Get your Crosses in

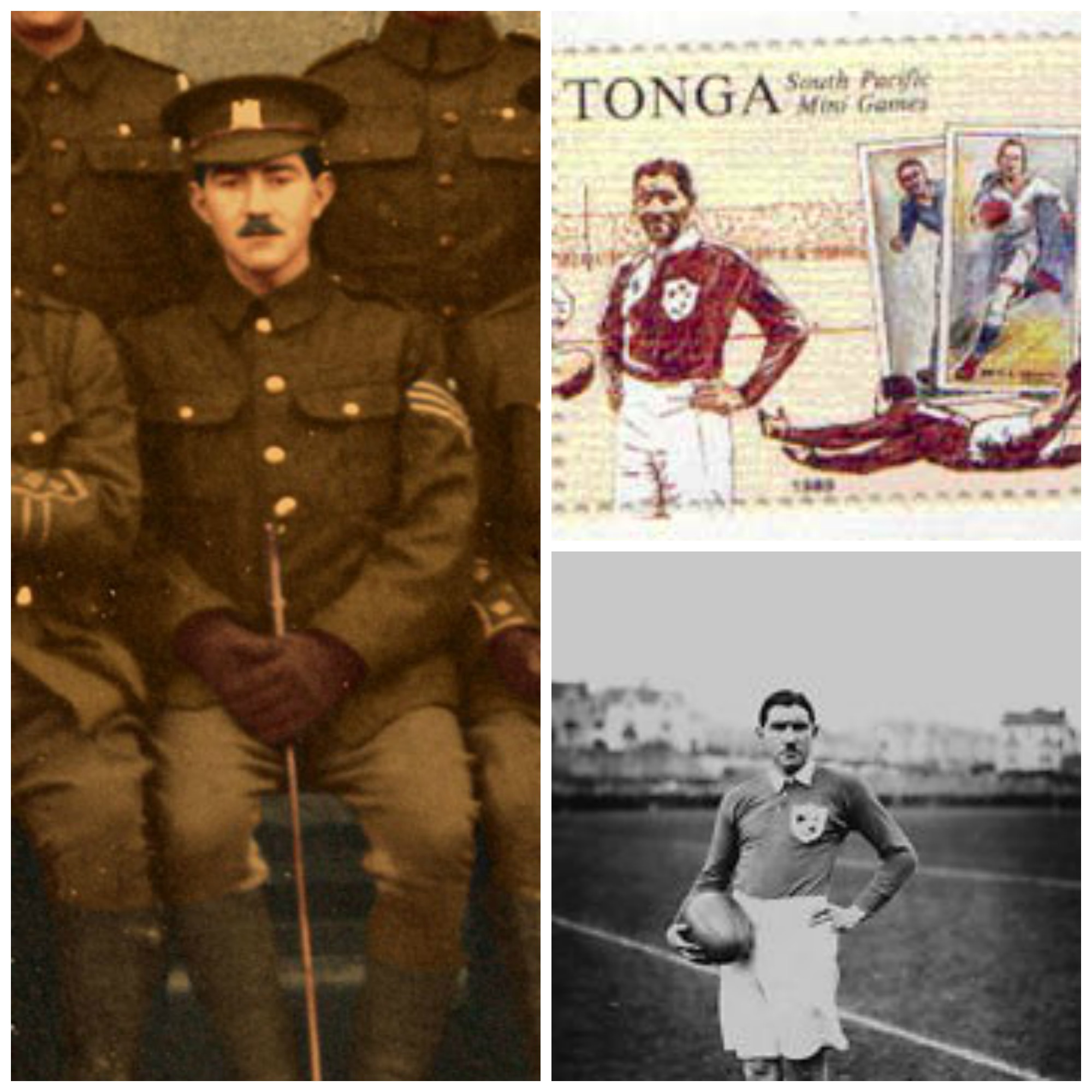

On a cold day in October 1980 a teenaged Grainne Cross, a versatile midfielder, was sent on as a substitute to try and break the deadlock in an international friendly against Belgium at Dalymount Park. With 15 minutes gone in the second half and the score still tied at 0-0 a ball was lofted into the box, Cross got onto the end of it and scored with a beautiful header but was crashing into by the onrushing Belgian goalkeeper. Both players were taken by ambulance to be treated for their injuries and it was only later that Grainne learned she had in fact scored the winning goal of the game. For, Grainne it was one of her, surprisingly, favourite memories from a sporting career that included a move to Italy, playing in Wembley and starting at scrum half for Ireland in a Rugby World Cup!

Grainne was born into a large, sports mad, Limerick family, her father had been a good rugby player and hurler, and her brothers all played rugby as well. However, Grainne and her sisters really excelled at football, Grainne, Tracy and Rose would all be capped by Ireland during their sporting careers.

Grainne began playing in her teens and her talent was quickly spotted, women’s football in the area was mostly focused around factory teams and Grainne appeared for De Beers in Shannon where her mother and sister worked, as well as lining out for other factory teams like Krupp’s and regularly guesting for other sides such as Green Park.

Grainne was talented, (she won her first cap as a 15 year old) and she grabbed the attention of American Colleges who were interested in offering sports scholarships but Grainne followed a different path. Inspired by the success of Anne O’Brien in Italy she contacted the Italian Federation stating her interest in playing in Italy. Amazingly, this paid dividends, what Grainne thought was going to be week-long trial with ASD Fiammamonza in the city Monza, near Milan, turned into a contract offer and chance to pit her wits against the likes of Anne O’Brien, Rose Reilly and Carolina Morace, all gracing the Italian game at the time.

Grainne recalls the professionalism she encountered in Italy, simple things like good playing surfaces, bigger stadiums with crowds of up to 10,000, and not having to wash her own kit. She also remembers the step up in quality as she faced the some of the best players in Europe. Ultimately homesickness ended her stay in Italy after a season, she had initially had to live with her coach and his family, and expecting only to be on a trial hadn’t had a chance to learn much Italian before she left for Monza.

Her career continued with Ireland and she got the chance to play in Wembley in 1988, where as part of the Football League Centenary celebrations she played against her English League counterparts and remembers bumping into the likes of Bryan Robson and Paul McGrath who were playing for Manchester United in the centenary celebrations that day. While Grainne continued to play football her work commitments, including spells working in England and the United States limited her availability for Ireland matches.

In her late 20s as Rugby became more accessible to women Grainne began playing for Old Crescent helping the club to considerable successes, so much so, that she was selected as part of the squad that represented Ireland at the 1998 Rugby World Cup, starting as a scrum half against the Netherlands before an injury limited her participation in the tournament. She’s even been known to dabble occasionally in the GAA codes, a real sporting all-rounder.

To this day Grainne remains an enthusiastic supporter of both football and rugby and is hopeful for the future of the Irish national team.

With thanks to Grainne Cross for taking the time for this interview which first featured in the Irish international match programmes.