Shutting the open door – when the League of Ireland tried to poach Britain’s best

Jock Dodds was a larger than life character, a man known to swan around Depression era Sheffield in an open-top Cadillac, wearing a silk scarf and fedora hat, a man who ran greyhounds (and casinos) among an impressive number of side-projects, he was also one of the most powerful, dashing and effective centre-forwards of his era, though his prime years were robbed by the outbreak of the Second World War. Dodds’ extrovert personality and determination to make a buck often brought him into conflict with the powers that be, one such occassion led to him spending a short but significant spell in Dublin, and in the process changing the sporting relationship between Ireland, Britain and FIFA.

Ephraim “Jock” Dodds (pictured above) was born in Grangemouth, Scotland in 1915, his father died when he was just two years of age and he moved with his mother to Durham, England when she remarried in 1927. Jock, the name he was known by for the rest of his long life was a particularly unoriginal nickname due to he Scottish birth and upbringing.

As a teenager he was signed up by Huddersfield Town but it wasn’t until he joined Second Division Sheffield United in 1934 that he enjoyed an extended run as a first team player. United had just been relegated from the top flight and had lost their top scorer, Irish international Jimmy Dunne, to league winners Arsenal the previous season, Dodds, not yet 20 had big boots to fill but he enjoyed an impressive debut season for the Blades, scoring 19 goals in 30 matches. His good form and scoring touch for United continued over the following four seasons, to the point that in March 1939, Blackpool, then in the top flight, spent £10,000 to bring Dodds out to the coast. The fact that this represented the second-highest fee ever paid for a player in British football, (just behind the £14,000 price that Arsenal had paid Wolves for Welsh international Bryn Jones), shows just how highly rated Dodds was at the time.

Dodds was an immediate success at Blackpool, scoring 13 goals in his opening 15 games, but on the 3rd September 1939, just days before Dodds’ 24th birthday, Britain declared War on Germany after the latter’s invasion of Poland. League football was immediately suspended. During the War Dodds was employed by the RAF as a drill sergeant and physical training instructor in the Blackpool area, spending most of his time working from a repurposed Pontin’s holiday camp. Dodds continued playing for Blackpool during the Wartime Leagues and also featured eight times for Scotland in Wartime internationals, including scoring a hat-trick in front of over 90,000 fans in a 5-4 victory over England

The 1946-47 season represented a return to the traditional English football calendar after the Wartime suspensions and Blackpool and Dodds were gettting ready for a return to the top-flight. Almost 31 years of age at the beginning of the season Dodds had starred for Blackpool and Scotland during the War and was surely hopeful of continuing his career with the resumption of League football. However, Dodds was quickly at loggerheads with the Blackpool hierarchy who only offered him £8 a week if he was dropped to the second team but the maximum wage of £10 if he played for the first team. Other reports suggest he was offered even less than the maximum wage. Dodds felt slighted, as a star of the Blackpool side during the War years, that regularly played to home crowds of 30,000 he thought he was worth more and refused to sign. He was placed on the transfer list at the stated price of £8,000.

With Dodds transfer listed, it was reported that Liverpool and Nottingham Forest were among the clubs interest in signing him. At this point it is worth giving some further explanation of player registration and transfer arrangements at the time. Jock Dodds was out of contract with Blackpool. In today’s game this would make him a free agent an allow him to sign for the club of his choosing. However, this was not the case in 1946 when clubs held far greater sway, and as Blackpool were the club who held the player’s registration Dodds could not move to another club without their cooperation in transferring this registration to the new club. This meant that Dodds was on the so-called “retained list” , a player out of contract but with the club keeping their registration as they viewed the player as being worth a transfer fee. This system was recognised throughout Britain and Northern Ireland, but importantly not in the Irish Free State.

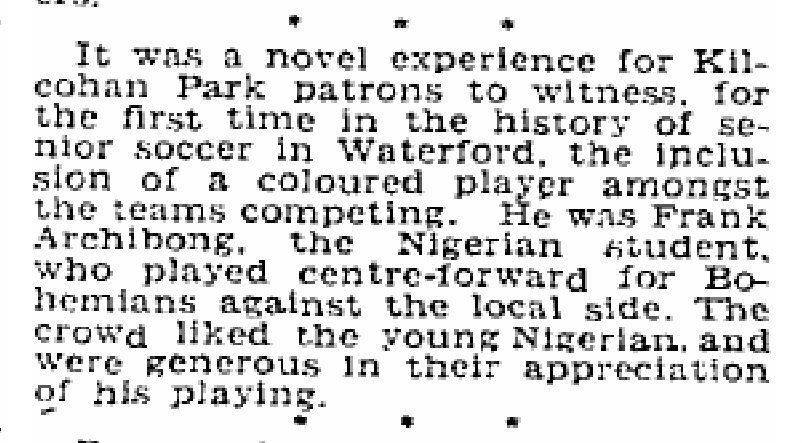

This arrangement had usually benefitted clubs in Britain and Northern Ireland where players on the “retained list” of League of Ireland clubs were signed up without a transfer fee changing hands. In several cases clubs in Northern Ireland signed players from the League of Ireland for nothing but sold them on to English or Scottish side for a sizeable profit after short periods. The process could of course also work in reverse, League of Ireland clubs could sign players of sigificance for nothing from British clubs. This policy was popularly known as “The Open door” and was something that League of Ireland clubs exploited especially in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War.

Shamrock Rovers and Shelbourne in particular were keen to sign up well known players from British clubs retained lists in these immediate post war years. Rovers had experienced a disappointing 1945-46 season, finishing 4th in the league and losing the FAI Cup final to Drumcondra, several of their star players had also departed, Davy Cochrane and Jimmy McAlinden – both capped by the IFA, returned to England on the resumption of post-War football, rejoining Leeds United and Portsmouth respectively, and the Cunningham family sought to recruit some big-name players who would generate an increase in crowd numbers and have Rovers back in contention for honours.

Rovers’ historian Robert Goggins notes in his history of the club that Hoops players would have been earning in or around £2 a week at this time, but the Cunninghams were prepared to go far beyond this level to attract prominent players from the other side of the Irish Sea. First of all they signed Tommy Breen, Manchester United’s Irish international goalkeeper through the “open door” system. Not to be outdone, rivals Shelbourne signed Manchester United’s other goalkeeper, Norman Tapken as well as former Liverpool and Chelsea forward Alf Hanson who finished as Shels top scorer that season.

Rovers then turned their attention to Jock Dodds who was reportedly offered £20 a week and a signing on fee of £750. Huge money at the time but considering Blackpool were looking for a transfer fee of £8,000 still something of a bargain. Despite the objections of the Blackpool Chairman, Colonel William Parkinson there was no stopping Dodds who remarked,

Whatever happens I shall fly to Dublin a week from now, I intend to see it all through to the end.

The Blackpool chairman complained that the movement of footballers to Ireland was an “absurd traffic” and expressed concern that he and other clubs could continue losing out on significant transfer fees if the situation continued.

While Parkinson was understandably concerned about losing one of his best players who he valued at £8,000, for nothing it was a bit rich hearing this coming from a senior figure in British football. The “open door” of course swung both ways, and the wealthier clubs in Britain and indeed Northern Ireland exploited it readily when it suited them to sign players without paying a transfer fee, from clubs in the League of Ireland. The Shamrock Rovers chairman Joe Cunningham was quick to point this out when pressed on the issue. The Irish Independent’s football columnist W.P. Murphy went further and listed several players who had been signed from League of Ireland clubs by sides in England or Northern Ireland without a fee being paid, the most recent case cited was that of Eddie Gannon. Rated as one of the best half-backs in the league, the 25 year old Gannon had been signed for nothing by Notts County from Shelbourne earlier in 1946.

Gannon would make over 100 appearances for County and become a regular for Ireland before being signed by Sheffield Wednesday for £15,000 (a massive fee at the time) less than three years later. Shelbourne would be right to have been aggreived as this would have been a record transfer fee for an Irish player yet the Dublin club saw none of it. As mentioned, clubs in Northern Ireland also did well from these arrangements, in those immediate post war years players of the calibre of Thomas “Bud” Aherne (Limerick to Belfast Celtic) Con Martin (Drumcondra to Glentoran) Robin Lawlor (Drumcondra to Belfast Celtic) and Noel Kelly (Shamrock Rovers to Glentoran) all moved north of the border without fees being paid, in many cases these players later moved on to clubs in England for significant sums.

On the pitch the signing of Dodds by Shamrock Rovers had the desired impact, on September 8th 1946 he scored twice on his debut, a 2-2 draw with Drumcondra in a City Cup game. He also paid back part of his sizeable wages and signing on fee, Milltown was packed for the match, the crowd was estimated at 20,000 and many of them there to catch a glimpse of the dashing Dodds. Rovers lost their next City Cup game against Shelbourne 2-1 which effectively ended their challenge for that trophy, although Dodds was once again on the scoresheet and proved a star attraction; Shelbourne Park had recorded its highest gate receipts in fifteen years, totalling £718.

There were reports that Rovers were looking to add to their star names with new cross-channel signings to further boost their gates and improve on some indifferent performances. Among the names mentioned were Stanley Matthew, who was in dispute with his club Stoke at the time, as well as Peter Doherty, one of the great inside-forwards of his era and someone that Rovers tried to sign on more than one occasion, he had fallen out with the directors of Derby County after they objected to his taking over the running of a hotel. Neither deal would materialise in the end but the move of Dodds to Rovers, and to a lesser extent the signings made by Shelbourne were a significant point of controversy. It brought the issue of the maximum wage (then capped at £10 per week) into the pages of the press, with columnists asking if it were not reasonable for a top player, whose presence alone could add thousands to attendance figures and hundreds of pounds to ticket takings, to be paid a higher amount? The Reveille newspaper was moved to write the following on the Dodds transfer;

Unless some satisfactory agreement is reached before very long on the question of a player’s wage, I forsee one of two one or two other prominent stars crossing to Eire

Dodds time with Rovers was to be relatively short-lived, Blackpool had complained to the FA about the situation, and the FA in turn complained to FIFA, an organisation that they had just re-joined after one of their periodic absences. The Britsh press reported that Dodds had even approached the Blackpool Chairman, William Parkinson in late October stating that he had made an “unwise move” and wished to return to England. In all Dodds would only play in five games for Rovers scoring four goals over the course of just over six weeks. This included two games in the City Cup and three in the League of Ireland Shield. Dodds would ultimately join Everton at the beginning of November 1946, having signed off for Rovers with another goal against Drumcondra just days earlier. The agreed fee would be £8,250 between Everton and Blackpool although the Irish Independent reported that some payment was made to Rovers by Everton as they recognised the contract Dodds had with them, and that this was crucial to Everton getting in ahead of Sheffield Wednesday in the bidding war. The minute books of Everton confirm that Rovers did receive payment in the amount of £550 which Everton noted that they felt “was not obligatory” but that there was “a moral responsibility in ratifying the payment”.

This idea that Rovers would have received financial compensation is slightly surprising, along with Dodds desire to return to England, the FAI had also apparently received a letter from FIFA seeking a resolution to the “open door” system. Before the month was out a conference was arranged in Glasgow to regularise transfer arrangements, delegates from the League of Ireland and representatives of the Scottish and English Leagues were present and on the 27th November Jim Brennan, secretary of the League of Ireland was in a position to telegram Dublin to advise that “full and harmonious agreement was reached for the mutual recognition of retained and transfer lists” – the open door had finally closed. The following month the Irish Football League met and agreed that they would also abide by the Glasgow agreement which ceased the practice of the major Belfast clubs signing players from south of the border without fees being paid.

Dodds would go on to have a productive couple of seasons for Everton before moving on again, this time to Lincoln City for a fee of £6,000 in 1948. He continued to find the back of the net for the Imps before finally hanging up his boots in 1950, aged 35. He did however, have one more brush with officialdom over the breaking of contracts and transfers abroad. In 1949, a Colombian football association called DIMAYOR had broken away from FIFA following a dispute with an amateur football association, as a result this association was banned by FIFA but an independent Colombian league offering huges salaries to entice the best players from abroad was formed. Nicknamed “El Dorado” due to the wealth on offer, the league’s clubs signed the likes of Alfredo Di Stefano from River Plate but were also keen on British professionals and ended up enticing top players like Manchester United’s Charlie Mitten and Stoke City’s Neil Franklin to Bogotá. Jock Dodds was also in the mix, acting as a recruiter and go-between for the Colombian league, and getting a cut for himself of course. Dodds ended up being banned by the Football Association in July 1950 for bringing the game into disrepute for his role in the “Bogotá bandits” affair, but was later cleared.

As for the League of Ireland, well it was a qualified victory, Hanson, Tapken et al would leave Shelbourne after a successful season and return to England. Tommy Breen left Shamrock Rovers, moving to Glentoran for a fee of £600, though this was paid to Manchester United, the club that held his registration. The fears of the British press, that big money contracts could entice the cream of their footballing talent across the Irish sea without a transfer fee never materialised, nor where they likely to. Astute businesspeople like Joe and Mary Jane Cunningham at Shamrock Rovers saw the benefit of offering big money to the likes of Dodds to come to Milltown. For the £900 or so they invested in his signing on fee and wages they probably made as much back in increases to gate receipts generated by his presence in the team and seem to have made at least some money out of the Everton transfer. Such signings and wages were not sustainable overall and can be seen as part of an ongoing pattern of League of Ireland sides signing up big name players (usually coming towards the end of their careers) on short term contracts to boost crowd numbers and generate interest and media coverage for the club. The likes of George Best, Bobby Charlton, Geoff Hurst, Gordon Banks and even Uwe Seeler would appear in the League of Ireland for a handful of games in the decades to come, and usually ended up putting extra bums on seats, at least in the short term.

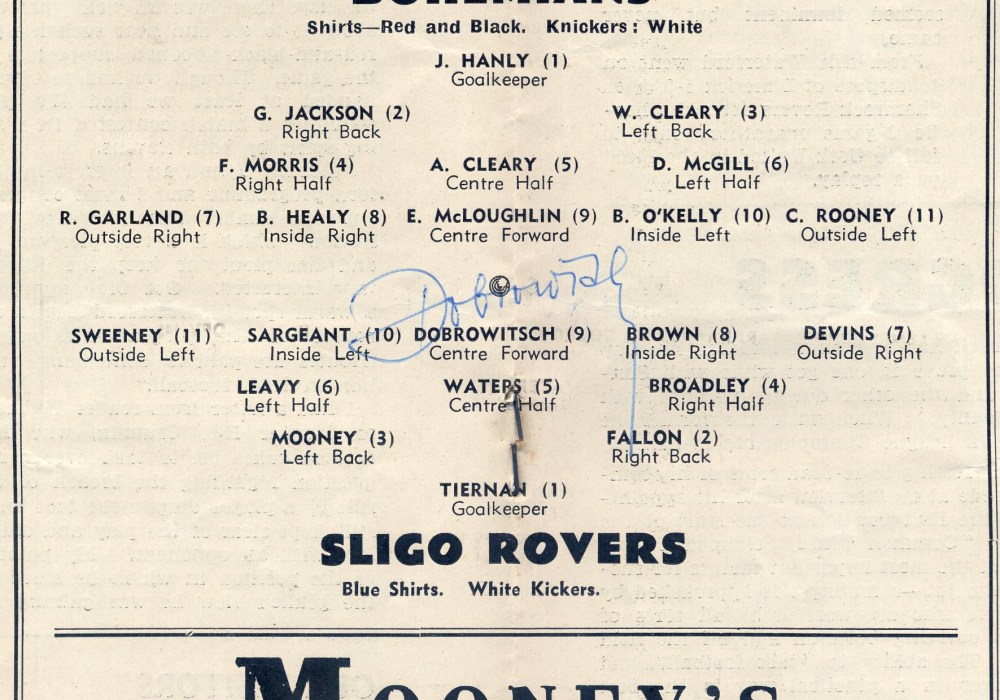

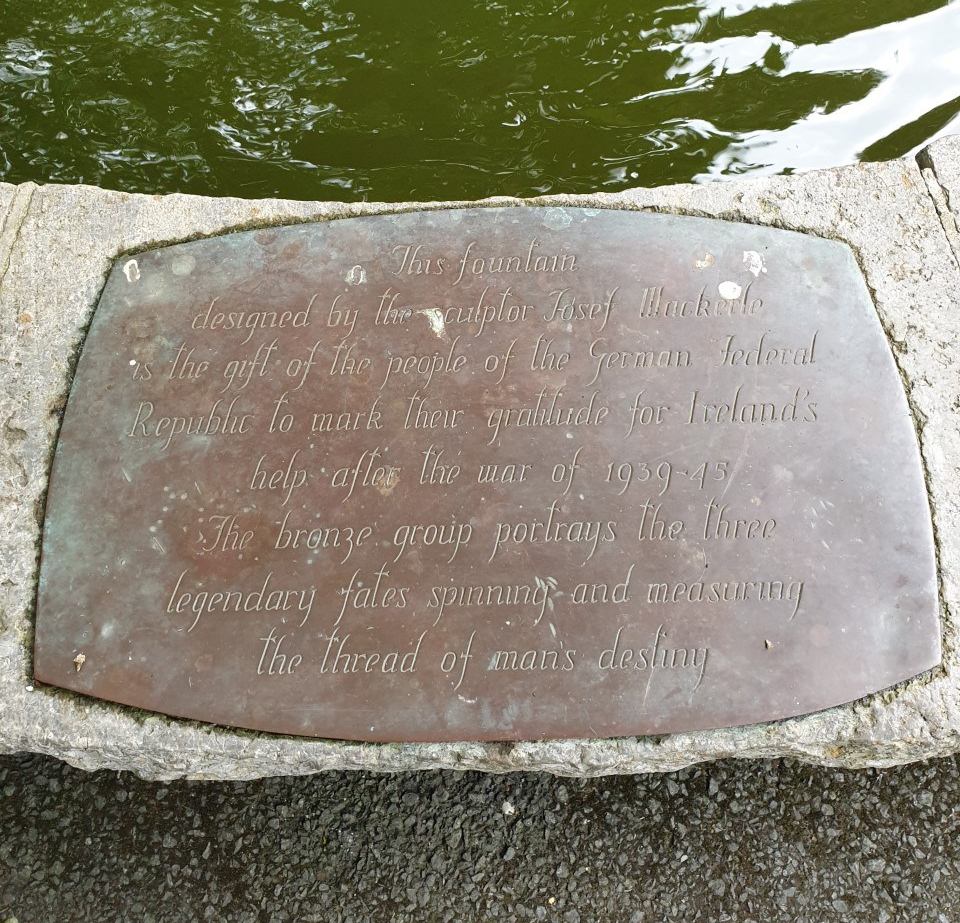

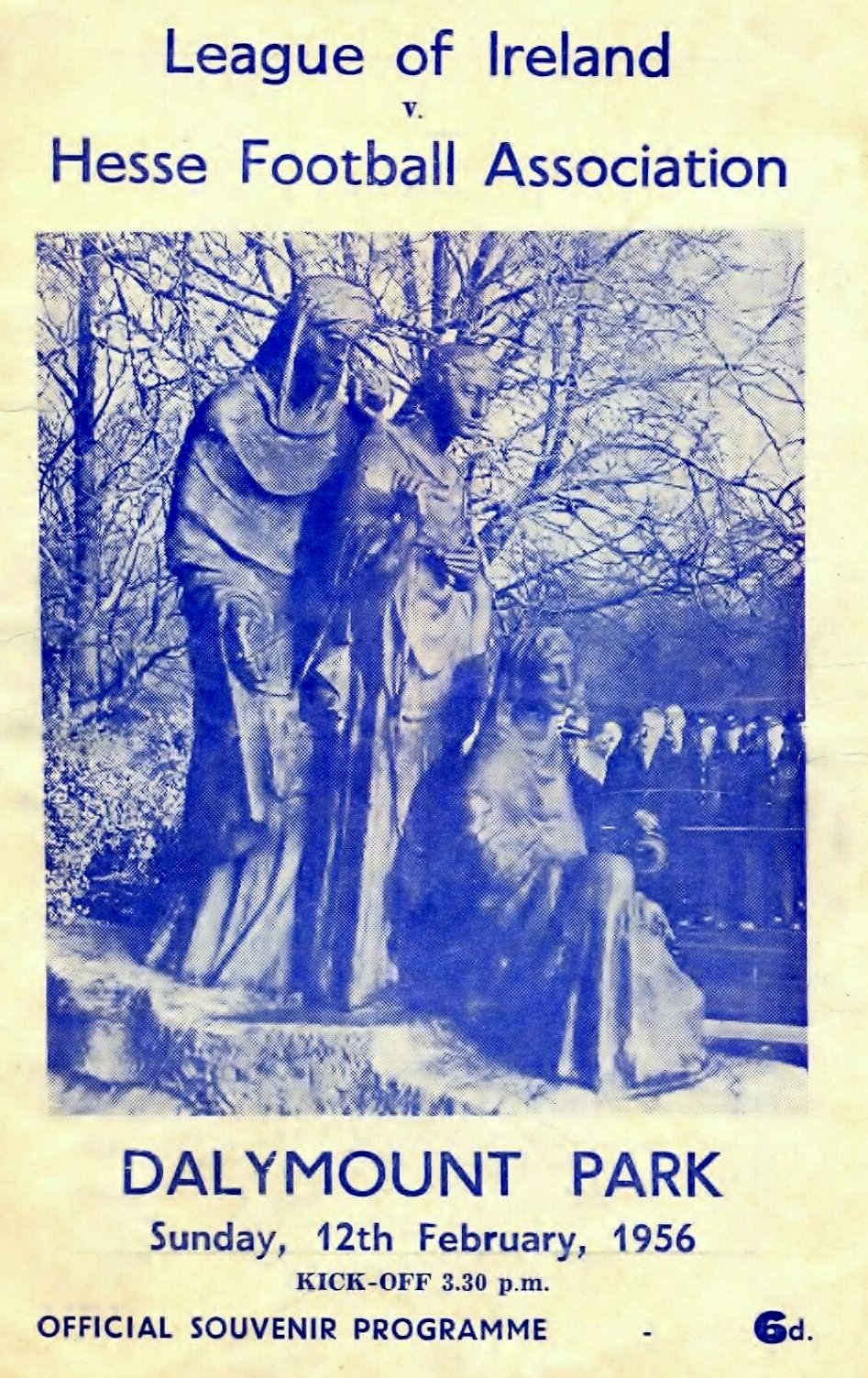

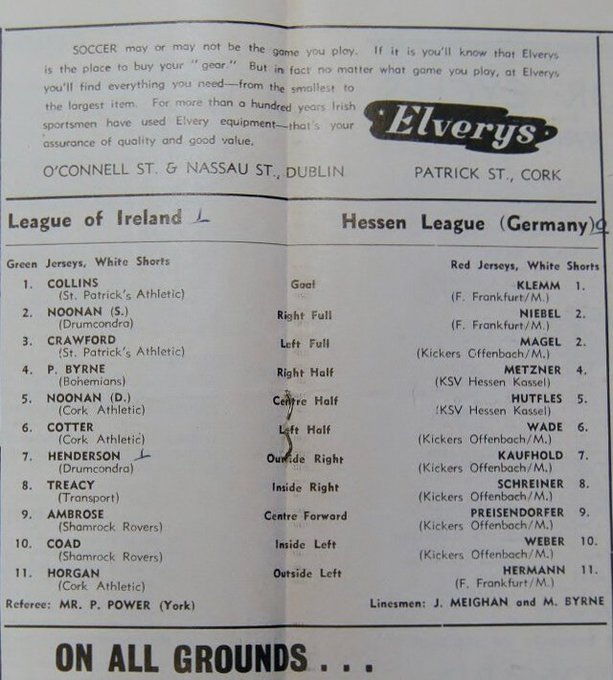

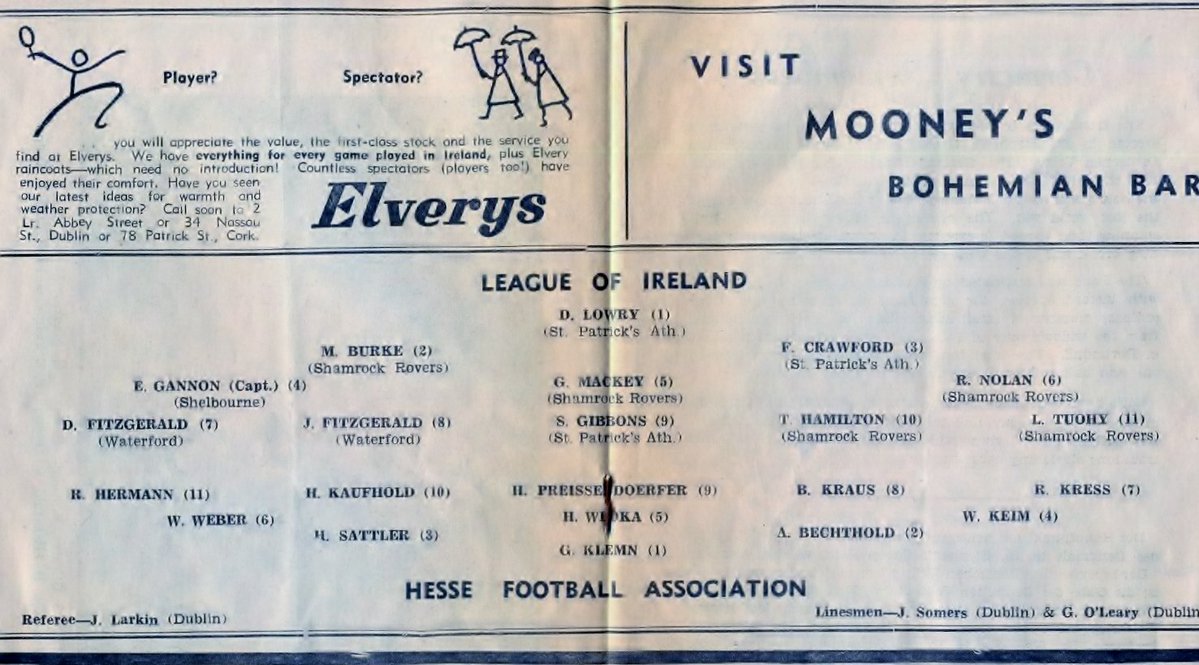

More positively it put the League of Ireland on an equal footing with the Irish, Scottish and English leagues, no more could the best talent in the league be snapped up for absolutely nothing (though plenty of British clubs still try), transfer fees had to be paid and over the intervening decades this proved crucial in keeping many League of Ireland clubs afloat. Another benefit of the Glasgow conference was that the Scottish and English leagues agreed to start playing inter-league games against the League of Ireland. Previously these games had mostly been restricted to matches against the Irish or Welsh leagues, but now the best the English and Scottish Leagues had to offer would begin coming to Dublin while the League of Ireland selections would journey to Celtic Park, Goodison, Maine Road and Ibrox among others. These games were highly prestigious and importantly the large crowds they attracted to Dalymount were significant revenue generators.

For so long League of Ireland fans have become used to a certain condescening attitude towards their clubs from their British counterparts, especially in relation to transfer fees for players, many of whom have gone on to have excellent careers. Everton fans still sing about getting Seamus Coleman from Sligo Rovers for “60 grand” as just one example. With this in mind it is interesting to look back at post-war stories in the British media where sports columnnists and football club officials fretted about the spending power of rogue Irish clubs enticing away the best of British talent.