Dalymount before Bohemians

1847 – the height of the Great Famine and in Dublin the Ordnance Survey were engaged in the first major survey of Dublin since John Roque produced his famous map in 1756. On the plan one can clearly see the North Circular Road intersecting Phibsborough Road as it headed towards St. Peter’s Church. On the right a short row of five houses bearing the name Daly Mount. But who precisely was the eponymous Daly of the mount? This brings us to Peter Daly, a prosperous businessman involved in shipping and also Chairman of the Orange Lodges of Dublin. He owned a tavern in Werburgh Street that bore his name and was described as a ‘Temple of Orangeism’. Indeed in 1823 a group of Orangemen had met in his tavern before staging a riot in a nearby theatre intended to intimidate Richard Wellesley, the Lord Lieutenant including chants of “No Popery!”, due to his support for Catholic emancipation.

A 1834 report in the Dublin Evening Packet recounts the funeral of Peter Daly, when his body was borne from his home at Dalymount through the city down Sackville Street as far as Werburgh Street Church to his family crypt, with many businesses closing along the route for the funeral procession. His eldest son Samuel Allen Daly, also living in Daly Mount became a church warden in Grangegorman the year after and in 1836 became a barrister. By 1844 he had been elected to the Poor Law Union board of guardians for the Glasnevin area. It it reasonable to surmise that it was this family who first developed the houses along the north circular road that appear in the survey map of 1847.

Around this time the area now occupied by Dalymount Park was depicted as being grassland or farmland while the area now occupied by the tram sheds between the stadium and shopping centre looks like it may have been a garden or orchard. Further research shows that the lands occupied under long term leases by the Daly family and which included areas now occupied by the shopping centre, were ultimately the property of the Monck family and this likely included Dalymount. The Monck family were members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and their name is still visible in the area in street names like Monck Place just off the Phibsborough Road.

The Monck family came to own their Phibsborough estates through marriage, George Monck, was created 1st Duke of Albemarle in 1660 by Charles II arising from his services to the monarchy in bringing about the Restoration of the English monarchy. The Irish connection of the Monck family dates from 1627 when Charles Monck was appointed Joint Surveyor General of Customs in Ireland. He purchased an estate in county Westmeath and also represented Coleraine in the English parliament. Their son, Henry Monck, married Sarah, the daughter and heiress of Sir Thomas Stanley of Grangegorman, whose sizeable estates (including Dalymount and the surrounding streets) became vested in the second son of the marriage, Charles Monck. Overall, at the peak of their influence the Monck estate owned over 14,000 acres across five counties.

Samuel Allen Daly began lease arrangements with Henry Monck on these lands starting in 1835, however by the 1850s it seems that Samuel’s financial situation had worsened significantly and by 1855 his various leases around the Dalymount site and surrounding area were up for sale.

But let us talk briefly of Bohemians…

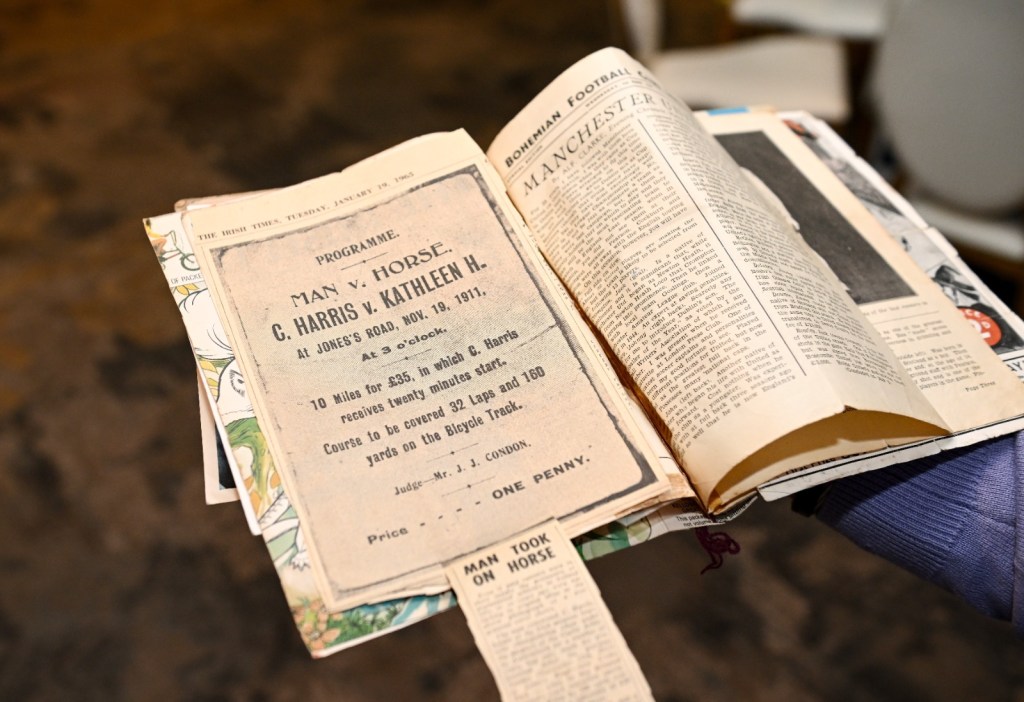

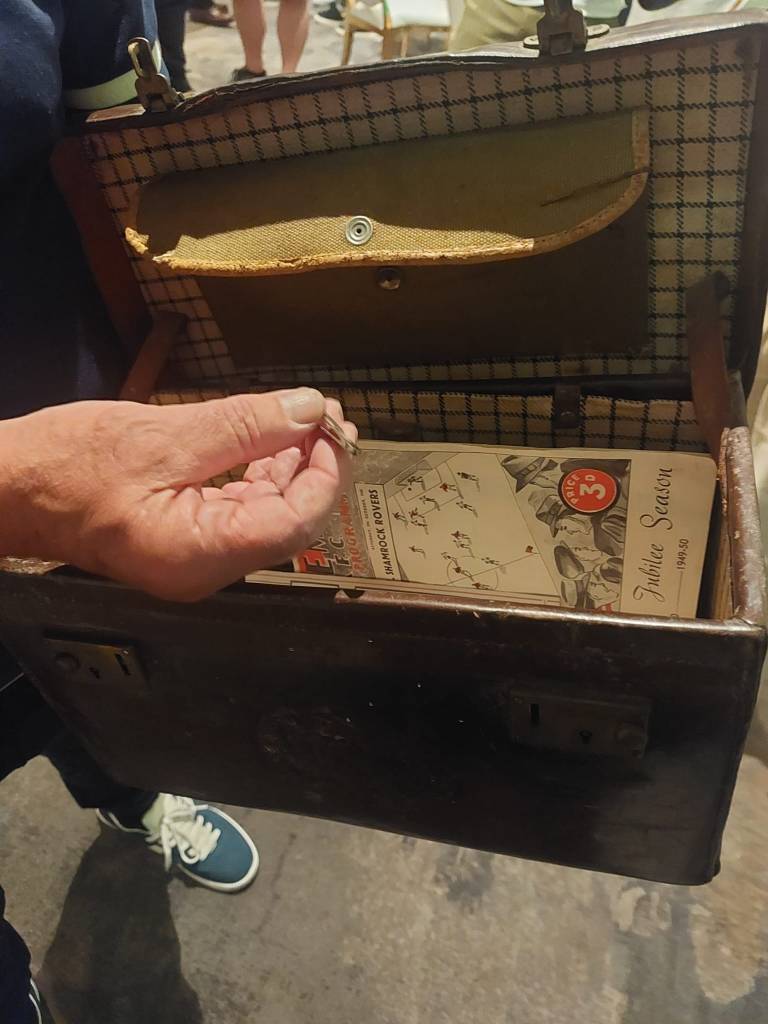

The Bohemian Football Club, founded in the North Circular Road gate-lodge of the Phoenix Park in 1890 had endured a peripatetic existence in their first decade, playing in the likes of the Phoenix Park, then in the Jones’s Road sports grounds, now site of Croke Park from 1893-96, and then in an area known as Whitehall, close to Glasnevin cemetery and the Finglas Road as we know it today. It was this wandering existance that some have suggested gave Bohemians their nickname of the “Gypsies”.

That was all to change however in 1901, when according to his own account, the club’s Honorary Treasurer William Sanderson, when visiting a friend in Connaught Street, looked over a back wall at what was known at the time as “Pisser Dignam’s field”, and got the idea that it might be a suitable home for the Bohemian Football Club. Though who Pisser Dignam was and how he got such a moniker remains unclear!

As for Sanderson, he was a tailor born in Belfast but a long-time resident in Dublin. He had been involved with the early YMCA and Tritonville football teams before getting involved with Bohemians in the 1890s eventually becaming Treasurer in 1900. Sanderson was clearly a man with a head for finances and could spot the opportunity that a well placed sporting ground could offer. He recalled that a cup tie against Linfield in 1900 had generated a Dublin record of £39 in gate money at the old Whitehall ground. Imagine what a better situated ground, adjacent to a busy tram line could generate!

The land itself was used for small scale allotments growing vegetables and fruit trees, horse grazing and also as something of a rubbish tip. The early Dalymount Park groundsman, Dinny Quinn would keep shotguns in the ground which he used to get rid of hares and rabbits that might be found digging up the pitch. On the plus side, it was a central location, only a twenty minute walk from the centre of the city, situated in a rapidly developing suburb and adjacent to a tram line which added to ease of access for both players and spectators. But to take a lease on the ground the club would have to contact the property owners.

This brings us from the Monck estates to the Taylor family. In one version of the story, by the late football historian Tony Reid, it was Sanderson and the Bohemian FC committee negotiating with the Reverend Henry Taylor who was acting on behalf of the Monck estate over the leasehold of what would become Dalymount Park. However, some subsequent research would suggest that Taylor was acting not on behalf of the Monck estate but on behalf of his own familial interests.

Henry Taylor was the son of Thomas and Sophia Taylor and was also the chaplain to the the Female Orphan House, more commonly known as Kirwan House which is one of Ireland’s oldest charities, founded in the 1790 at 42 Prussia Street to look after orphaned girls and to train them to be domestic servants and in the manufacture of clothing, and built on lands of the Monck estate.

The girls of the home received the following training and treatment at the “Orphan House, near Dublin, for the support of destitute female children, it is proposed that they shall be received from the age of five to ten years; that they shall be lodged, clothed and taught reading, writing, and common accounts; carefully instructed in the Christian Religion; and habituated to cleanliness and industry, in proportion to their age and strength; to spin, knit and when able, to make their own clothes. They are to take in plain work as the Charity advances; the profits arising from which are to be applied towards the support of the House”

It is named Kirwan House after Dean Kirwan who used to preach on behalf of the charity and raise funds for it annually in St. Peter’s Church in Aungier Street.

A description of the average day for one of the orphaned children in the 19th Century is detailed below on the History Eye website – “The orphans rose at 6 in the morning and retired to bed at 10pm. Their day was divided into three segments. Eight hours for work and instruction, eight hours for play and worship, eight hours for sleep. There was meat provided three times a week and dinner was served at 2pm. Each orphan’s upkeep was set at 3 pence a week or 10 shillings a year. Porter was also provided in the children’s diet for health reasons.”

Returning to Rev. Henry Taylor and the connection with Bohemian FC. Taylor would combine his role as Chaplain at Kirwan House with a position on as a Vice President of Bohemians (there were several club Vice Presidents, numbering between eight and fourteen at various stages) between 1901 and 1920. One suggestion proposed was that Taylor may also have represented the Monck estate in matters related to the lease of Dalymount Park and as such would have been their placeman on the board to make sure that they were happy with the use and development of Dalymount as a sporting venue. However, it seems that Henry’s father, Thomas had already purchased Dalymount Park long before William Sanderson had the bright idea to use it as a football ground.

As far back as September 1869 The Freeman’s Journal, in an article discussing the revision of boundaries in Dublin mentioned “Thomas Taylor, of Prussia Street, described as a 50l [pound] freeholder out of houses in Dalymount and Fassaugh Lane”. We know that Thomas Taylor was part of the same Grangegorman religious congregation as Viscount Monck and that in the early 1870s both men served it as Vestrymen. Taylor also lived on Prussia Street for much of his life, before eventually moving the short distance to Cumberland Place on the North Circular Road, right next to Kirwan House.

We can see how, given the congrational aspect and the close physical proximity that connections with the likes of the Monck family, the Daly family and others could have developed. We know that Thomas Taylor (who was born around 1805) was well established in the area, by 1862 he is mentioned in The Freeman’s Journal, along with his Prussia Street neighbour John Jameson of whiskey fame, as two property owners that Dublin Corporation were intending to buy lands from in order to develop the Cattle Market site.

In later life, when appearing on offical civic documents such on his daughter’s marriage certificate or even on his death certificate, his profession is listed simply as “Gentleman” showing that he had sources of income primarily from his various property holdings, though as far back as his son Henry’s birth in 1851 he is referred to as a “Retired Government officer”. It is likely that Thomas purchased the land when it was put up for sale by Samuel Allen Daly in the 1850s when he was experiencing financial difficulties. Thomas would pass away at the age of 84 in 1889, while his wife Sophia would follow him in 1895. Her son, Henry was by her bedside when she passed away.

It would them seem that Henry, rather than acting on behalf of the Monck estate was acting in his own family’s interest when an annual rent of £48 was agreed with Bohemians. William Sanderson would pay the first three months out of his own pocket. Whether a role as a club vice-president was offered to Taylor as part of this negotiation, or requested by him is unclear, however is was a position he served with Bohemians for almost twenty years, leaving in 1920 as he approached his seventieth birthday.

Throughout his busy life Henry Taylor had held many roles, he had been a student in Trinity College, though his time there would have been before the foundation of their Association Football Club in 1883, he was Chaplain not only in the Kirwan House orphanage but also at the Royal Hospital in Donnybrook (The Royal Hospital of the Incurables), was private chaplain to the Lord Lieutenant and from 1908 until 1932, was honorary Clerical Vicar to Christ Church Cathedral. In later life he went in retirement to live with his daughter Dr. Eleanor Taylor-Pengelly in Orpington, Kent where he passed away aged 85 in 1937.

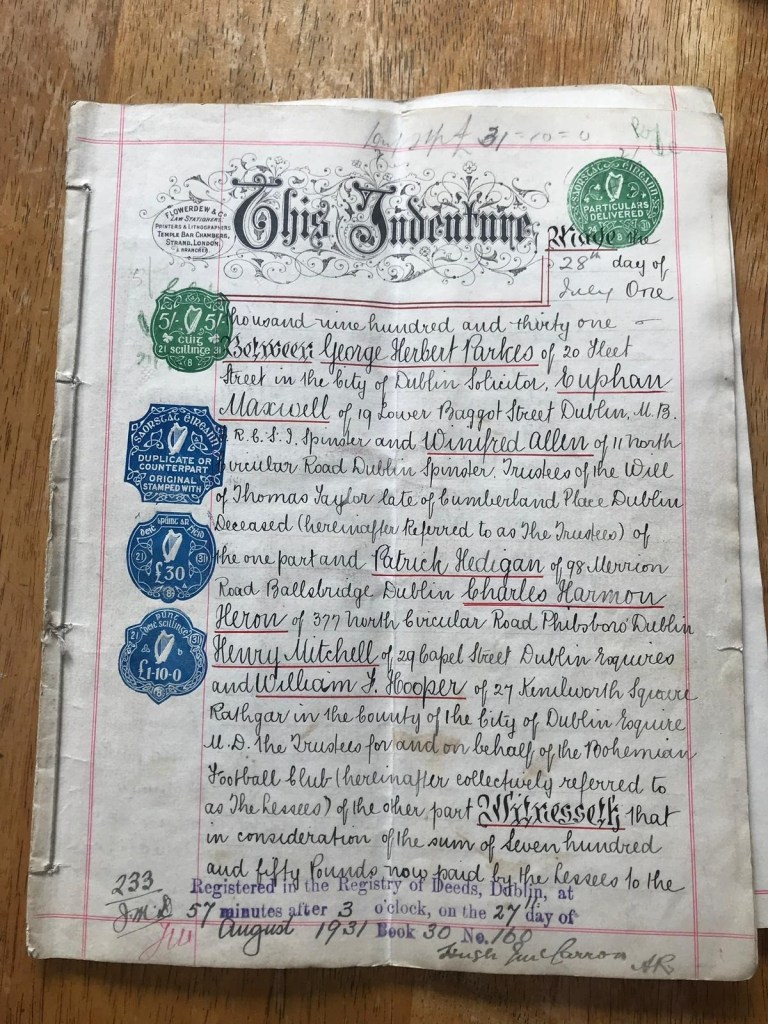

Henry Taylor would have been around eighty, and more than a decade removed from his role as one of the vice-presidents of Bohemians when the renewal of the lease was up for discussion again in 1931. By this stage Bohemians were making ambitious plans to further improve Dalymount and make it the best Association Football ground in the country, bringing in the famous stadium architect Archibald Leitch to develop the main stand and the Tramway end terracing in 1931. Dalymount was by this stage the unquestioned home of Irish football and the venue for Cup finals and international matches.

Negotiating this lease on behalf of Bohemians were Charles Heron, Henry Mitchell and Patrick Hedigan, all local businessmen and supporters of the club. Heron ran a butcher’s shop on the North Circular Road with family members running similar shops on Dorset Street, Mitchell ran a printing business on Capel Street (his family still operate on the street, from Mitchell’s Auto Shop) and counted Oscar Traynor as a former employee of his. Traynor had surreptitiously printed nationalist propaganda posters and newspapers during his time there. Finally, Patrick Hedigan, a Limerick man, was the owner of Hedigan’s – The Brian Boru public house since 1904, the pub is still in the ownership of the Hedigan family to this day and they continue to be a sponsor of the club.

Representing the Taylor estate wasn’t Henry however, the family trust’s solicitor was George Herbert Parkes, a maternal grandson of John West Elvery of Elvery Sports fame. George practiced from offices on Fleet Street in the city centre – incidentally a solicitor named Parkes, former player Warren Parkes, represented Bohemians against a winding up order in 2011, any relation? There were two other trustees were named, Dr. Euphan Maxwell and Winifred Allen. Maxwell was was an Irish ophthalmologist and the first woman ophthalmic surgeon in Ireland at the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, Dublin, however, she also lived for a time while a medical student with Henry Taylor and his sister Eleanor at the Kirwan House orphanage. Winifred Allen also lived on the North Circular Road and seems to have been a friend of Edith Parkes, sister of George Herbert Parkes. It seems that it was they who negotiated the new lease on Dalymount where Bohemians remain to this day.