From Love Street to Gartcosh in the year of ’86

By Fergus Dowd

In the bowels of the Celtic Park dressing room Daniel Fergus McGrain pinched the skin on his arm and inserted the needle in at a 45-degree angle, leaving the syringe in place for the prescribed five seconds.

Outside the Jungle swayed to the sounds of ‘Off to Dublin in the Green’ and ‘Roamin in the Gloamin’ as the Glasgow Old Firm prepared to welcome in 1986.

Sadly, there were no cameras to capture the atmosphere a dispute between television companies and the Scottish Football League resulted in no coverage of football in Scotland between September 1985 and March 1986. At the same time down south, English football also faced a TV blackout while then prime minister Margaret Thatcher proposed the demonising and draconian football ID scheme making it an imprisonable offence to attempt to attend a game without requisite identification.

Among the throngs that January day at Celtic Park was one Frank Bradley, he witnessed thirty-six-year-old McGrain, a diabetic, roll back the years in a man of the match performance as the Celts won out two to nil. Joe’s forefathers had left Co. Donegal and settled in Coatbridge nine miles from Glasgow, close by was the Gartcosh steelworks where his father and many relations had worked – the steelworks would put food on the table for many families in surrounding villages such as Glenboig, Muirhead and Moodiesburn.

With its origins in the Woodneuk Iron Works, which was established in 1865, Gartcosh was eventually turned into a cold reduction strip mill in 1962 by the time Joe’s father joined the payroll. Mr. Bradley and his colleagues would form the steel into flexible sheets that would be shaped into finished products such as automobile components or kitchen sinks.

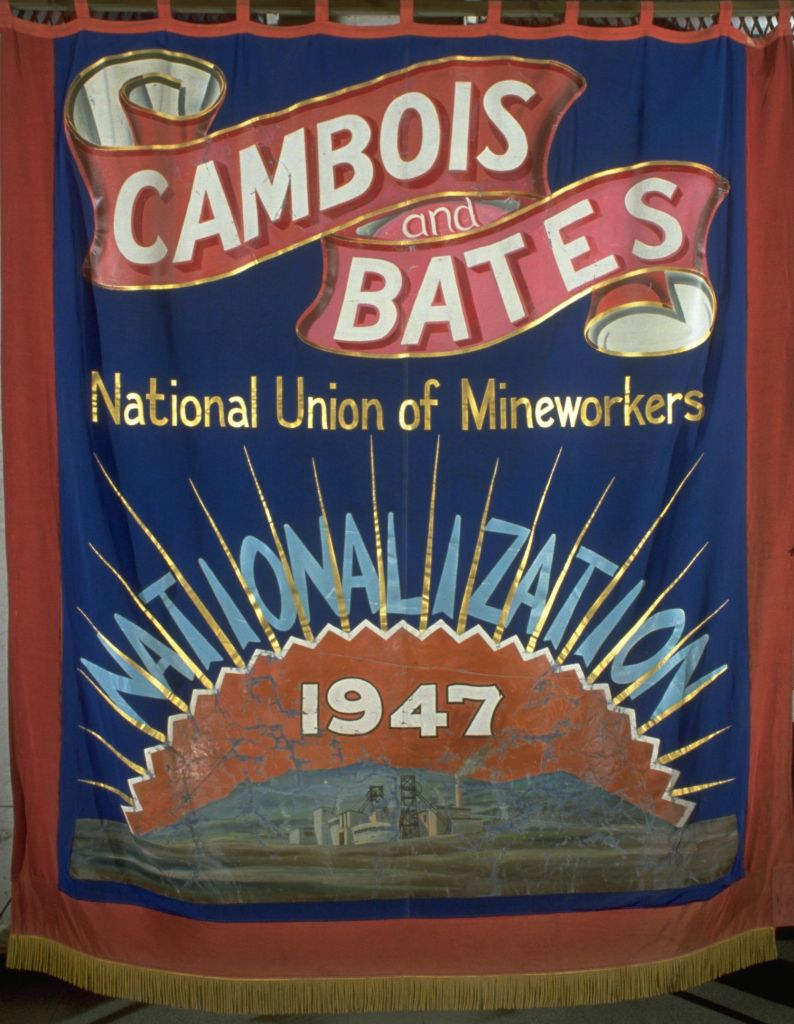

As Britain joined the European Union in 1973 opening up foreign competiton and the oil crisis plundered economies worldwide, the steel industry contracted. In 1979 as Mrs Thatcher was preaching St. Francis of Assisi on the steps of No. 10 thousands of Scottish steelworkers were wondering how they would support their families as employment in the industry detoriated from a high of twenty-five thousand plus to eighteen thousand a twenty-five per cent decline.

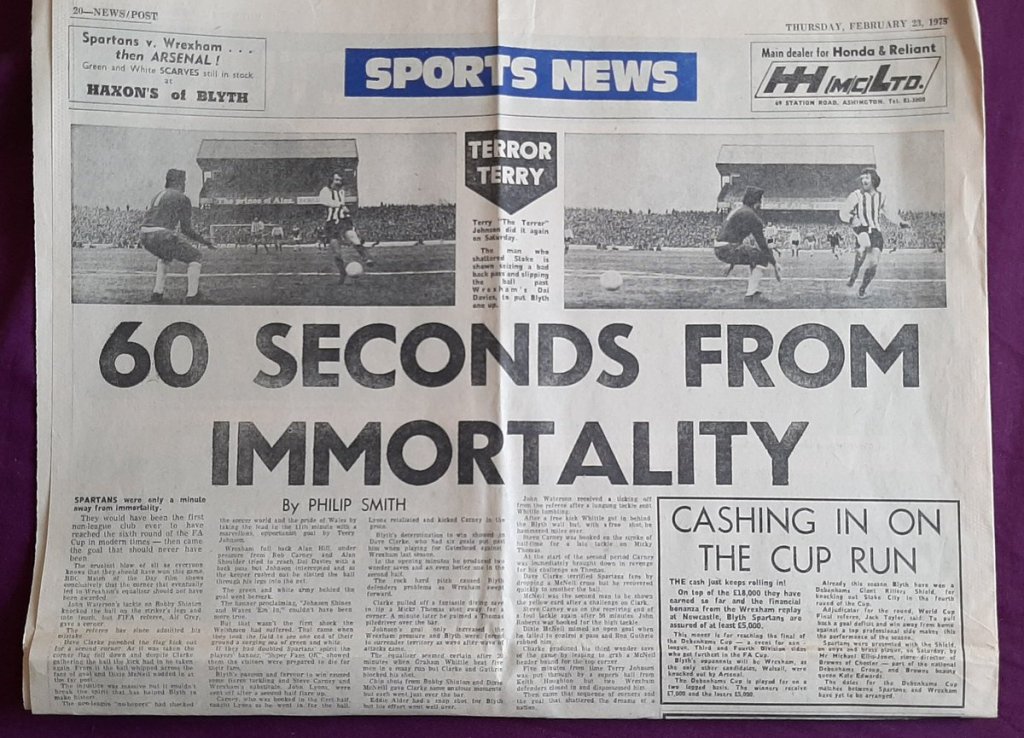

As Danny McGrain continued to tame Rangers main threat Davie Cooper filling in at left-back to accommodate Paul McStay’s brother Willie who played on the right for the New Year’s 1986 fixture – Tommy Brennan and colleagues were planning to march from Gartcosh to the House of Commons in London. They would leave on January 3rd in the snow performing relays to make London in ten days ahead of a House of Commons debate on the steel industry in Scotland; on the first night as they landed in Peebles the tempearture was minus 20.

The workers would successfully achieve their goal, however, on arrival at Downing Street they were greeted by Margaret Thatcher’s staff outlining the so-called Iron Lady was too busy to meet them.

Brennan would lead the men on the road for another mile as they handed their petition signed by twenty thousand Scots into the Queen’s aides at Buckingham Palace. Gartcosh the size of three football pitches would never open again and Ravenscraig steel works where Brennan worked would fold within six years.

Within twelve months of the march Hibs fans The Proclaimers would stand in Elstree Studios, London and sing about a ‘Letter from America’ and on the cover of the single for the world to see was Gartcosh.

For McGrain Scottish bigotry reared its head in stopping him joining his boyhood heroes Rangers his surname leading the local Ibrox scout to believe like Frank Bradley he was of Irish Catholic stock.

The McGrain’s lived in Finnieston an area made famous by the giant cantilever crane, which was like a beast in the skies, its primary purpose to lift tanks and steam locomotives onto ships for export.

Built of granite Daniel Fergus McGrain signed for Celtic in May 1967 twelve days before Jock Stein led eleven Glaswegians to immortality in Lisbon.

He would become part of the Quality Street gang of Dalglish, Hay, Connelly and Macari, his tough tackling and versatility would make him one of Scotlands greatest ever full backs. In those early years after making his bow at Tannadice against Dundee United in a League Cup fixture McGrain would have instant success as Celtic won the league in 1971 and 1972 – a fractured skull that season would put a slight dent in his progress. By 1974 as Celtic were on the cusp of winning nine league titles in a row, he was diagnosed with diabetes which for many can hinder their life never mind a sporting career.

The bearded one from Finnieston worked around his condition becoming a role model for others.

One of his finest hours came in 1979, as Margaret Thatcher was getting used to her new surroundings, McGrain was leading Celtic to a last day championship victory against the blue half of Glasgow. It was a Monday night, the 21st of May, again there were no cameras as a technician’s dispute meant the game would not be televised, a Celtic win would mean the league title. In an atmosphere you could cut with a knife Danny McGrain wore the captain’s armband in the same arm that he would inject to save him from disease and death.

Alex MacDonald silenced the Celtic faithful after nine minutes putting his name on the scoresheet, an instumental cog in Rangers Cup Winners Cup success of 1972 – by 1986 he would be manager of Heart of Midlothian and come within seven minutes of leading the Edinburgh side to a league title.

Ginger haired Johnny Doyle would seek retributon on MacDonald seeing red before half time, only two years later Celtic’s second son of Viewpark would be gone killed in an accident while rewiring his loft at home.

As the Celtic faithful sipped on their half time bovril the championship seemed destined for Ibrox, however, rallied by McGrain the ten men in green and white had other ideas. With an hour and six minutes on the clock Roy Aitken equalised and within another eight minutes bedlam ensued across two thirds of Parkhead as George McCluskey put McGrain’s men in the lead.

In a see-saw tie Bobby Russell equalised for Rangers sending twenty-five thousand blues into delirium believing again the domestic league trophy was headed across the city to Govan. Alas, with five minutes to play a McCluskey cross was cut out by the 6ft 4inch frame of Peter McCloy sadly for the Gers keeper he succeeded in only touching the ball onto the head of Colin Jackson who directed the ball into his own net – cue pandemonium around Celtic Park.

In the dying embers of the game midfielder Murdo McLeod scored the greatest Old Firm goal ever witnessed in the East End of Glasgow as he found the postage stamp of the Rangers goal with a strike sent from the heavens. As the Celtic faithful celebrated another title Daniel Fergus McGrain led his charges on a lap of honour around the famous hallowed turf as Rangers players lay all around him.

The New Years fixture of 1986 was a much straight forward affair for McGrain and Celtic and as Frank Bradley left the stadium for home his thoughts were of his neighbours, friends, and the imminent death of Lanarkshire’s most famous industry. It had only been nine months since Thatcher and her policies had crushed ‘the Enemy Within’ – mining communties across Britain with hundreds of years history were wiped out.

Within four months as Gartcosh lay empty, Alex MacDonald now manager of Hearts had created a team at Tynescastle that was on the cusp of the championship; moulded around Sandy Clark, Gary Mackay, and John Robertson. On the 3rd of May 1986 exactly sixteen weeks since Tommy Brennan had left for London Heart of Midlothian went to Dens Park while Celtic made the short trip to St. Mirren’s Love Street on the final day of the season – the TV cameras were back in situ. The mathematics were straightforward Hearts had to avoid defeat while Celtic needed a Dundee win and they needed to beat the budgies by 3 goals or more.

The men from Parkhead netted five times with Maurice Johnston, who would cross the religious divide of Glasgow, scoring one of Celtic’s greatest ever goals, while at Dens Park step forward Celtic fan Albert Kidd in the final seven minutes netting twice to break Jambo hearts.

In in his Lime green strip in the post match celebrations McGrain holds a bottle of champagne pouring it into the mouth of teammate Roy Aitken – McGrain had captured his ninth individual league title medal, it would be his last. Within one year nearly twenty years after he had walked through the doors of Celtic Park Danny McGrain was handed a free transfer; there was talk of a coaching role, but nothing materialised, it would be a decade before he would return.

In an interview thirty years after the march Tommy Brennan said about Britain’s first female prime minister:

‘So, for Mrs Thatcher I will say she brought the salmon back to the Clyde. By shutting the industries on either side of the river she cleaned it up. There you are.’

Where once Frank Bradley’s father and his relations earned their shillings today Gartcosh steel mill has been replaced by the police’s Scottish Crime Campus at a cost of £82million.

Thirty-two years after Love Street nearly to the day Daniel Fergus McGrain was found slumped in the driving seat of his car by police after going into hypoglycaemic shock – he survived – Celtic’s greatest number two still defying the odds.