It could happen to a Bishop – John Curtis in faith and football

A Bohemian history of the 20th Century: An examination as to whether it is possible to write about the key events of the last century through reference only to those people who played for Bohemian Football Club of Dublin. A difficult task but the more I read and research, perhaps not an impossible one. Thus far there are Bohemian connections to the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War in Irish history, and in a wider context there were the global conflicts of World War I and II which I have mentioned in previous posts. But how about Chinese missionaries and the rise of the Maoist interpretation of Communism? Well to tell that story we have to go back to Dublin in 1880.

John Curtis was born in 1880, as the eldest son of Thomas Hewson Curtis and Margaret Curtis. Thomas was a clerk and later a manager in the corn exchange near to Christchurch Cathedral but as a youngster John lived with his family on Montpellier Hill its steep incline rising to the North Circular Road gate of the Phoenix Park where Bohemian F.C. would be founded in 1890 by a group of men only a few years senior to young John. By that time the growing Curtis family had moved the short distance to Blackhall Street, residing in a house next to the Law Society buildings at Blackhall Place which were then occupied by the King’s Hospital school. Eventually the family moved to Hollybrook Road in Clontarf as Thomas’ career continued to progress. The young John was educated not in King’s Hospital but at Benson’s Grammar School in Rathmines which was founded by Rev. Charles William Benson on the lower Rathmines Road, the school also educated the likes of George Russell (AE) and members of the Bewley family. John then graduated to study in Trinity College Dublin.

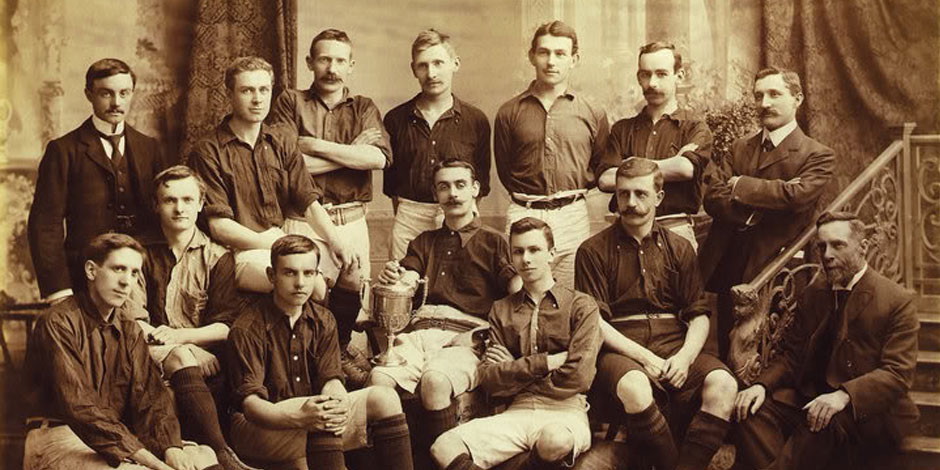

It was around this time that a teenage John Curtis first made an appearance for Bohemians. He appears in the first team in the 1897-98 season. He played most of his games for the club at inside-left, and in that first season his partner at outside-left was none other than Oliver St. John Gogarty. The pair starred together as Bohemians won the 1897-98 Leinster Senior Cup final, defeating Shelbourne 3-1 while also progressing to the semi-finals of the Irish Cup.

The following season showed a similar pattern, another Leinster Senior Cup win and another lost Irish Cup semi-final (this time to Linfield) for the Bohs and John Curtis. Though not yet 20 Curtis was already a star player, in the 18 games he played that season he scored an astonishing 21 goals. Bohemians wouldn’t join the Irish league until the 1902-03 season so Cup competitions such as the Leinster Senior Cup and the Irish Cup, as well as the Leinster Senior League, would have taken precedent at the time and Bohemians were clearly the strongest side outside of Ulster at that juncture.

The 1899-1900 season saw further progress in the Irish Cup, this time Bohs got all the way to the final. John Curtis was instrumental in getting them there, scoring a vital equalising goal in the semi-final against Belfast Celtic before Herbert Pratt scored the winner in a match played in the Jones Road sports ground, now better known as Croke Park. John lined out against Cliftonville in the final in Grosvenor Park in Belfast in front of 5,500 spectators. Alas it didn’t turn out to be a first cup win for Bohemians.

