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers

Private G.R. McConnell, Black Watch (wounded)

Trooper Francis Larkin, South Irish Horse (killed in action)

Major Fred Chestnutt-Chesney, 6th Lancashire Fusiliers (former goalkeeper for Bohemians and for Trinity College’s football team). Later a Church of Ireland Reverend. Wounded in combat by a gun shot to his left leg.

Private J.S. Millar, Black Watch

John C. Hehir, the star goalkeeper for Bohemians until January 1915. He was also capped by Ireland in 1910. Hehir played rugby for London-Irish and also won a Dublin Senior Club championship medal with the Keatings GAA club in 1903. He left Bohs to take up an “important role” with the War Office in London

Lieutenant William James Dawson, Royal Flying Corps. Injured in 1917 he returned to action but died in 1918. He was also a member of the Neptune Rowing Club and the Boys Brigade.

Captain J.S Doyle, Royal Army Medical Corps

William Henry (Billy) Otto, South African Infantry

Private F.P. Gosling, Black Watch and later the Machine Gun Corps

Lieutenant L.A. Herbert, Veterinary Corps

Private Bobby Parker, Royal Scots Fusiliers. Parker was the English First Divisions top goalscorer in the 1914-15 season as he helped Everton to the League title. However, after league football was suspended Parker enlisted and was wounded in early 1918. Despite attempts to continue his playing career the bullet lodged in his back essentially meant his time as a player was over at the age of 32 after a brief spell with Nottingham Forest. Parker moved into coaching and in 1927 was appointed coach of Bohemian FC, a position he held until 1933. He led Bohemians to a clean sweep of every major trophy in the 1927-28 season.

Private William Woodman, 7th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers and his brother Private Albert Woodman, Royal Engineers. After the war Albert returned to his job at the General Post Office, working there until his retirement. During World War II, he worked as a censor and redactor. He bought a home on Rathlin Road, in Glasnevin. Albert passed away in 1969, at the age of 78. For more on the Woodman family see here.

Private Stephen Wright served with the Leicestershire Regiment and the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I. Born in Leicester he had two spells with Bohemians, before the outreak of the war, and again in the 1919-20 season. He would also appear for Bolton Wanderers, Norwich City and Brighton and Hove Albion. He returned to Ireland as a coach after breaking his leg while at Brighton, taking up a role at Dundalk in 1930 and leading the Louth club to their first ever league title in the 1932-33 season.

Private F. W. Taylor

Corporal H. Thompson, Royal Engineers

Trooper Griffith Mathews, North Irish Horse

Part of a series of posts on the history of Bohemian F.C from 1913-1923. Read about Bohs during Easter 1916 here or about the life and career of Harry Willits here.

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory