At the beginning of the 1950’s the Hungarian international side were the great ascendant football team of the era, it was a period that would deliver them an Olympic Gold medal in 1952 and see them become runners-up in the 1954 World Cup in somewhat controversial circumstances as the West German national team pulled off on of the all-time sporting shocks.

Hungary’s international exploits were at somewhat of a remove from the League of Ireland where a Englishman, Welshman or Scotsman was usually as exotic as things got in terms of playing personnel, however the huge political changes that took place in post- War Hungary ended up having an unexpected, tangential impact on the League of Ireland as within ten years or each other two men, apparently Hungarian internationals, were lining up for League of Ireland clubs like Limerick City, Sligo Rovers and Drumcondra.

The first of these two was Siegfried Dobrowitsch who arrived in Ireland in 1949 via France after leaving his Hungarian homeland in 1947. Siegfried or “Dobro” and many of his Irish team-mates nicknamed him had left Hungary as the Hungarian Communist party were growing in power, becoming the dominant party in the short-lived Second Hungarian Republic before, in 1949, declaring Hungary a single party Communist state; the People’s Republic of Hungary.

Dobrowitsch claimed that he had heard about Sligo Rovers as part of a recruitment advertisement for new players brought to his attention by his French wife, not that far fetched when you consider only ten years earlier the club had persuaded an ageing “Dixie” Dean to sign up for a short stint in the north west. In fact the Sligo Champion newspaper went as far to lead with the headline announcing his signing with “First Dean, Now Dobrowitsch”.

Siegfried Dobrowitsch

In various reports it was stated that Dobrowitsch had been capped either five, or six times by the Hungarian national team and there was much comment about this being something of a coup for Sligo Rovers who were anxious to get him into their starting XI. However, Siegfried’s first game was delayed several times as Rovers had to seek international clearance for him to make his debut, there seemed to have been long, drawn-out correspondence with the French Football Association as Dobrowitsch had most recently been plying his trade for Strasbourg.

More information on Siegfried’s early life has come to light through the research of his daughter Alda Cornish, who recently visited Ireland and met with representatives of Sligo Rovers. In a piece in the Sligo Weekender where she filled in some scant details of her father’s early years, noting that “he was born in a part of what was Hungary and we understand he lost both of his parents by the age of seven. He was put in a Jesuit Boys Home, but it was a very cruel place where he grew up. The next thing I could find was he was playing football and working as an electrician. He ended up in France around 1947 and played with Strasbourg, where he met his first wife.”

Newspaper reports at the time state that Dobrowitsch was born in a part of Yugoslavia that had come under Hungarian control and that his multi-lingual French wife acted as his interpreter. In an interview published in February 1949 in the Irish Independent, presumably with his wife acting as translator Siegfried got to explain something of his personal story. Born around 1920 he claimed to have won six international caps for Hungary between 1938 and 1942, after which point he was drafted into the Hungarian army to fight for the Axis powers during the Second World War.

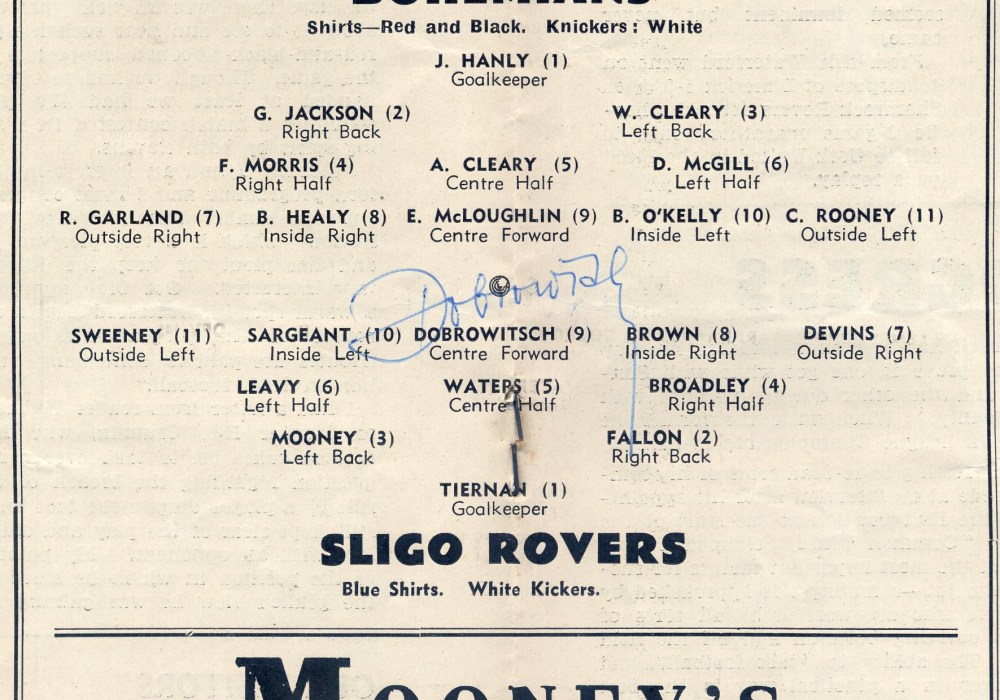

After his army discharge in 1946 he returned to his farm before it was seized by the government the following year, fleeing across the country he was assisted in crossing into Austria and from there into France, where he met his wife and eventually relocated to Dublin, commuting to Sligo with the club’s other Dublin-based players and using Dalymount Park as a personal training ground. He was even in the stands at Dalymount, awaiting his international clearance when Sligo met Bohemians in early March 1949, going so far to sign a match programme for a star-struck fan, obviously impressed by the presence of a supposed Hungarian international. (You can see his signature in the header image of this article).

His international clearance eventually arrived and on March 27th, over a month after his signing was initially publicised Siegfried Dobrowitsch made his debut for Sligo Rovers in a 1-1 draw with Limerick in the Showgrounds. While the reports describe a tight game where Dobrowitsch, the starting centre-forward had to survive on scraps, he did manage to score Sligo’s only goal of the game, a well dispatched, powerful penalty kick early in the second half.

Despite a good start there was misfortune only a couple of weeks later when Dobrowitsch was involved in a car crash on his way from Dublin to a match in Sligo. Travelling up for a match against a Sligo local league selection, Dobrowitsch, along with goalkeeper Fred Kiernan and winger Stephen Leavey crashed into another vehicle. While luckily nobody was seriously injured Siegfried did suffer a dislocated shoulder and missed a number of games as a result.

Perhaps as a result of his injury, work commitments in Dublin, or merely through inconsistent form Dobrowitch’s stay in Sligo was relatively short-lived, by November of 1949 he had been released by Sligo despite boasting a relatively successful strike rate and had been signed by Drumcondra in Dublin.

Things started relatively well for Siegfried at Drums, scoring twice on his debut against Shelbourne in a Shield game which Drumcondra won 4-1. Despite this initial success only a year later Seigfried had dropped out of senior football and was lining out for Larkhill in the AUL.

When interviewed many years later Dobrowitsch’s former teammate Pa Daly recalled playing alongside him. While he was referred to as “Dobro” when in Sligo the Drumcondra players had instead dubbed him “drop-a-stritch”, and in Daly’s opinion Dobrowitsch had never been a Hungarian international as they had been led to believe. While he praised Siegfreid for his dedication to training, recalling the exasperated Drums groundsman Peter Penrose calling in Dobrowitsch from training with the words “come on in or the pubs will be closed!” he was of the opinion that his claims to have been a Hungarian international were exaggerated. Any research in relation to the matches that Siegfried Dobrowitsch claimed to have played in for Hungary show no similar names on the historic teamsheets. Ultimately Siegfried would leave Ireland around 1956 bound for Zimbabwe where he spent much of the remainder of his life before he passed away in 1994.

More recently, research by Hungarian sports writer Gergely Marosi has suggested that these details may actually refer to the life and career of Andor Dobrovics, who seemed to be from the town of Rákosszentmihály and played for his locaL club, RAFC who were a lower tier club. He played as a midfielder and occasionally a forward before he moved to top-flight side Elektromos for a short stay. Dobrovics never played for the first team, mostly lining out for their reserve side.

While the story of Seigfried Dobrowitsch may seem unusual he was just the first supposed Hungarian international footballer to play in the League of Ireland in the 1950s. The second was Laszlo Lipot who enjoyed a brief spell at Limerick after arriving in Ireland as a refugee around the time that Seigfried Dobrowitsch was leaving Ireland. Lipot, who lined out at right half for a short time with Limerick in 1956-57 had ended up as one of a small group of refugees taken in by Ireland after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was crushed by the state authorities with the backing of the Soviet Union.

What had begun as a series of protests in Budapest in October 1956, mostly from students, journalists and writers seeking reform of the system of government, and a move away from the influence of Moscow quickly turned violent, the Hungarian government sought military support from the Soviet Union which was speedily dispatched. The revolutionaries stood little chance against the might of the Soviet military. The newly installed Hungarian government quickly carried out mass-arrests numbering in the tens of thousands, it was estimated that upwards of 200,000 refugees fled Hungary in the aftermath of the failed revolution and among their number was Laszlo Lipot.

Of the thousands who fled Hungary more than 300 refugees found themselves in the far from glamourous surroundings of the Knockalisheen army camp just outside of Limerick City on the far side of the Clare border. While the refugees were broadly welcomed by the local people life in the army camp was tough and there was even a threatened hunger strike by some of the refugees at the conditions they endured.

Laszlo Lipot is first mentioned in December of 1956, less than two months after the Hungarian Uprising had been suppressed. In the December 8th edition of the Limerick Leader there is a cryptic reference to Lipot under the pseudonym “Janos” who is described as a Hungarian international right back who had only recently represented the national team against Czechoslovakia and had been an international teammate of no less a luminary than Ferenc Puskás. It states that “Janos” has been training with Limerick and had impressed the team management and was hopeful of making his first team debut in the near future. He did make his debut shortly afterwards, in a game against Shelbourne, which ended in a heavy 6-1 defeat, though match reports say that Lipot/Janos was one of the better Limerick players on the pitch. He was unable to add to this single start as his playing registration still lay with the Hungarian FA.

Newspaper reports named his club as “Tata” which according to Hungarian football expert Gergely Marosi was a reference to Hungarian club Tatai Vörös Meteor SK who have since merged into umbrella club Tatai AC. This would mean however, that he certainly was never an international as his club would have been in the third tier at the time. The closest he would have ever come to this standard was playing for his county in inter-region exhibition matches so the talk of an “international” seems to be another tall tale.

Back in Limerick it would be August 1957 before he would get to play another game for the Shannonsiders when the issues with his playing registration were finally resolved, and he was able to line out for Limerick under his own name of Lazslo Lipot. His Limerick career was shortlived however as by the end of the summer of 1957 most of the few hundred Hungarians who had been living in the Knockalisheen camp had left the country, many left to start new lives in Canada and the United States while Laszlo and his wife took the shorter journey to England in September of 1957. His Limerick playing career had amounted to a single league game against Shelbourne in the 1956-57 season and a handful of Shield games in August and September of 1957.

What exactly became of Laszlo after he left Ireland is something that I’ve been unable to find out, there is a death notice for a Laszlo Lipot in the town of Caerphilly in South Wales from 2004. This Laszlo had been born in 1931 and would be the correct age, perhaps he was the same man who once graced the Markets Field?

The cases of Seigfried Dobrowitsch and Laszlo Lipot are striking in their similarity, both were refugees from the post-War turmoil that engulfed Hungary, in Dobrowitsch’s case as an orphaned former soldier he claimed to have fled after the loss of his farm to the new emerging Communist rulers in the late 1940’s, for Laszlo it was the violent events of the 1956 Uprising that led him to leave his homeland. Whether he had been directly involved and feared reprisal or simply wanted to escape a harsher regime after the direct military intervention of the Soviet Union that spurred him to leave we simply don’t know.

We do know however, that both men had some talent for football, and in the days before Youtube highlights videos and professional scouting software both men were able to embellish their playing careers, adding international caps that almost certainly never existed to their playing CVs. While neither player had the longest or most successful League of Ireland career they are examples of a subgroup rarely mentioned in Irish football or indeed, Irish society, namely political and economic migrants who came to Ireland to make a better life. While we might think this is a recent phenomenon the stories of Siegfried and Laszlo shows that is dates back decades. It also shows that we perhaps haven’t learned from the mistakes of the past, while several of Laszlo’s fellow refugees in Knockalisheen did remain in Ireland and built new lives the majority left after less than a year in Ireland, often after protests and threatened hunger strikes about the poor quality of their accommodation. Today Knockalisheen is used as a Direct Provision Centre.

With both men there are many unanswered questions about their lives and careers, especially back in their native Hungary, if any readers have any further information I’d hope they would get in touch so that I can better separate the truth for the stories told about them.

Programme image provided by Stephen Burke. If you enjoyed this article you may also find this piece on the life, career and tragic death of Hungarian international Sandor Szucs of interest.