Bohs had made it to the cup final once before in 1895 when they were hammered 10-1 by Linfield, but the 1900 final was to be a much closer affair with Bohs being defeated 2-1 with George Sheehan getting the goal for the Dublin side. The newspaper reports described a tight game with Bohs deemed to have been highly unlucky to lose, indeed many observers thought that Cliftonville’s second goal was a clear offside. Matters weren’t helped by four Bohemian players picking up knocks during the course of the match.

On a personal note for John Curtis it seemed that just a week prior to the Irish Cup final he might be honoured with an international cap. A first ever international game was to be staged in Dublin’s Lansdowne Road and Andrew Gara, the Roscommon born, Preston North End forward was earmarked for a spot in the Irish attack, however just days before the game Gara was injured and the Irish Independent reported that his place was to be awarded to John Curtis. This didn’t come to pass however, the sole Dubliner in the line-up was John’s team-mate George Sheehan who was given the honour of captaining Ireland in a 2-0 defeat to England. The closest John would come to an international cap would be representing Leinster in an inter-provincial game that season against an Ulster selection.

While John Curtis would continue to line out for Bohemians his appearances were reduced in number over the coming years, he had sporting commitments with Trinity College as well, representing them in as a footballer in the Irish Cup while also enjoying games of Rugby.

John Curtis is the big bloke with the moustache and his arms folded in the back row.

He features in a team photo from the 1902 Leinster Senior Cup winning photo but lined out for the club less frequently, he did appear in a couple of prestigious friendly matches in the early years of the century however, when Bohemians were keen to invite the cream of British football to their new home in Dalymount Park. John played against Celtic in 1901 and against Bolton Wanderers the following year.

By 1903 John had finished his studies in Trinity College and was ordained as a Reverend, his first parish being that of Leeson Park in Ballsbridge. By this stage his two younger brothers Edward (Ned) and Harry were both playing for Bohemians, though with less distinction than their older brother.

While his footballing life might have been coming to somewhat of an early close the even more remarkable parts of John Curtis’ story were only beginning. After only three years in his Dublin parish John Curtis was setting sail for missionary work in China and embarking on a whole new chapter in his life.

John was bound for the Chinese province of Fujian on the southwest coast of the country. The first Protestant missionaries had only begun working in China in 1807 and among the early missionaries was another Irishman, William Armstrong Russell who arrived in China in the 1840’s. Despite these earlier arrivals John’s journey was still very much a leap into the unknown and certainly a long way from leafy south- Dublin parish work.

John arrived in Fujian in 1906 and later, while working there met fellow missionary Eda Stanley Bryan-Brown, she had been born the daughter of a clergyman in Australia, and in 1914 they were married. In 1916, – perhaps out of a sense of duty? – John returned to Europe in the midst of War, this meant separation from his wife and his missionary work. Curtis joined the British Army Chaplains and shared the dangers of the combat troops in trenches and on battlefields. He spent time in Greece and also would have ministered to members of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during his service. As one journalist who knew him well observed of his character “one cannot picture him holding back from that cataclysm”. Indeed despite his obvious religious devotion most descriptions of John Curtis focus strongly on his energy and fearlessness, whether on the sports ground, or the battlefield or in his missionary work.

Luckily John survived the War and in 1919 received the Victory medal, however he swiftly returned to his work in China. Since arriving in China in 1906 John had witnessed crowning of the child emperor Puyi in 1908 as well as his forced abdication, the end of Imperial rule, and the founding of the Republic of China just a few years later. His post-war return witnessed further upheaval. In 1927 John and his missionaries would no doubt have been aware of the first major engagements of the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (or KMT, the major political party of the Republic) and the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party. There was a major battle for control of the city Nanchang in the neighbouring province of Jiangxi which ultimately saw the Communist forces flee in defeat, many of their surviving troops marched hundreds of miles to take refuge in Fujian, the province where John and his family were living.

By this stage John and Eda had become parents to a son, John Guy Curtis in 1919, Arthur Bryan Curtis in 1924 and followed by a sister, Joan. It was a restless time to have a new family but there was further change for John as in 1929 he became Bishop of Zhejiang, replacing his fellow Dubliner Herbert Moloney. This meant that John and Eda moved to the beautiful city of Hangzhou, referred to by some at the time as the “Venice of the east” due to its location on the Grand Canal of China and sections of the Yangtze river delta. By this stage Eda had brought the children to England in 1927 to live with one of her brothers though both parents visited every year up until the outbreak of the Second World War. In their young lives the children had witnessed a great deal of violence. Joan recalled as a four year old hearing “soldier and their cannon” from the Missionary school. On another occasion in 1922 Eda and her two young children were obliged to undertake a long journey up river, during the course of which her oldest son John by then only three years old at the time developed laryngeal diphtheria. When it looked like he might succumb to his illness she was forced to perform a tracheotomy, her only instruments being a pen-knife and some hair-pins. It was perhaps not surprising that the calm of rural England would seem a better place for the children to grow up.

Drama and upheaval followed the Curtis family to this new setting of Hangzhou and as Christmas 1937 approached so too did the forces of Imperial Japan. The Second Sino-Japanese war had broken out that summer and on Christmas day 90,000 Japanese troops entered Hangzhou after fierce fighting. A week earlier the Japanese had advised all foreign consuls to evacuate any of their citizens from the area due to the danger of the fighting, in all there were only 31 foreigners in Hangzhou in 1937 and John Curtis was the only Irishman.

Journalist and Church of Ireland priest, Patrick Comerford notes that “living conditions deteriorated in the city, Curtis constantly visited the hospitals, medical camps and refugees, his overcoat pockets bulging with bottles of milk for the children. On what he called his ‘milk rounds,’ he also shepherded large numbers of frightened women and children to the safety of the refugee camps.”

He continued to administer to his Church’s followers throughout his vast diocese despite the restrictions caused by the Japanese invasion, and the subsequent outbreak of World War II. By September 1942 more than nine months after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbour many missionaries were called in for questioning. John Curtis was arrested in November and taken to the Haipong Road Camp in Shanghai and then held in Stanley Internment Camp, Hong Kong. Comerford writes that on one occasion, “the Japanese threatened to shoot him if he continued to criticise their treatment of his fellow prisoners, but it was said that in internment he was a great asset to the morale of the camp.”

The Curtis’s would remain in prison of war camps for the remainder of the War, it was in such a camp that they would learn of the death of their oldest son John, in January 1943. John, whose life Eda had saved as a toddler, was only 23 when he died in a flying accident while on service as an RAF pilot. When finally released from the camp at the end of the war both John and Eda were in their 60’s and had suffered cruelly during their captivity. Eda had continued her medical work, helping other prisoners inside the camp and her thoughts were about returning to Hangzhou to continue her work at the mission hospital, which they managed to do with support from the Red Cross. After the war more missionaries did come out to China from Ireland and Britain however their work was made increasingly difficult under the rule of Chairman Mao Zedong. Eventually in 1950 John and Eda left China for the last time and returned to England.

John became a vicar in the small village of Wilden, north east of Stourport-on-Severn in Worcestershire before he eventually retired to Leamington in 1957 at the age of 77. Although struggling with arthritis it was noted that he remained in good spirits when in conversation with his old friends, and he kept in contact with his many old acquaintances and was eager for news from Dublin, indeed he had continued to visit Dublin regularly even while working in China. John was highly thought of as a missionary and often during his returns to Dublin he was asked to speak about his work and travels. And despite the passing of time his reputation as one of the best Irish footballers of his generation lived on for decades as well.

John passed away suddenly in 1962 and Eda died just 18 months later. They had truly lived full, dramatic and difficult lives. Their daughter Joan got married and ended up living in Sligo while their surviving son Arthur Bryan Curtis, who had studied at Oxford and also served in World War II ended up emigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to become a school headmaster.

The sporting connection begun with John Curtis all those years ago for Bohemians continued with his son. John had been a handy Rugby player in his Trinity days and Arthur Bryan also excelled with the oval ball, playing for Oxford University and London Irish. In 1950 he won three Irish international caps as a flanker. Arthur’s son David also represented Ireland at Rugby, winning 13 caps and appearing as a centre during the 1991 Rugby World Cup, David was also a useful cricket player and represented Oxford University in that sport. Continuing a family tradition David’s sons Angus and Graham are currently playing Rugby with Ulster and Angus has already been capped for Ireland at under-20 level.

But however exceptional the sporting careers of the younger Curtis men might be it cannot match the drama of their ancestor, the famous Bohemian John Curtis, or his wife the fearless Doctor, Eda Stanley Curtis.

Many thanks to Stephen Burke for providing information on John Curtis’s playing career. Also for more on Irish missionaries in China check out Patrick Comerford’s blog.