It all began in a two room house that no longer stands, on a street that no longer exists. In the summer of 1911, Joseph O’Reilly, a man who go on to be one of the greatest Irish footballers of his era was born at number 4, Willet’s Place. And, like the street where he was born, O’Reilly tends to be forgotten by history.

While Willet’s Place was just one of the many lanes and courts that snaked through Dublin’s impoverished north inner city, a place that many perhaps willingly forgot, Joe is someone who should be more familiar, especially to Irish football supporters. He was the first Irish player to win twenty international caps, a total that would have been significantly higher had the outbreak of World War Two not intervened. O’Reilly’s appearance record wouldn’t be broken until Johnny Carey won his 21st cap in 1949.

He was also a star of the domestic game, winning both a League and an FAI Cup with St. James’s Gate and represented the League of Ireland XI on many occasions. However, despite being a cultured half-back with a rocket of a shot, enjoying club success and scoring on his international debut in a win against the Netherlands, O’Reilly’s name provoked little response when typed into a search bar – a two line wikipedia entry being scant reward for an impressive career.

One reason that Joe O’Reilly is not a more prominent name in the history of Irish football could be down to the man himself. I spoke with Joe’s son Bob about his father and he stressed how little his father courted the limelight, describing him as a quiet and very humble man. Indeed the few articles and interviews that one can find on Joe O’Reilly see him focus praise and attention on his erstwhile teammates and rivals rather than on himself.

Ordnance survey map showing Willet’s Place (top centre right) c.1913 the Gloucester Diamond is shown bottom left.

Off the Diamond

To redress the balance I’ve tried to piece together a descriptive timeline of Joe’s life and career. In doing so let’s return to that two bedroom house in Willet’s Place, a back lane off what we know today as Sean McDermott Street. On May 27th 1911 a son is born to Michael and Mary O’Reilly, they christen him Joseph. This is an area that will become synonymous with Dublin football and footballers, Graham Burke, Jack Byrne and Wes Hoolahan are some of the more recent residents from the area who have worn the green, while the Gloucester Diamond became famous across the city for its 7-a-side matches that often featured the cream of Dublin’s footballing talent.

The Gloucester Diamond and its famous 7 a side concrete pitch – photo from local historian Terry Fagan

However, the O’Reilly family would not remain in the area long, they moved to another hotbed of Dublin football; Ringsend on the southern banks of the Liffey. Michael was a soldier in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers at the time of Joe’s birth and he was predominantly based out of Beggar’s Bush barracks, a short distance from the Ringsend/Irishtown area. The cramped house on Willet’s Place was the family home of mother Mary and shared with her parents Joseph and Mary-Anne Cooling. By 1916, when Joe’s younger brother Peter was born the family were living in one of the newly constructed houses in Stella Gardens, Ringsend. Named after Stella O’Neill, the daughter of local Nationalist Councillor Charles O’Neill these would have been an improvment on Willet’s Place and would have been highly sought after.

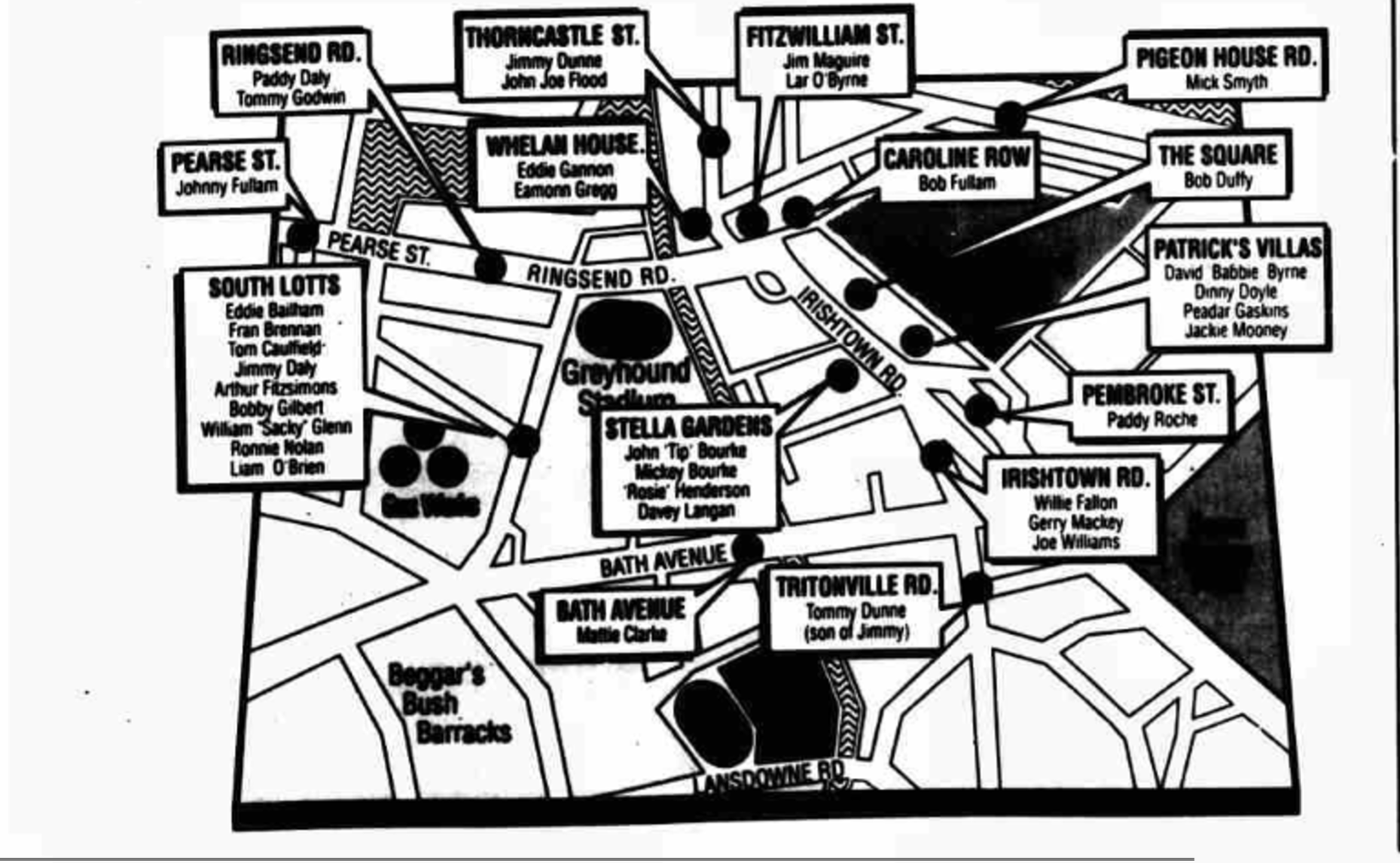

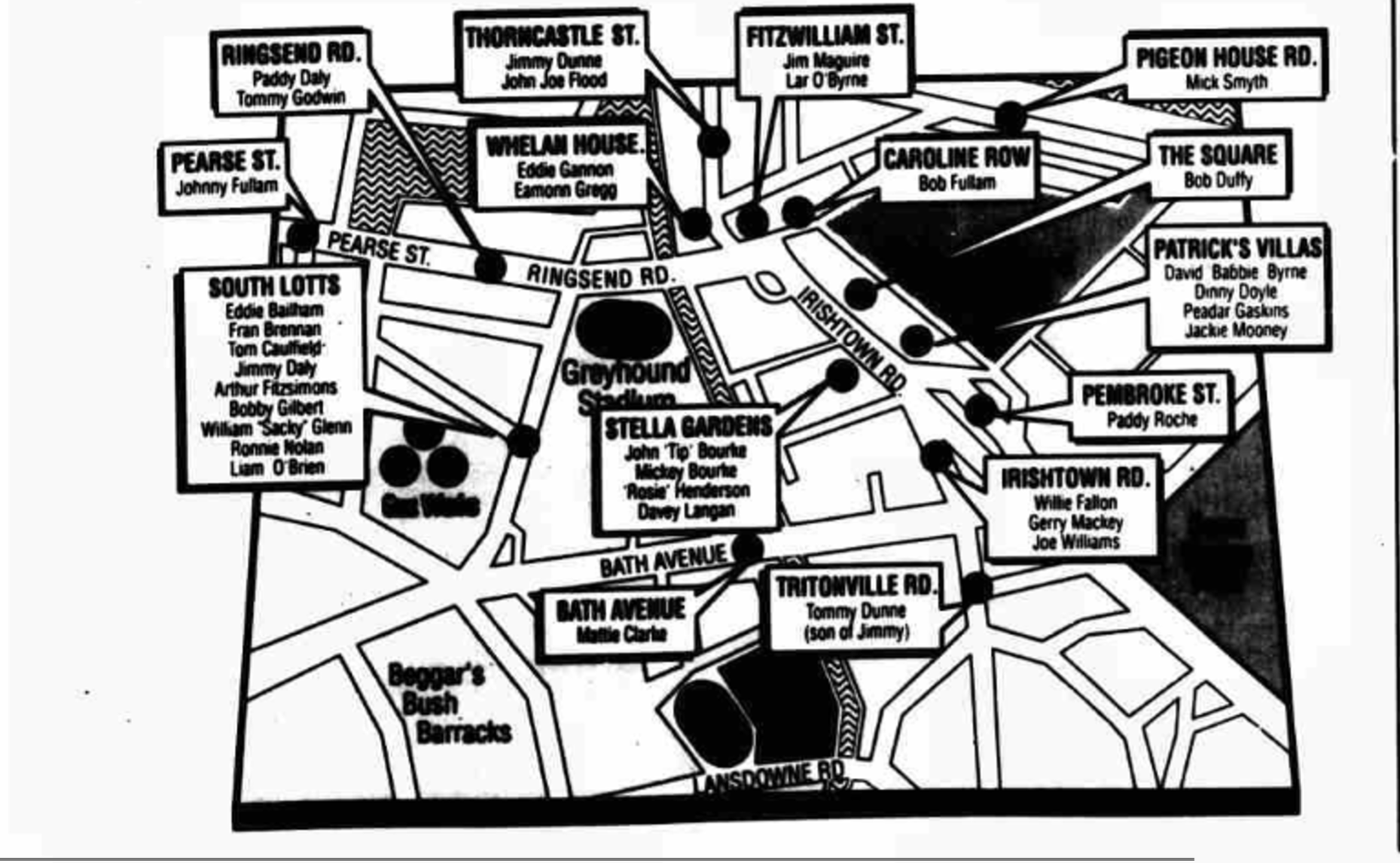

The family remained in the Ringsend area although the moved addresses at various times, being listed as living on the likes of South Lotts Road and on Gerald Street. Joe was the third child in a growing family that eventually would welcome seven children, four boys and three girls. Ringsend is of course an area synonymous with soccer, being the original home to both Shamrock Rovers and Shelbourne as well as one of Dublin’s oldest football clubs, Liffey Wanderers. The district has supplied the Irish national team with literally dozens of international players over the years and should count O’Reilly among its number, although he didn’t make the list when the Sunday Tribune set out to map all of Ringsend’s footballers back in 1994 (see below).

Sunday Tribune 1994 map of Ringsend’s footballers

The Ringsend Cycle

While born on the northside of the Liffey, and later to spend much of his life living in the then rural village of Saggart, south county Dublin it would be Ringsend that would provide formative influences on young Joe O’Reilly. Ringsend was home to Jimmy Dunne, who O’Reilly played with on numerous occasions for the national team, a man that he would continue to tell tales about years after he had hung up his boots. Ringsend was also home to Bob Fullam, one of the bona fide stars of Irish football in the 1920s, when terraces used to echo to the chants of “Give it to Bob”, in the hope that his rocket like left foot would create something spectacular. We’ll come on to Fullam later in our story but let’s begin with Dunne.

Jimmy Dunne was born in 1905, six years senior to Joe O’Reilly and packed a lot into those early years. While still a teenager he was interned by the Free State forces in the “Tintown” camp in the Curragh due to his involvement with the anti-treaty IRA, his older brother Christopher was also involved. By that stage Dunne was already something of a footballing prodigy and fellow footballer, and internee Joe Stynes remembered playing matches with Dunne in the cramped confines of the camp. According to O’Reilly’s son Bob, the Republican exploits of Jimmy Dunne extended back even further. During the War of Independence he remembered his father saying that Jimmy Dunne (then no more than 15 or 16) was a delivery boy for a local baker, and would use this job as a way to bring IRA messages across the city on his bicycle, hidden inside a loaf of bread.

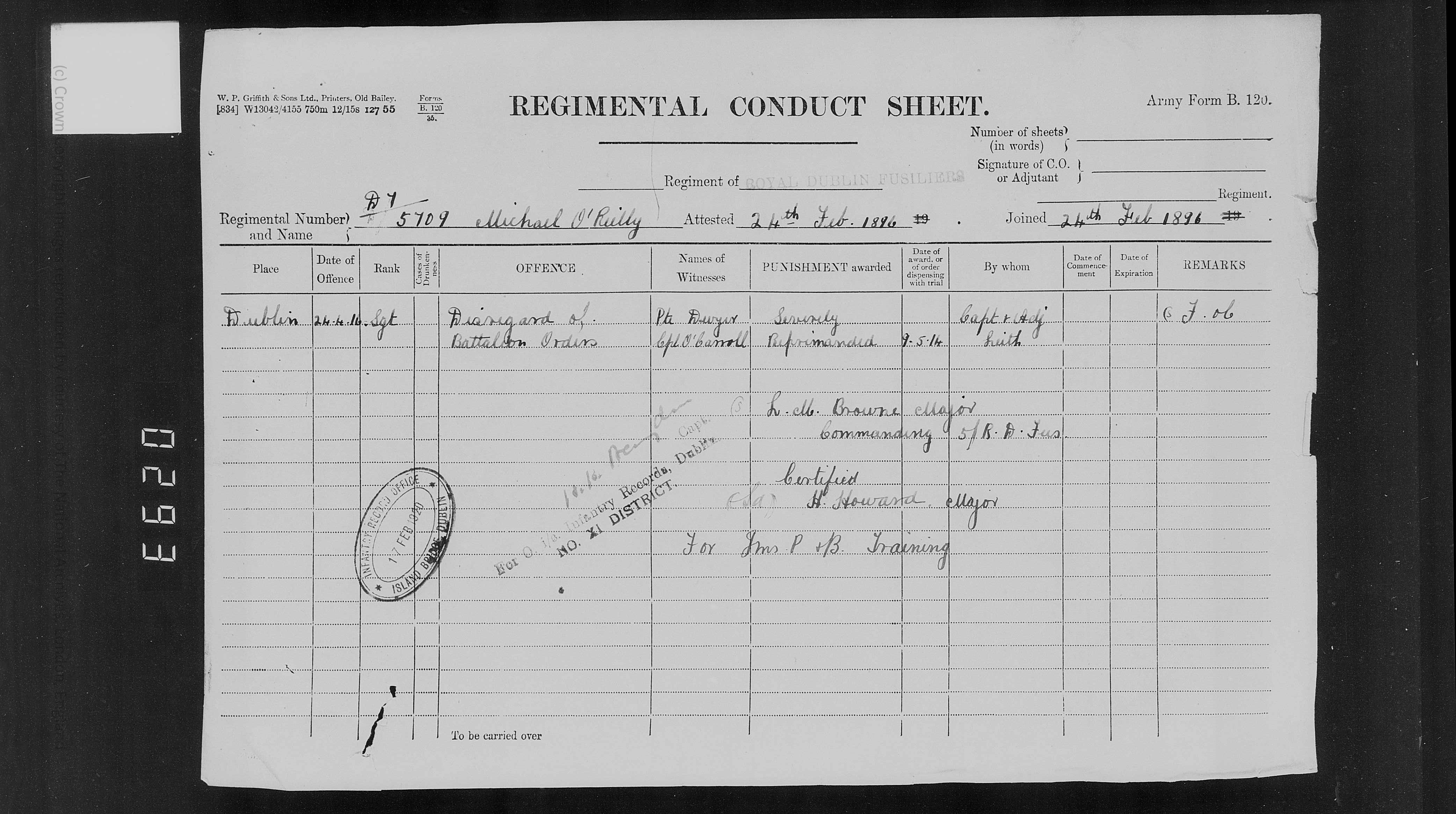

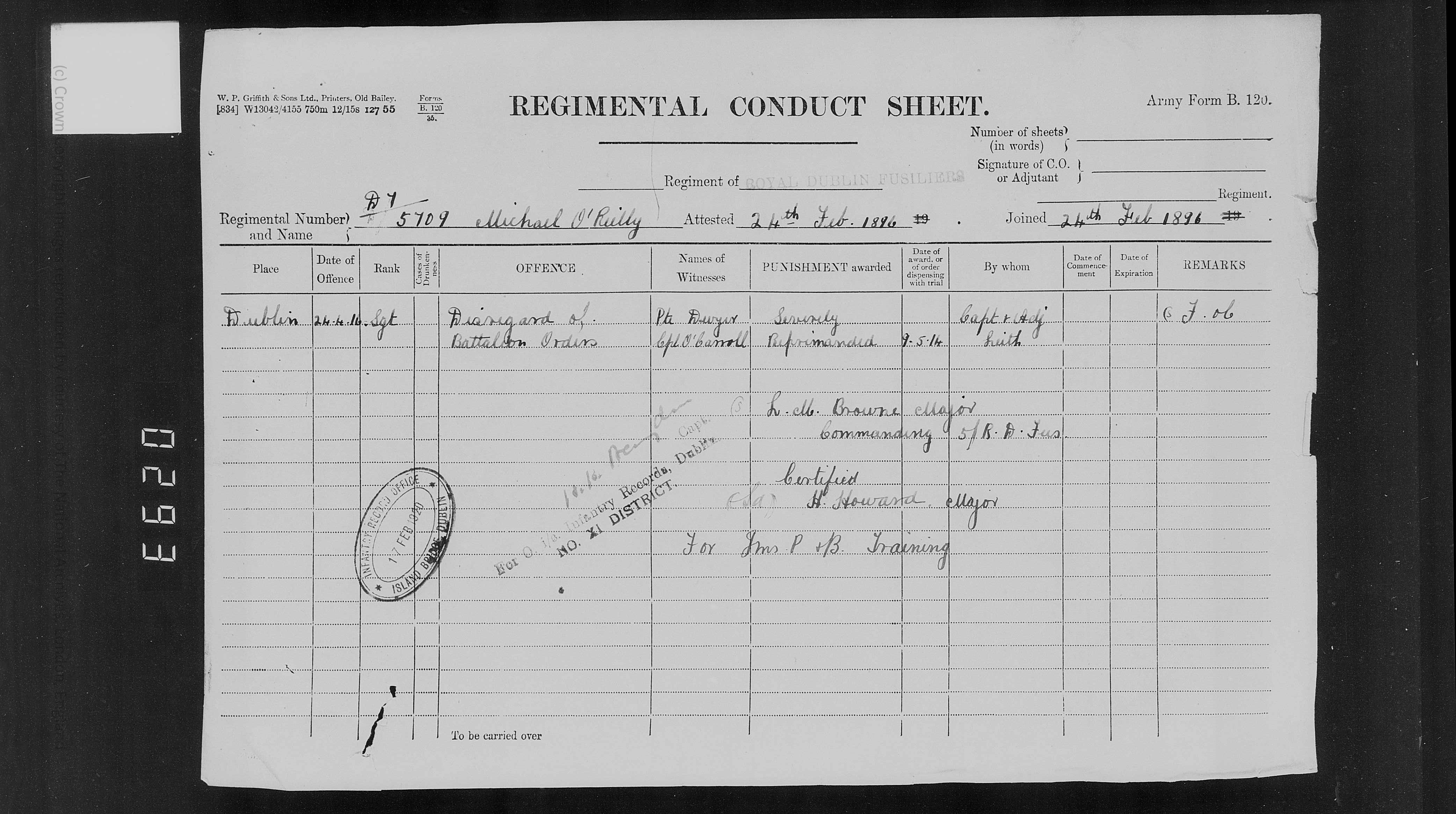

An additional layer is added to this when we turn to the life and career of Joe’s father Michael. As mentioned above Michael O’Reilly was a soldier with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. More than that he was a career soldier, having joined aged 18 and risen to the rank of Sergeant-Major and becoming and physical education instructor for the troops. He was a veteran of the Second Boer War and had an unblemished service record. Well – unblemished apart from one incident which caused him to be “severely reprimanded”. This reprimand related to a “disregard of battalion orders” when his battalion was based in Beggar’s Bush barracks in Dublin on the 24th of April, 1916. The day the Easter Rising began.

Reprimand issued to Michael O’Reilly on the outbreak of the Easter Rising

The specifics of this incident remain unclear but it worth noting that Michael O’Reilly was not a callow recruit, he was a 29 year old Sergeant with over ten years service and battle experience. According to family history Michael gradually became disillusioned with life in the Army and even began training IRA volunteers during the War of Independence after leaving the British Army in early 1920. We do know that he would go on to join the newly created Free State army and would be based in the Curragh camp during the War of Independence, perhaps he even watched his son’s future teammate Jimmy Dunne play a match in the Tintown prisoner camp?

Debuts and defeats

Joe O’Reilly would follow his father into the Army as a young man and was a member of the Army No. 1 band as a clarinet player. While in the army he also lined out for an unofficial Army football team, Bush Rangers (the Association game wasn’t recognised as an official army sport at the time) and it was clear that football was his first love. Aged just 18, Joe O’Reilly made his debut in the League of Ireland, helping Brideville to a win over Dundalk in October 1929. Joe started at the inside right position and scored in the win over Dundalk. Of his debut the newspaper Sport recorded –

“O’Reilly the newcomer, lacks training but he was responsible for many clever touches and a fine goal. He should be persevered with.”

And persevere they did. By the end of that seasons the teenage O’Reilly was a regular for Brideville as they finished fifth in the League of Ireland and was lining out in a Cup final against Shamrock Rovers who were embarking on a famous Cup dynasty. O’Reilly remembered being somewhat overawed by the occasion. He was not yet 19 and here he was starting in front of almost 20,000 in Dalymount Park, facing off against Irish internationals. He recalled years later that he must have looked somewhat of a nervous wreck as Rovers’ star Bob Fullam, a fellow Ringsend man, had a quiet word saying “I know you’re nervous, just do your best”. A small gesture but one which stuck with Joe.

The match didn’t go so well for Brideville though, ending in dramatic and controversial circumstances. With the game entering the 90th minute and the score level at 0-0 it looked like a lucrative replay might be on the cards. Rovers had a late attack and a hopefully ball was lofted into the box. David “Babby” Byrne, the Rovers striker got in between Brideville’s Charlie Reid and goalkeeper Charlie O’Callaghan and leaping with all of his 5’5″ frame guided the ball into the goal with an outstretched arm. 56 years before the dimunitive Diego Maradona did it, the FAI Cup had its own Hand of God moment.

The game’s colourful, English referee Captain Albert Prince-Cox saw no infraction and blew for the final whistle shortly afterwards. Joe had been denied the Cup in his debut season in cruel circumstances. By the end of that season Joe had moved further back on the pitch and instead of playing outside right he had moved into the half back line and his favoured role.

Despite the disappointment of losing the 1930 final further success on the pitch was not far off. In May 1932, just weeks before his 21st birthday Joe O’Reilly made his debut in Amsterdam against the Netherlands. Things got even better when just twenty minutes in O’Reilly scored the game’s opening goal with a rasping, curling shot from the edge of the box, in the second half Paddy Moore, the man who had replaced Bob Fullam as the talismanic figure at Shamrock Rovers scored a second to give Ireland a comfortable 2-0 victory in front of a crowd estimated at 30,000.

That first game for Ireland was an important one in Joe’s career as directly afterwards he, Paddy Moore and Shamrock Rovers’ winger Jimmy Daly, who had also featured against the Netherlands were signed for Aberdeen manager Paddy Travers for the combined fee of just under £1,000. The British transfer record at the time was £10,900 paid by Arsenal for Bolton Wanderers David Jack back in 1928, so to get three internationals for under a grand can count as a canny bit of business by the former Celtic player Travers. Joe became a full-time pro and was paid the princely sum of £6 a week for his efforts.

To the Granite City and back to the Gate

Things started well in the granite city for Joe, he was a first team regular for much of the season, alongside his international teammate Moore. While Jimmy Daly made a mere four appearances before returning to Shamrock Rovers, Joe would make 26 appearances in all competitions that first season, while Moore started off spectacularly, scoring 27 goals in 29 league games (including a double hat-trick against Falkirk) to help Aberdeen to 6th place in the League in the 1932-33 season.

However, the following season would be less successful for both men, while Moore still scored a respectable 18 goals in 32 appearances his strike rate had decreased and he eventually ended up going AWOL after returning to Ireland for a match against Hungary in December 1934, blaming injury and a miscommunication with Aberdeen. It seems that Moore’s problematic relationship with alcohol was impacting his performances, to the point that manager Paddy Travers had effectively chaperoned him back to Dublin for an international match against Belgium. Whatever Travers did seemed to work as Paddy Moore would score all four goals in a 4-4 draw in that game.

Joe’s issues were more prosaic, he felt alone and deeply homesick in Aberdeen which affected his form, he also faced stiff competition for a starting berth from club captain Bob Fraser who often played in the same position at right-half. While he would technically remain on the Aberdeen books by the beginning of 1935 Joe O’Reilly had returned to Dublin and Brideville.

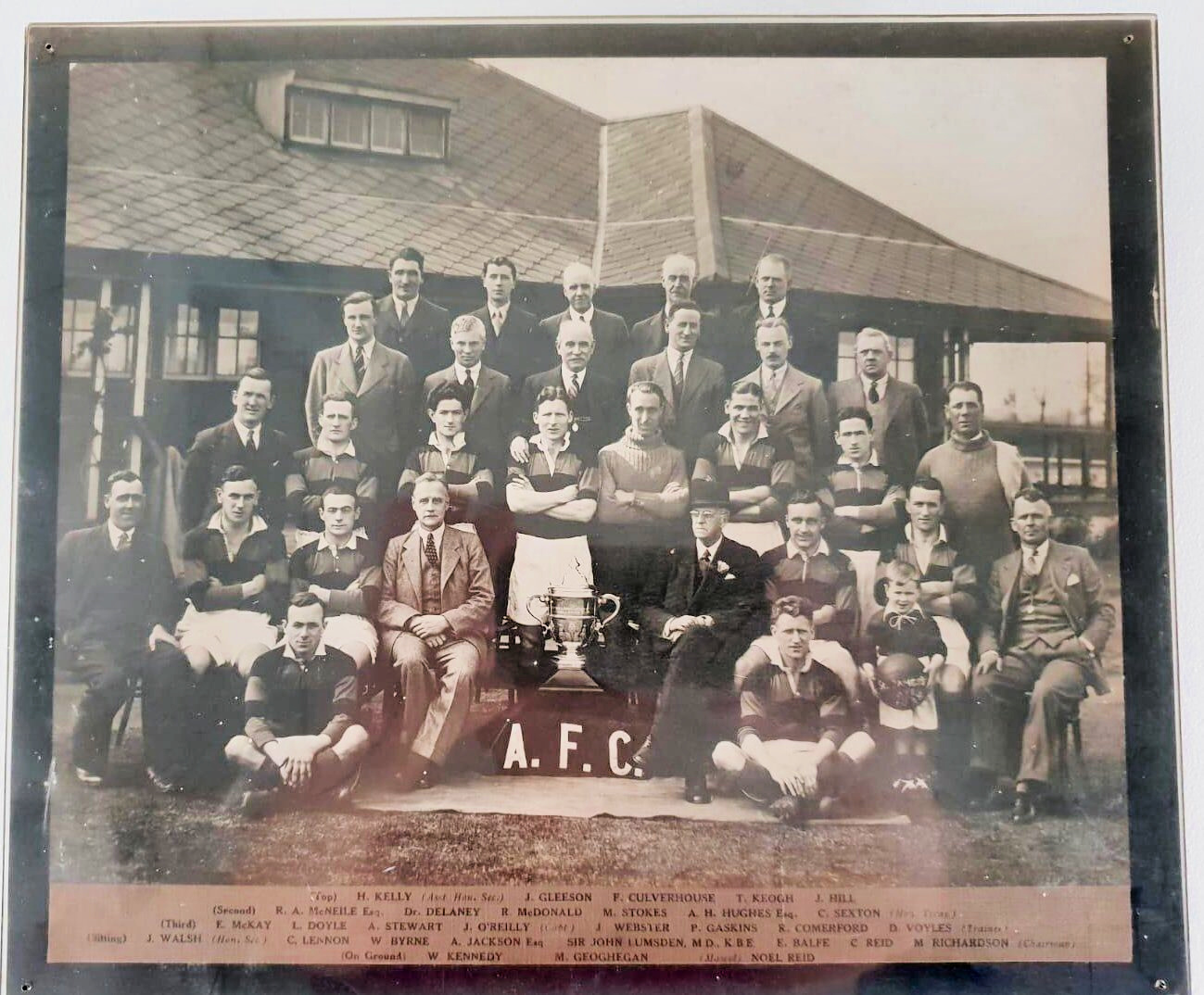

After a year with Brideville he relocated the short distance to the Iveagh Grounds to sign for St. James’s Gate and it would be with the Gate that Joe would enjoy his greatest success domestically. While his first season with the Guinness team was not hugely successful the 1936-37 showed significant promise. For one thing the side featured a versatile teenager by the name of Johnny Carey who would be spotted by Manchester United and go on to captain them to League and FA Cup success during his 17-year stint with the club. While Joe and Johnny would only spend a few months together in the Gate first team they would don the green of Ireland together on many occasions.

The season would also bring around another FAI Cup final for Joe O’Reilly, more mature now, with international experience under his belt, surely this would be different to that teenage cup final defeat against a heavily fancied Rovers side? Alas for Joe this wasn’t to be the case, it was Waterford who triumphed in the final 2-1, bringing the cup to the banks of the Suir for the first time thanks to goals from makeshift centre-forward Eugene Noonan (more accustomed to playing at right back) and Tim O’Keeffe, with the Gate’s Billy Merry scoring a consolation goal late on.

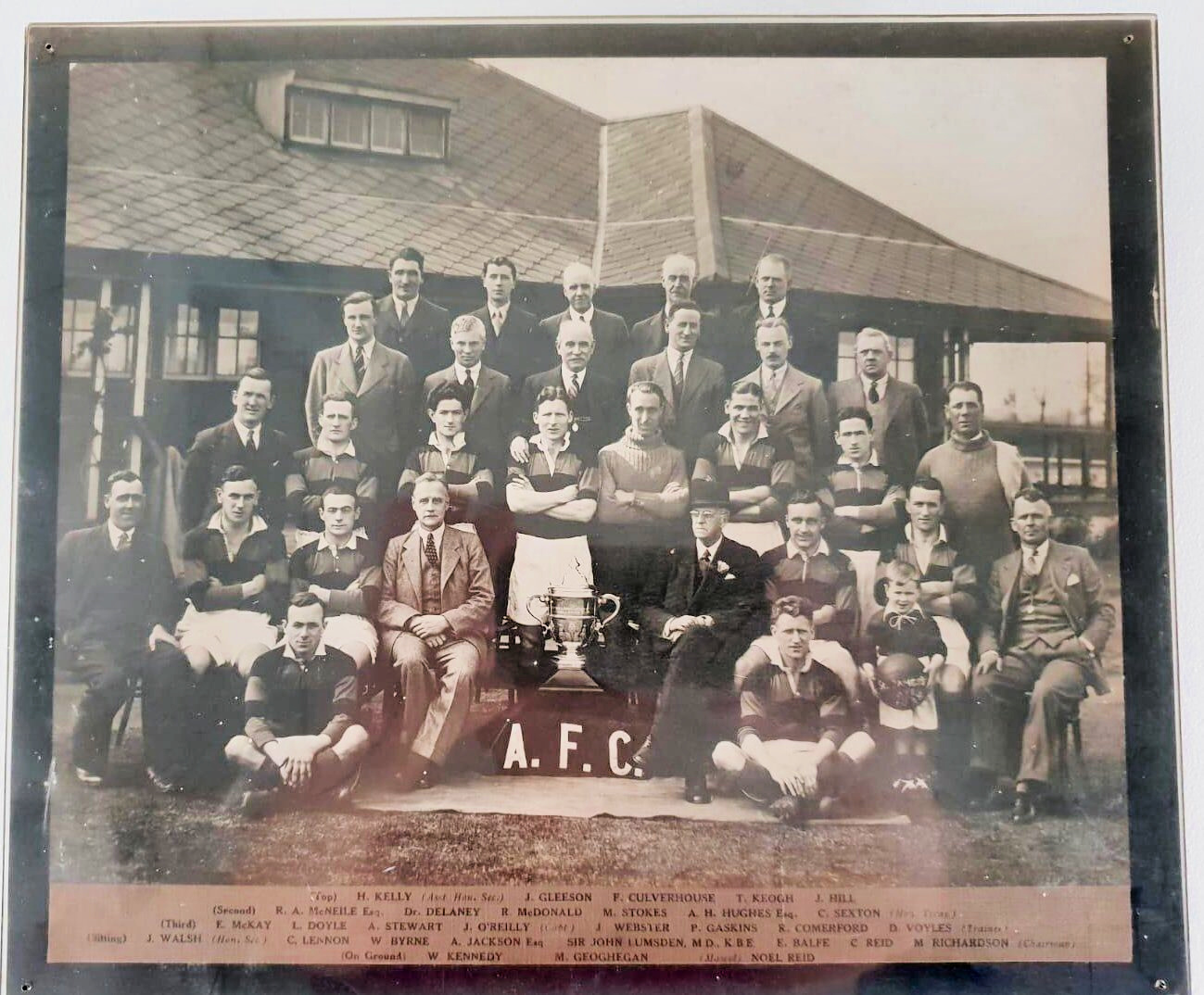

Two lost cup finals by the age of 25 – perhaps Joe thought he was cursed never to lift the trophy? But a year is a long time in football and 12 months later St. James’s Gate were back in the final again, and this time they would emerge triumphant, defeating Dundalk 2-1. Goals from Dickie Comerford and a second half peno from Irish international Peadar Gaskins sealing the win. Incidentally the consolation goal for Dundalk was scored by Alf Rigby, who had been a part of the St. James’s Gate side who lost the cup a year earlier, being on two different losing cup final teams, two years in a row is not a distinction that any player would enjoy.

That cup win in 1938 would mark itself out as an emerging high point in Joe’s career, not only had he won the cup, he had been the victorious captain, leading the Gate to their first win in 16 years. “A marvellous day and one I still treasure” recalled Joe in an Irish Independent interview decades later.

Joe standing behind the cup he had lifted in 1938 as team captain. (Credit Ger Sexton)

At international level Joe’s career was entering its prime. When he had made his debut in 1932 international opposition was difficult for the Irish team to find, near neighbours in Britain were refusing to play the national team in friendly matches for example. 1934 saw the first qualifying matches for the World Cup, Ireland were drawn in a group with the Netherlands and Belgium with Joe playing in both games.

The Belgium match entered the annals of Irish football history as one of the all time great international matches held in Dublin (and would perhaps set a national precedent for celebrating draws!) when Ireland drew 4-4. with Joe’s clubmate Paddy Moore scoring all four goals. The game against the Netherlands would be a disappointment however, despite taking the lead a late onslaught by the Dutch saw them run out 5-2 victors.

For the remaining five years Joe was pretty much an ever-present in the Irish team, playing a then record 17 consecutive international matches. He would score a second international goal in a 3-3 draw with Hungary in Budapest. Jimmy Dunne, also in record breaking form grabbed the other two.

A commemorative medal awarded to Joe after playing against Hungary in Budapest.

Joe also featured in both 1938 World Cup qualifying matches (home and away against Norway) however after a 3-2 defeat in Oslo a 3-3 draw in Dalymount wasn’t enough to get the side to France for the third installment of the tournament. Ultimately Joe’s international record read – played 20, won 8, lost 5, drew 7. This included some stand out victories over the likes of France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany.

The Germans

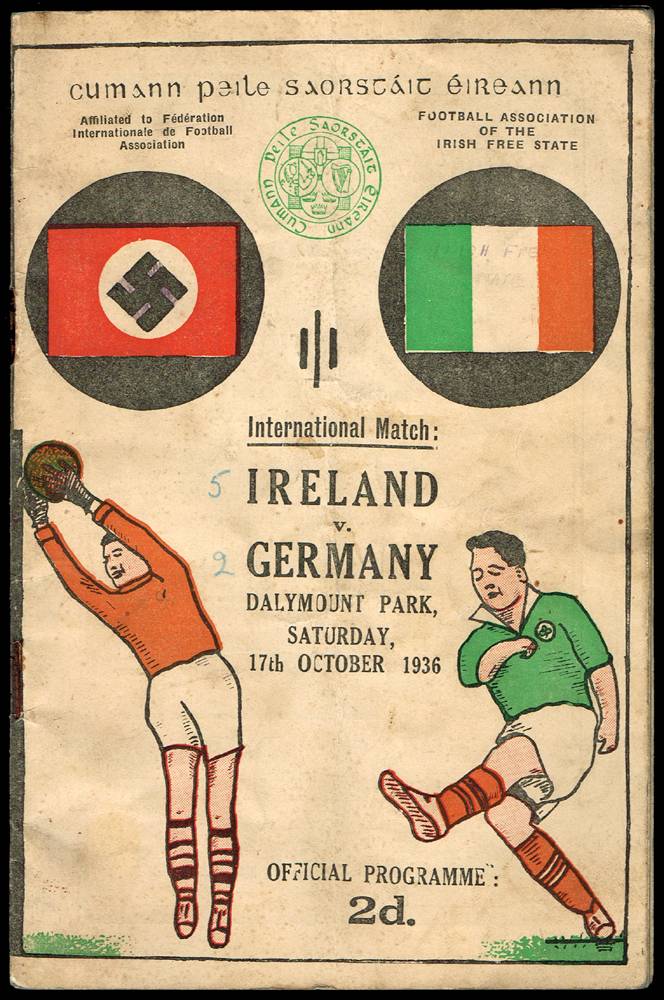

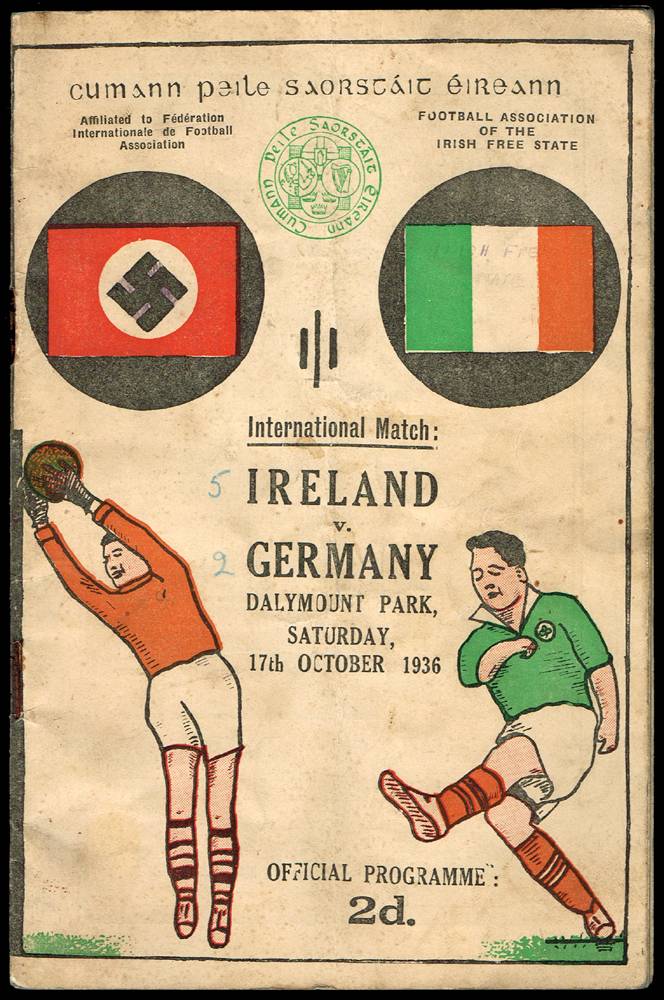

Two matches against Germany formed some of the clearest memories of Joe’s football career, which he discussed with both the Sunday World and Irish Independent many years later. The first of these matches took place in 1936 in Dalymount.

Infamous match programme from the 1936 game against Germany as presented for sale at Whyte’s auctioneers.

It was in this game that the German team, and over 400 German dignitaries gave the Nazi salute at Dalymount Park. Given the lens of history it is understandable that these events have tended to overshadow the team performance but it was something that shouldn’t be overlooked. The Irish side ran out 5-2 winners with Oldham’s Tom Davis scoring a brace on his debut, and Paddy Moore, slower, less mobile, but still perhaps the most skillful player on the pitch pulling the strings from the unusual position for him of inside left and creating three of the five goals.

This was something of an Indian Summer in Moore’s career (a strange thing to say about a man aged just 26), he was back at Rovers and was instrumental in helping the Hoops win the 1936 FAI Cup and he lit up Dalymount that day against Germany. It was his second last cap for Ireland, followed by an unispiring display in a 3-2 defeat to Hungary two months later. Injury and Moore’s well- documented problems with alcohol had, not for the last time, derailed a hugely promising football career. He finished his Ireland career with nine caps and seven goals.

Joe O’Reilly knew Paddy Moore well, from their time in Aberdeen, their outings together on the Irish national team and from facing him in the League of Ireland. When interviewed in the 1980s by journalist Seán Ryan, he said this of Moore;

He was a wonderful footballer, a wonderful personality. The George Best of his time… He was a very cute player. If, in a match, things weren’t going his way, he could produce the snap of genius to turn the match around – and he was always in the right spot. I had a good understanding with him.

Of that 5-2 win O’Reilly remembered it as the highlight of his playing career, telling Robert Reid in the Sunday World many year later;

The highlight for me was our 5-2 win against the Germans in 1936. Their ultra-nationalism acted as an incentive for us… what they weren’t going to do to us… and we beat them 5-2!

The second game against the Germans was even more controversial and took place three years later in May 1939, it would be the last international match played by the German national team before the outbreak of the Second World War. Similarly it would be the Irish team’s last international match until 1946. Of the eleven Irish players who took to the pitch in Bremen in 1939, only two, Johnny Carey and Kevin O’Flanagan would play for Ireland again.

The match was also a personal landmark for Joe O’Reilly as he became the first player to win 20 caps under the stewardship of the FAI. I’ve written previously on the details of that game in Bremen, the views of the FAI, and more widely about Ireland’s sporting relationship with Germany at this time. It was Joe’s recollections that however, provided one of the quotes that has endured, and it wasn’t even a direct quote from Joe, but rather his memories of Jimmy Dunne.

Dunne, who had never lost his socialist, Republican ideals, gave the Nazi salute under duress. As Joe recalled:

As we stood there with our right arm outstretched, Jimmy kept saying to me ‘Remember Aughrim. Remember 1916.’ By the time the anthem finished, I wasn’t quite sure who was more agitated the Germans or us.

As well as an interest in politics Dunne obviously seemed to have some interest in Irish history. O’Reilly recalls ahead of a game against Norway the usually laconic Dunne riled up his Irish teammates with references to Brian Boru’s victory over the Norse at the Battle of Clontarf. However, Dunne’s attitude in Germany stood in contrast with the official view of the FAI was recorded in the words of Association Secretary Joe Wickham. who said, “In Bremen our flags were flown though, of course, well outnumbered by the Swastika. We also, as a compliment, gave the German salute to their Anthem, standing to attention for our own. We were informed this would be much appreciated by their public which it undoubtedly was.” That the Irish athem was even played was in part down to Joe. On learning that the German band didn’t have the right sheet music Joe was able to write the notation to Amhrán na bhFiann from memory, thanks to his days in the Irish Army band.

Reflecting on his last cap more than 50 years later Joe felt the benefit of hindsight, appreciating things he perhaps didn’t as a sportsman in his 20s. He told Robert Reid;

But war was in the air. You could see it all around you, although you didn’t fully appreciate the extent of what was about to happen. How could anyone have known?

The anti-semetic feeling was already evident. But it was difficult to fathom what was really going on.

I remember the German soldiers. The shouts of “Heil Hitler” and the way we reciprocated their gesture. It was done in pure innocence. It just seemed like the thing to do at the time. I remember the young faces. I still remember them and wonder whatever happened to most of those young people, Germans, Jews, all the nationalities…

This match would be the last that Joseph O’Reilly played for his country, his international career ended, a week before his 28th birthday and three months before the Schleswig-Holstein battleship fired the first shots of World War Two.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Above are the panels on an international cap awarded by the FAI reprepsenting games that Joe O’Reilly played for Ireland in 1938 and 1939.

Epilogue

While Joe’s international career had come to a premature end his club career continued unabated. Unlike many European leagues the League of Ireland continued in as close to a normal capacity as was possible, during the years of the Second World War.

The 1939-40 season was to be one of great success for Joe as he captained St. James’s Gate to the league title. The men from the brewery finishing six points clear of nearest rivals Shamrock Rovers, while the Gate’s Paddy Bradshaw (who had scored in the 1-1 draw against Germany in Bremen) would end as the league’s top scorer with 29 goals.

Joe continued with the Gate until the 1943-44 season when the club disappointingly finished bottom of the league and failed to gain re-election, the club announcing that they were to revert to an amateur status thereafter. This wasn’t quite the end of Joe’s top flight career, as the club that replaced St. James’s Gate was his former side Brideville, returning to the League of Ireland after one of their periodic absences. Joe, now in his mid 30s signed on for one more season with the men from the Liberties before eventually hanging up his boots.

By this stage Joe had relocated to Saggart in south county Dublin and was working with Swiftbrook paper mills, a well established business who made official paper for the likes of the Irish Government, and according to historian Mervyn Ennis, James Connolly used the paper milled in Saggart for the publication of the Socialist Magazine, and when it came time to print it, the 1916 Proclamation. By this stage Joe had met and married his wife Helen and together they would eventually have six children; Geraldine, Helen, Maureen, Patricia, Bob and Brian.

Joe and Peter O’Reilly

Sport remained an interest throughout the family, from Joe’s father Michael, the physical education army man who later trained Kildare’s footballers for All-Ireland success in 1928, while his brother Peter who won an All-Ireland with Dublin in 1942. Even his son Bob made the Dublin GAA team league panel in the early 80s as well as playing soccer on the books of Shelbourne.

By all accounts a quite and humble man who preferred to amplify the achievements of others, Joe did gain some wider recognition later in life, being a recipient in 1991 of an Opel Hall of Fame award alongside Paddy Coad and Dundalk’s Joey Donnelly.

The Opel hall of fame award presented to Joe in 1991.

Joe passed away in October 1992 just a year after the receipt of this award. While he surprisingly remains little remembered in many Irish football circles he was one of the most talented and technically astute players for Ireland and an early international record breaker.

A special thank you to Bob O’Reilly for sharing memories of his father as well as many of the photos that feature in this article.

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory