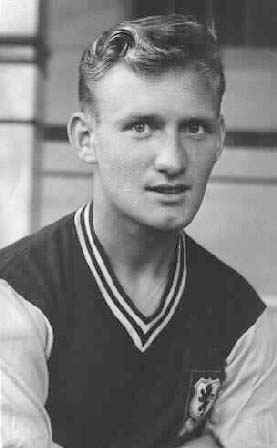

It all began in a two room house that no longer stands, on a street that no longer exists. In the summer of 1911, Joseph O’Reilly, a man who go on to be one of the greatest Irish footballers of his era was born at number 4, Willet’s Place. And, like the street where he was born, O’Reilly tends to be forgotten by history.

While Willet’s Place was just one of the many lanes and courts that snaked through Dublin’s impoverished north inner city, a place that many perhaps willingly forgot, Joe is someone who should be more familiar, especially to Irish football supporters. He was the first Irish player to win twenty international caps, a total that would have been significantly higher had the outbreak of World War Two not intervened. O’Reilly’s appearance record wouldn’t be broken until Johnny Carey won his 21st cap in 1949.

He was also a star of the domestic game, winning both a League and an FAI Cup with St. James’s Gate and represented the League of Ireland XI on many occasions. However, despite being a cultured half-back with a rocket of a shot, enjoying club success and scoring on his international debut in a win against the Netherlands, O’Reilly’s name provoked little response when typed into a search bar – a two line wikipedia entry being scant reward for an impressive career.

One reason that Joe O’Reilly is not a more prominent name in the history of Irish football could be down to the man himself. I spoke with Joe’s son Bob about his father and he stressed how little his father courted the limelight, describing him as a quiet and very humble man. Indeed the few articles and interviews that one can find on Joe O’Reilly see him focus praise and attention on his erstwhile teammates and rivals rather than on himself.

Ordnance survey map showing Willet’s Place (top centre right) c.1913 the Gloucester Diamond is shown bottom left.

Off the Diamond

To redress the balance I’ve tried to piece together a descriptive timeline of Joe’s life and career. In doing so let’s return to that two bedroom house in Willet’s Place, a back lane off what we know today as Sean McDermott Street. On May 27th 1911 a son is born to Michael and Mary O’Reilly, they christen him Joseph. This is an area that will become synonymous with Dublin football and footballers, Graham Burke, Jack Byrne and Wes Hoolahan are some of the more recent residents from the area who have worn the green, while the Gloucester Diamond became famous across the city for its 7-a-side matches that often featured the cream of Dublin’s footballing talent.

The Gloucester Diamond and its famous 7 a side concrete pitch – photo from local historian Terry Fagan

However, the O’Reilly family would not remain in the area long, they moved to another hotbed of Dublin football; Ringsend on the southern banks of the Liffey. Michael was a soldier in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers at the time of Joe’s birth and he was predominantly based out of Beggar’s Bush barracks, a short distance from the Ringsend/Irishtown area. The cramped house on Willet’s Place was the family home of mother Mary and shared with her parents Joseph and Mary-Anne Cooling. By 1916, when Joe’s younger brother Peter was born the family were living in one of the newly constructed houses in Stella Gardens, Ringsend. Named after Stella O’Neill, the daughter of local Nationalist Councillor Charles O’Neill these would have been an improvment on Willet’s Place and would have been highly sought after.

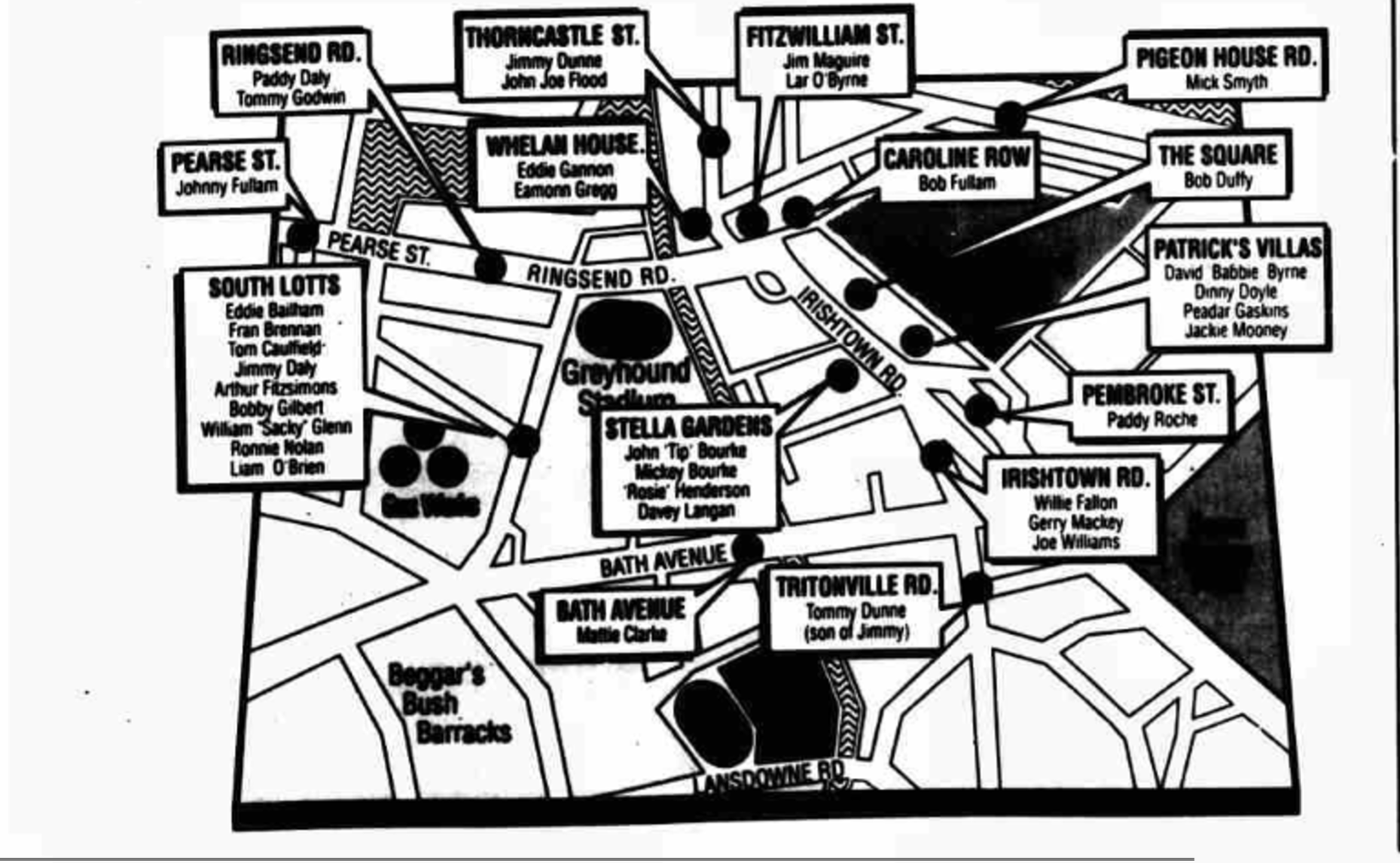

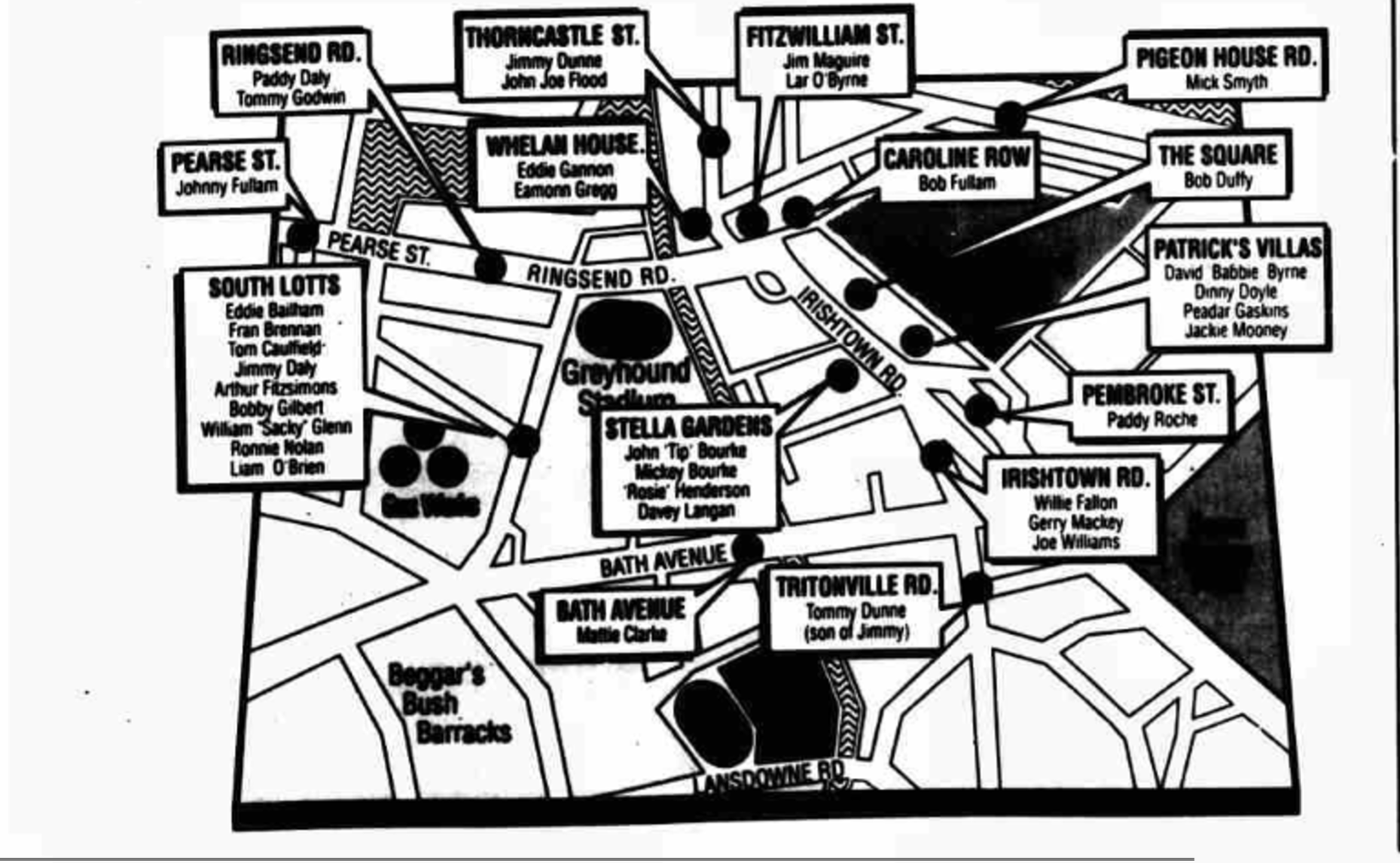

The family remained in the Ringsend area although the moved addresses at various times, being listed as living on the likes of South Lotts Road and on Gerald Street. Joe was the third child in a growing family that eventually would welcome seven children, four boys and three girls. Ringsend is of course an area synonymous with soccer, being the original home to both Shamrock Rovers and Shelbourne as well as one of Dublin’s oldest football clubs, Liffey Wanderers. The district has supplied the Irish national team with literally dozens of international players over the years and should count O’Reilly among its number, although he didn’t make the list when the Sunday Tribune set out to map all of Ringsend’s footballers back in 1994 (see below).

Sunday Tribune 1994 map of Ringsend’s footballers

The Ringsend Cycle

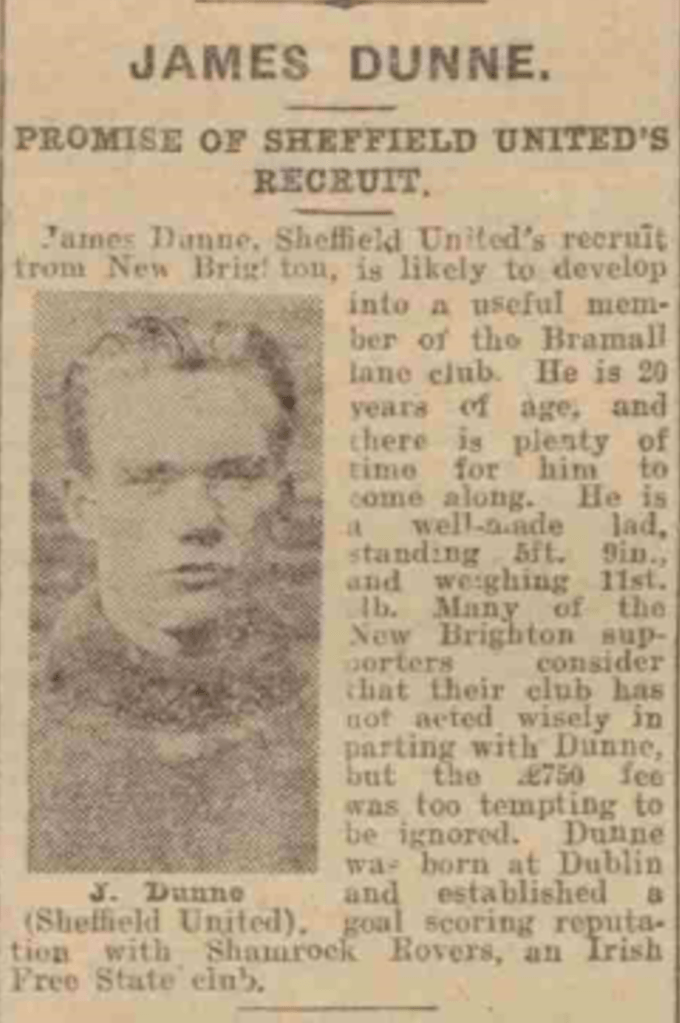

While born on the northside of the Liffey, and later to spend much of his life living in the then rural village of Saggart, south county Dublin it would be Ringsend that would provide formative influences on young Joe O’Reilly. Ringsend was home to Jimmy Dunne, who O’Reilly played with on numerous occasions for the national team, a man that he would continue to tell tales about years after he had hung up his boots. Ringsend was also home to Bob Fullam, one of the bona fide stars of Irish football in the 1920s, when terraces used to echo to the chants of “Give it to Bob”, in the hope that his rocket like left foot would create something spectacular. We’ll come on to Fullam later in our story but let’s begin with Dunne.

Jimmy Dunne was born in 1905, six years senior to Joe O’Reilly and packed a lot into those early years. While still a teenager he was interned by the Free State forces in the “Tintown” camp in the Curragh due to his involvement with the anti-treaty IRA, his older brother Christopher was also involved. By that stage Dunne was already something of a footballing prodigy and fellow footballer, and internee Joe Stynes remembered playing matches with Dunne in the cramped confines of the camp. According to O’Reilly’s son Bob, the Republican exploits of Jimmy Dunne extended back even further. During the War of Independence he remembered his father saying that Jimmy Dunne (then no more than 15 or 16) was a delivery boy for a local baker, and would use this job as a way to bring IRA messages across the city on his bicycle, hidden inside a loaf of bread.

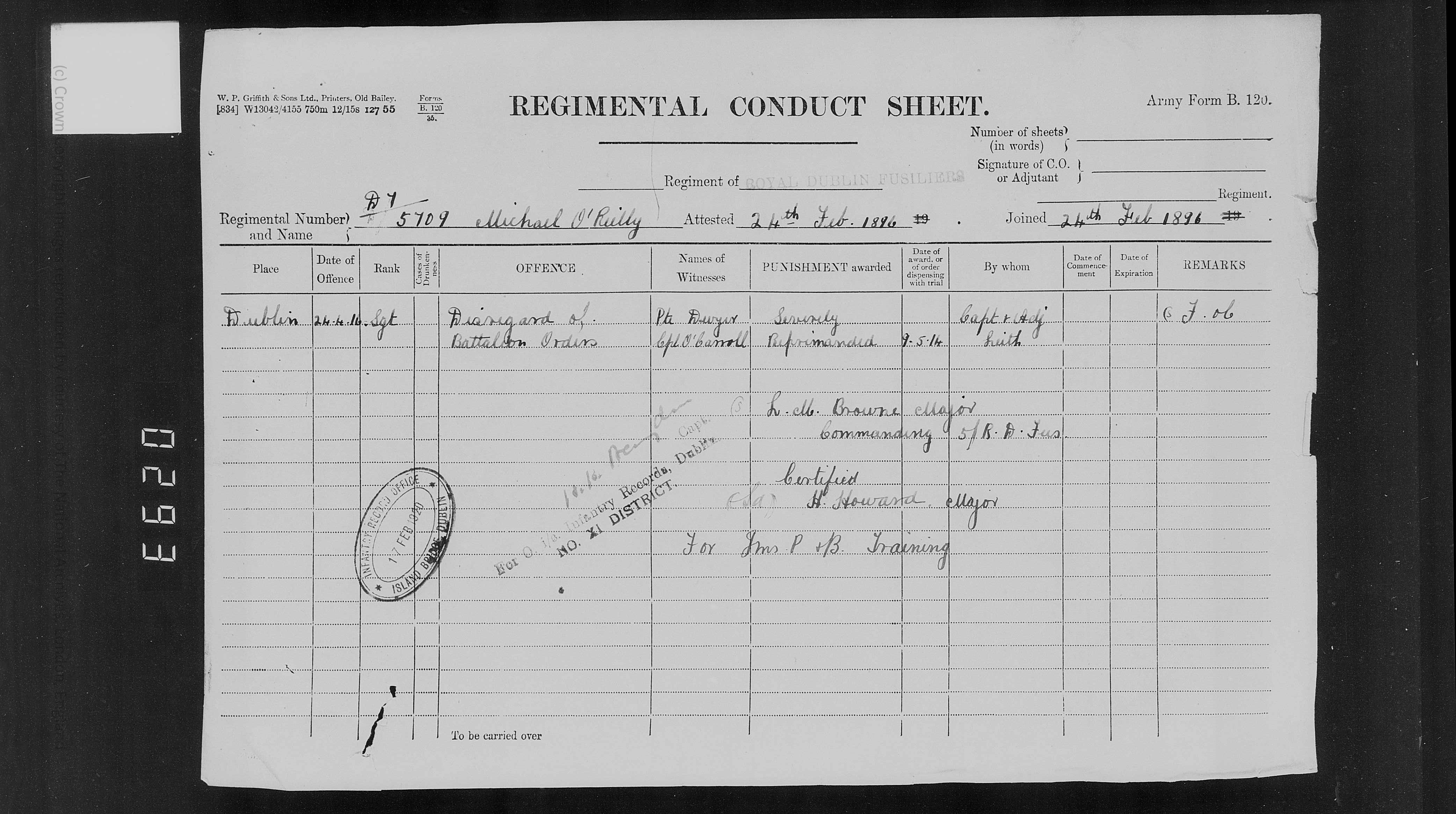

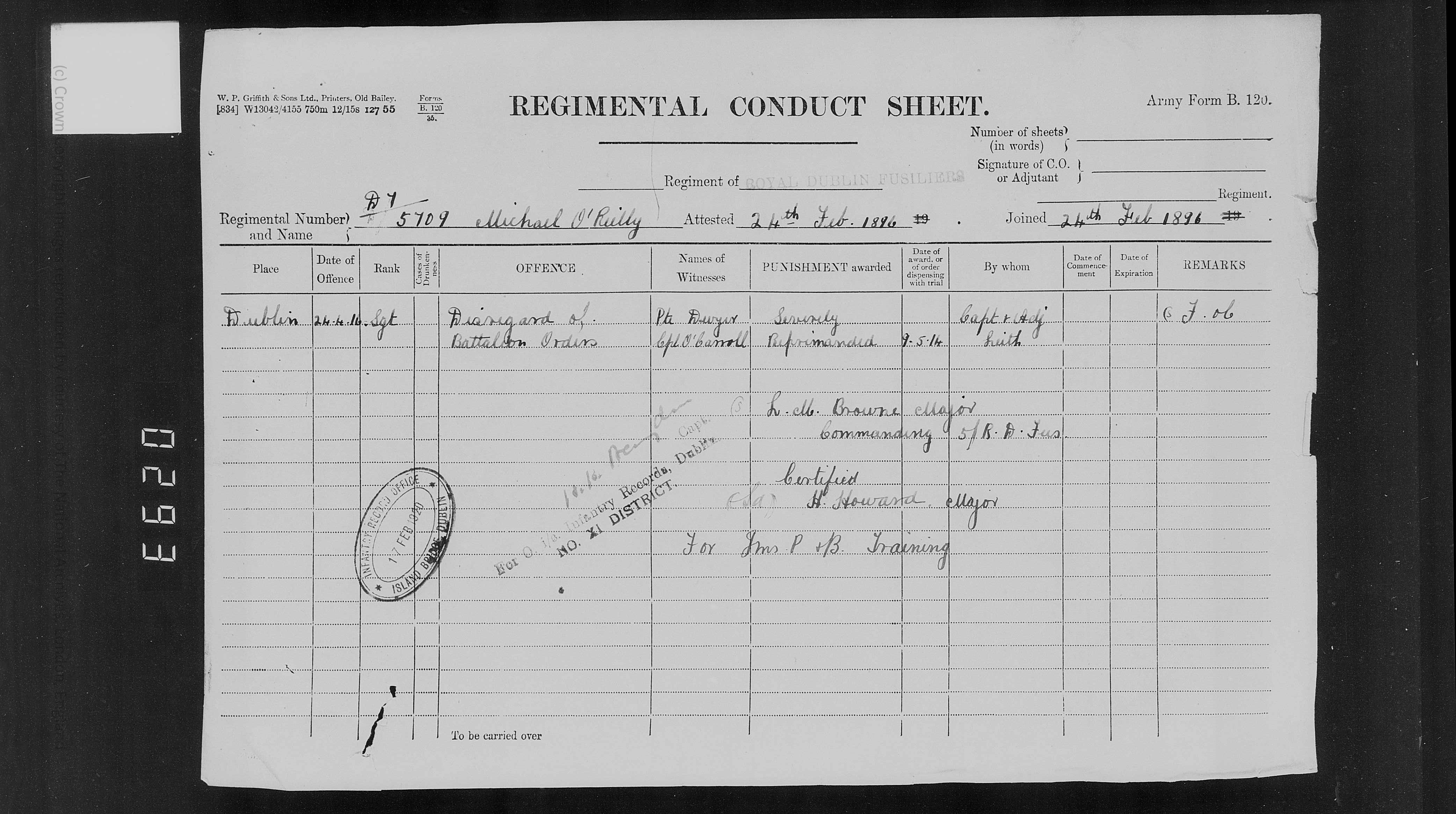

An additional layer is added to this when we turn to the life and career of Joe’s father Michael. As mentioned above Michael O’Reilly was a soldier with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. More than that he was a career soldier, having joined aged 18 and risen to the rank of Sergeant-Major and becoming and physical education instructor for the troops. He was a veteran of the Second Boer War and had an unblemished service record. Well – unblemished apart from one incident which caused him to be “severely reprimanded”. This reprimand related to a “disregard of battalion orders” when his battalion was based in Beggar’s Bush barracks in Dublin on the 24th of April, 1916. The day the Easter Rising began.

Reprimand issued to Michael O’Reilly on the outbreak of the Easter Rising

The specifics of this incident remain unclear but it worth noting that Michael O’Reilly was not a callow recruit, he was a 29 year old Sergeant with over ten years service and battle experience. According to family history Michael gradually became disillusioned with life in the Army and even began training IRA volunteers during the War of Independence after leaving the British Army in early 1920. We do know that he would go on to join the newly created Free State army and would be based in the Curragh camp during the War of Independence, perhaps he even watched his son’s future teammate Jimmy Dunne play a match in the Tintown prisoner camp?

Debuts and defeats

Joe O’Reilly would follow his father into the Army as a young man and was a member of the Army No. 1 band as a clarinet player. While in the army he also lined out for an unofficial Army football team, Bush Rangers (the Association game wasn’t recognised as an official army sport at the time) and it was clear that football was his first love. Aged just 18, Joe O’Reilly made his debut in the League of Ireland, helping Brideville to a win over Dundalk in October 1929. Joe started at the inside right position and scored in the win over Dundalk. Of his debut the newspaper Sport recorded –

“O’Reilly the newcomer, lacks training but he was responsible for many clever touches and a fine goal. He should be persevered with.”

And persevere they did. By the end of that seasons the teenage O’Reilly was a regular for Brideville as they finished fifth in the League of Ireland and was lining out in a Cup final against Shamrock Rovers who were embarking on a famous Cup dynasty. O’Reilly remembered being somewhat overawed by the occasion. He was not yet 19 and here he was starting in front of almost 20,000 in Dalymount Park, facing off against Irish internationals. He recalled years later that he must have looked somewhat of a nervous wreck as Rovers’ star Bob Fullam, a fellow Ringsend man, had a quiet word saying “I know you’re nervous, just do your best”. A small gesture but one which stuck with Joe.

The match didn’t go so well for Brideville though, ending in dramatic and controversial circumstances. With the game entering the 90th minute and the score level at 0-0 it looked like a lucrative replay might be on the cards. Rovers had a late attack and a hopefully ball was lofted into the box. David “Babby” Byrne, the Rovers striker got in between Brideville’s Charlie Reid and goalkeeper Charlie O’Callaghan and leaping with all of his 5’5″ frame guided the ball into the goal with an outstretched arm. 56 years before the dimunitive Diego Maradona did it, the FAI Cup had its own Hand of God moment.

The game’s colourful, English referee Captain Albert Prince-Cox saw no infraction and blew for the final whistle shortly afterwards. Joe had been denied the Cup in his debut season in cruel circumstances. By the end of that season Joe had moved further back on the pitch and instead of playing outside right he had moved into the half back line and his favoured role.

Despite the disappointment of losing the 1930 final further success on the pitch was not far off. In May 1932, just weeks before his 21st birthday Joe O’Reilly made his debut in Amsterdam against the Netherlands. Things got even better when just twenty minutes in O’Reilly scored the game’s opening goal with a rasping, curling shot from the edge of the box, in the second half Paddy Moore, the man who had replaced Bob Fullam as the talismanic figure at Shamrock Rovers scored a second to give Ireland a comfortable 2-0 victory in front of a crowd estimated at 30,000.

That first game for Ireland was an important one in Joe’s career as directly afterwards he, Paddy Moore and Shamrock Rovers’ winger Jimmy Daly, who had also featured against the Netherlands were signed for Aberdeen manager Paddy Travers for the combined fee of just under £1,000. The British transfer record at the time was £10,900 paid by Arsenal for Bolton Wanderers David Jack back in 1928, so to get three internationals for under a grand can count as a canny bit of business by the former Celtic player Travers. Joe became a full-time pro and was paid the princely sum of £6 a week for his efforts.

To the Granite City and back to the Gate

Things started well in the granite city for Joe, he was a first team regular for much of the season, alongside his international teammate Moore. While Jimmy Daly made a mere four appearances before returning to Shamrock Rovers, Joe would make 26 appearances in all competitions that first season, while Moore started off spectacularly, scoring 27 goals in 29 league games (including a double hat-trick against Falkirk) to help Aberdeen to 6th place in the League in the 1932-33 season.

However, the following season would be less successful for both men, while Moore still scored a respectable 18 goals in 32 appearances his strike rate had decreased and he eventually ended up going AWOL after returning to Ireland for a match against Hungary in December 1934, blaming injury and a miscommunication with Aberdeen. It seems that Moore’s problematic relationship with alcohol was impacting his performances, to the point that manager Paddy Travers had effectively chaperoned him back to Dublin for an international match against Belgium. Whatever Travers did seemed to work as Paddy Moore would score all four goals in a 4-4 draw in that game.

Joe’s issues were more prosaic, he felt alone and deeply homesick in Aberdeen which affected his form, he also faced stiff competition for a starting berth from club captain Bob Fraser who often played in the same position at right-half. While he would technically remain on the Aberdeen books by the beginning of 1935 Joe O’Reilly had returned to Dublin and Brideville.

After a year with Brideville he relocated the short distance to the Iveagh Grounds to sign for St. James’s Gate and it would be with the Gate that Joe would enjoy his greatest success domestically. While his first season with the Guinness team was not hugely successful the 1936-37 showed significant promise. For one thing the side featured a versatile teenager by the name of Johnny Carey who would be spotted by Manchester United and go on to captain them to League and FA Cup success during his 17-year stint with the club. While Joe and Johnny would only spend a few months together in the Gate first team they would don the green of Ireland together on many occasions.

The season would also bring around another FAI Cup final for Joe O’Reilly, more mature now, with international experience under his belt, surely this would be different to that teenage cup final defeat against a heavily fancied Rovers side? Alas for Joe this wasn’t to be the case, it was Waterford who triumphed in the final 2-1, bringing the cup to the banks of the Suir for the first time thanks to goals from makeshift centre-forward Eugene Noonan (more accustomed to playing at right back) and Tim O’Keeffe, with the Gate’s Billy Merry scoring a consolation goal late on.

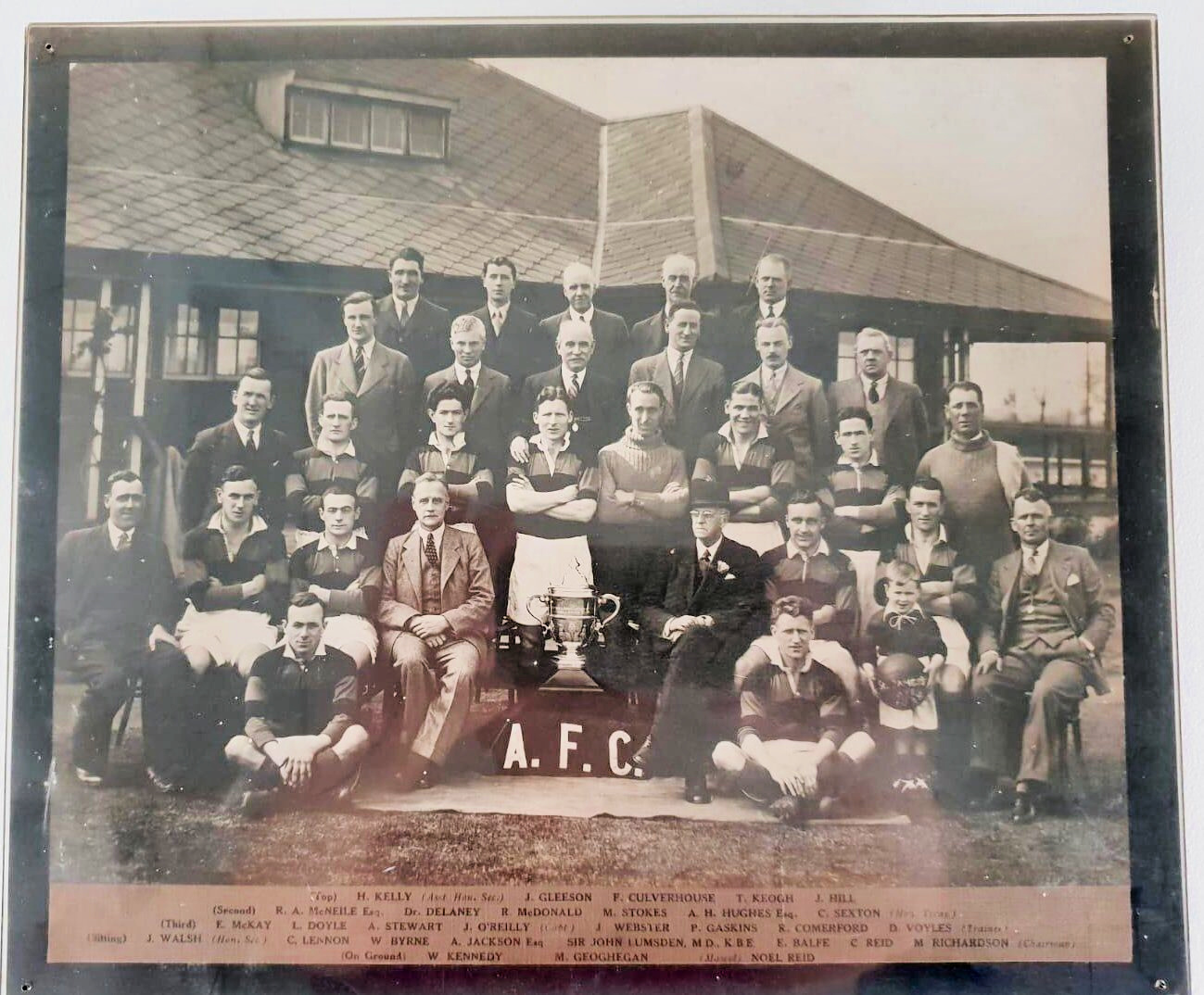

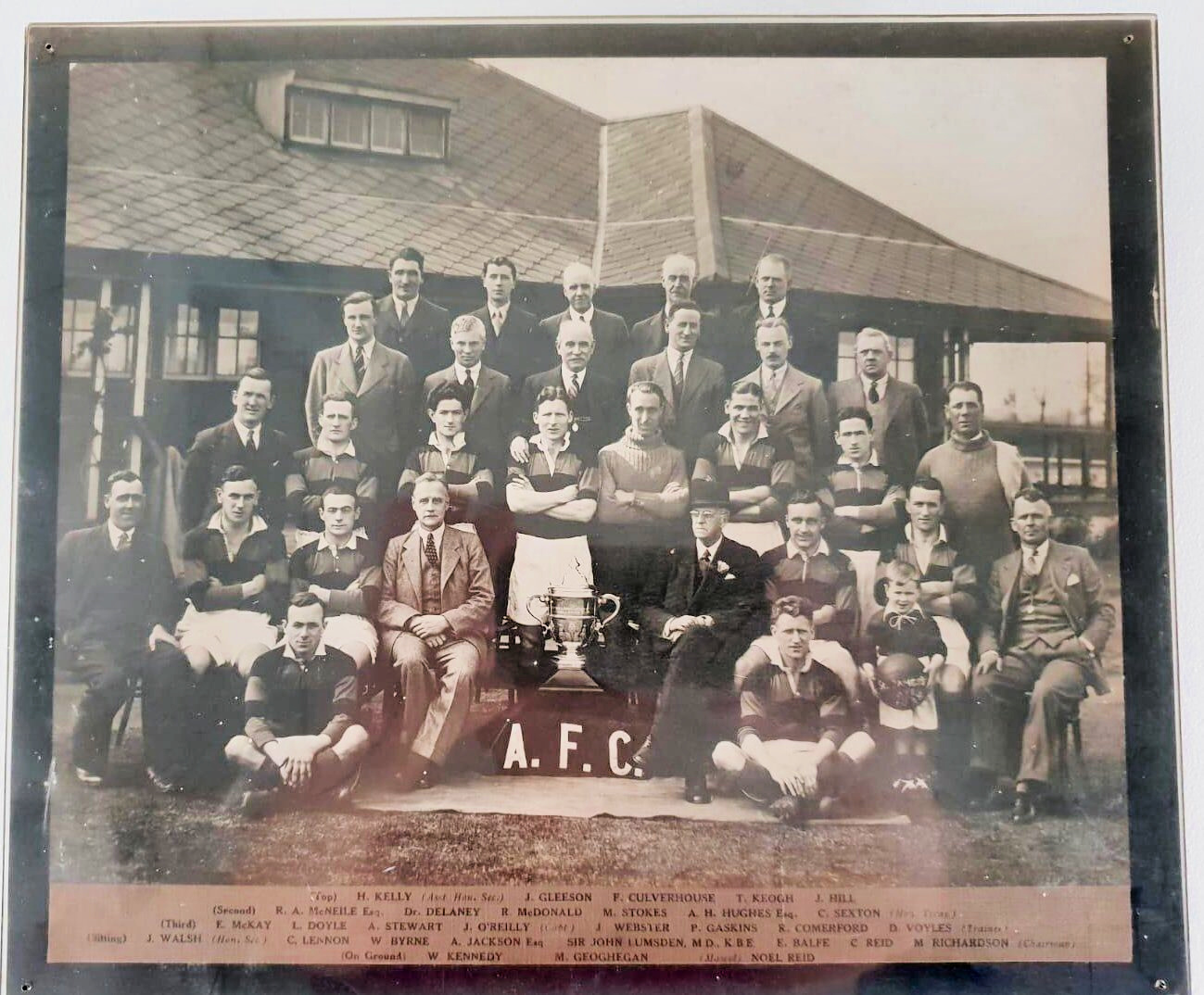

Two lost cup finals by the age of 25 – perhaps Joe thought he was cursed never to lift the trophy? But a year is a long time in football and 12 months later St. James’s Gate were back in the final again, and this time they would emerge triumphant, defeating Dundalk 2-1. Goals from Dickie Comerford and a second half peno from Irish international Peadar Gaskins sealing the win. Incidentally the consolation goal for Dundalk was scored by Alf Rigby, who had been a part of the St. James’s Gate side who lost the cup a year earlier, being on two different losing cup final teams, two years in a row is not a distinction that any player would enjoy.

That cup win in 1938 would mark itself out as an emerging high point in Joe’s career, not only had he won the cup, he had been the victorious captain, leading the Gate to their first win in 16 years. “A marvellous day and one I still treasure” recalled Joe in an Irish Independent interview decades later.

Joe standing behind the cup he had lifted in 1938 as team captain. (Credit Ger Sexton)

At international level Joe’s career was entering its prime. When he had made his debut in 1932 international opposition was difficult for the Irish team to find, near neighbours in Britain were refusing to play the national team in friendly matches for example. 1934 saw the first qualifying matches for the World Cup, Ireland were drawn in a group with the Netherlands and Belgium with Joe playing in both games.

The Belgium match entered the annals of Irish football history as one of the all time great international matches held in Dublin (and would perhaps set a national precedent for celebrating draws!) when Ireland drew 4-4. with Joe’s clubmate Paddy Moore scoring all four goals. The game against the Netherlands would be a disappointment however, despite taking the lead a late onslaught by the Dutch saw them run out 5-2 victors.

For the remaining five years Joe was pretty much an ever-present in the Irish team, playing a then record 17 consecutive international matches. He would score a second international goal in a 3-3 draw with Hungary in Budapest. Jimmy Dunne, also in record breaking form grabbed the other two.

A commemorative medal awarded to Joe after playing against Hungary in Budapest.

Joe also featured in both 1938 World Cup qualifying matches (home and away against Norway) however after a 3-2 defeat in Oslo a 3-3 draw in Dalymount wasn’t enough to get the side to France for the third installment of the tournament. Ultimately Joe’s international record read – played 20, won 8, lost 5, drew 7. This included some stand out victories over the likes of France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany.

The Germans

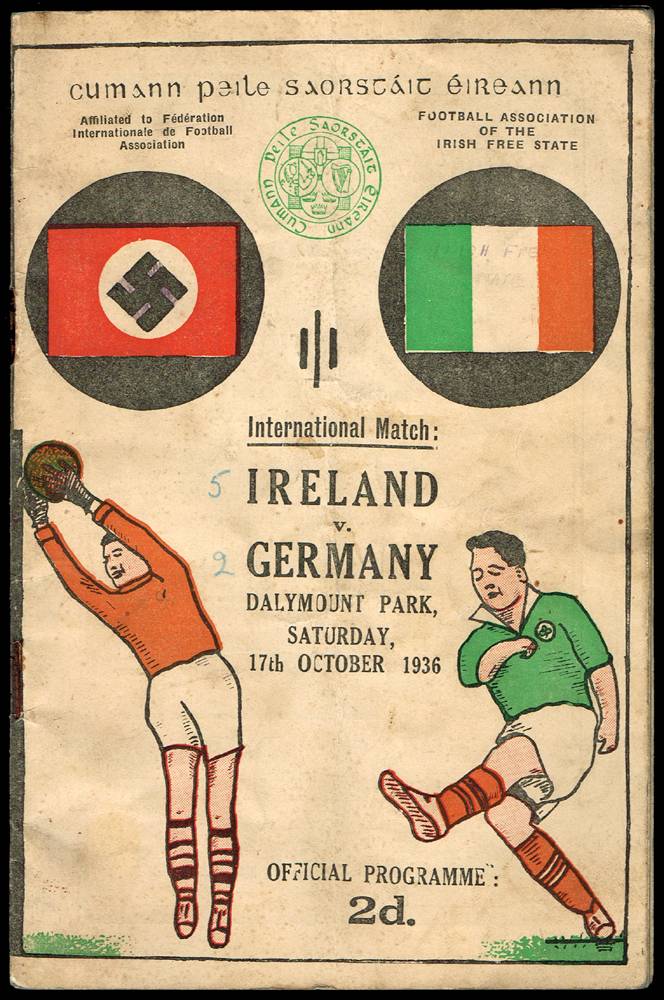

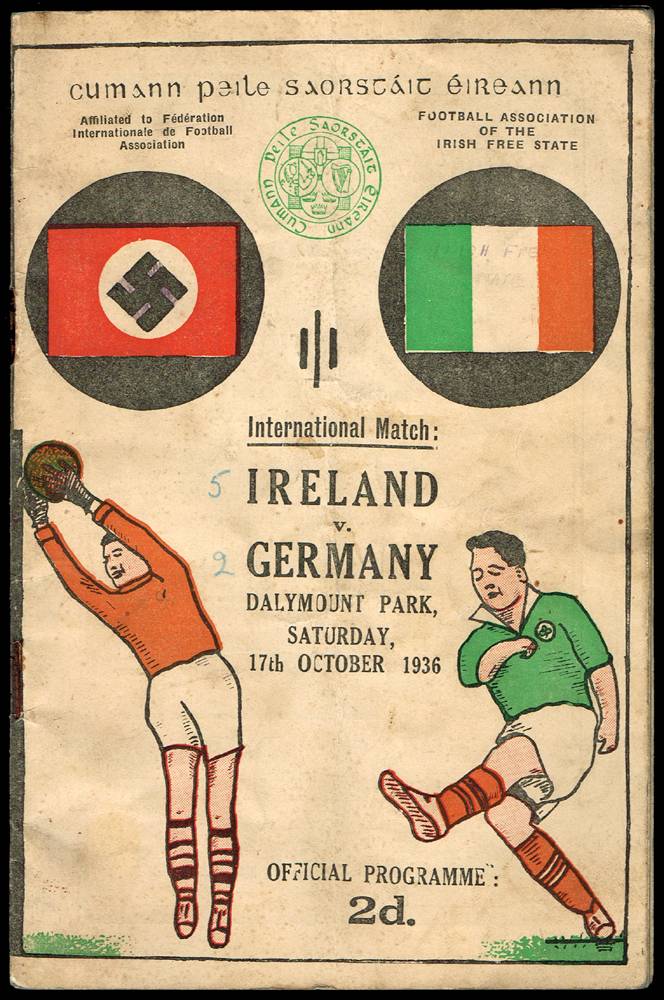

Two matches against Germany formed some of the clearest memories of Joe’s football career, which he discussed with both the Sunday World and Irish Independent many years later. The first of these matches took place in 1936 in Dalymount.

Infamous match programme from the 1936 game against Germany as presented for sale at Whyte’s auctioneers.

It was in this game that the German team, and over 400 German dignitaries gave the Nazi salute at Dalymount Park. Given the lens of history it is understandable that these events have tended to overshadow the team performance but it was something that shouldn’t be overlooked. The Irish side ran out 5-2 winners with Oldham’s Tom Davis scoring a brace on his debut, and Paddy Moore, slower, less mobile, but still perhaps the most skillful player on the pitch pulling the strings from the unusual position for him of inside left and creating three of the five goals.

This was something of an Indian Summer in Moore’s career (a strange thing to say about a man aged just 26), he was back at Rovers and was instrumental in helping the Hoops win the 1936 FAI Cup and he lit up Dalymount that day against Germany. It was his second last cap for Ireland, followed by an unispiring display in a 3-2 defeat to Hungary two months later. Injury and Moore’s well- documented problems with alcohol had, not for the last time, derailed a hugely promising football career. He finished his Ireland career with nine caps and seven goals.

Joe O’Reilly knew Paddy Moore well, from their time in Aberdeen, their outings together on the Irish national team and from facing him in the League of Ireland. When interviewed in the 1980s by journalist Seán Ryan, he said this of Moore;

He was a wonderful footballer, a wonderful personality. The George Best of his time… He was a very cute player. If, in a match, things weren’t going his way, he could produce the snap of genius to turn the match around – and he was always in the right spot. I had a good understanding with him.

Of that 5-2 win O’Reilly remembered it as the highlight of his playing career, telling Robert Reid in the Sunday World many year later;

The highlight for me was our 5-2 win against the Germans in 1936. Their ultra-nationalism acted as an incentive for us… what they weren’t going to do to us… and we beat them 5-2!

The second game against the Germans was even more controversial and took place three years later in May 1939, it would be the last international match played by the German national team before the outbreak of the Second World War. Similarly it would be the Irish team’s last international match until 1946. Of the eleven Irish players who took to the pitch in Bremen in 1939, only two, Johnny Carey and Kevin O’Flanagan would play for Ireland again.

The match was also a personal landmark for Joe O’Reilly as he became the first player to win 20 caps under the stewardship of the FAI. I’ve written previously on the details of that game in Bremen, the views of the FAI, and more widely about Ireland’s sporting relationship with Germany at this time. It was Joe’s recollections that however, provided one of the quotes that has endured, and it wasn’t even a direct quote from Joe, but rather his memories of Jimmy Dunne.

Dunne, who had never lost his socialist, Republican ideals, gave the Nazi salute under duress. As Joe recalled:

As we stood there with our right arm outstretched, Jimmy kept saying to me ‘Remember Aughrim. Remember 1916.’ By the time the anthem finished, I wasn’t quite sure who was more agitated the Germans or us.

As well as an interest in politics Dunne obviously seemed to have some interest in Irish history. O’Reilly recalls ahead of a game against Norway the usually laconic Dunne riled up his Irish teammates with references to Brian Boru’s victory over the Norse at the Battle of Clontarf. However, Dunne’s attitude in Germany stood in contrast with the official view of the FAI was recorded in the words of Association Secretary Joe Wickham. who said, “In Bremen our flags were flown though, of course, well outnumbered by the Swastika. We also, as a compliment, gave the German salute to their Anthem, standing to attention for our own. We were informed this would be much appreciated by their public which it undoubtedly was.” That the Irish athem was even played was in part down to Joe. On learning that the German band didn’t have the right sheet music Joe was able to write the notation to Amhrán na bhFiann from memory, thanks to his days in the Irish Army band.

Reflecting on his last cap more than 50 years later Joe felt the benefit of hindsight, appreciating things he perhaps didn’t as a sportsman in his 20s. He told Robert Reid;

But war was in the air. You could see it all around you, although you didn’t fully appreciate the extent of what was about to happen. How could anyone have known?

The anti-semetic feeling was already evident. But it was difficult to fathom what was really going on.

I remember the German soldiers. The shouts of “Heil Hitler” and the way we reciprocated their gesture. It was done in pure innocence. It just seemed like the thing to do at the time. I remember the young faces. I still remember them and wonder whatever happened to most of those young people, Germans, Jews, all the nationalities…

This match would be the last that Joseph O’Reilly played for his country, his international career ended, a week before his 28th birthday and three months before the Schleswig-Holstein battleship fired the first shots of World War Two.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Above are the panels on an international cap awarded by the FAI reprepsenting games that Joe O’Reilly played for Ireland in 1938 and 1939.

Epilogue

While Joe’s international career had come to a premature end his club career continued unabated. Unlike many European leagues the League of Ireland continued in as close to a normal capacity as was possible, during the years of the Second World War.

The 1939-40 season was to be one of great success for Joe as he captained St. James’s Gate to the league title. The men from the brewery finishing six points clear of nearest rivals Shamrock Rovers, while the Gate’s Paddy Bradshaw (who had scored in the 1-1 draw against Germany in Bremen) would end as the league’s top scorer with 29 goals.

Joe continued with the Gate until the 1943-44 season when the club disappointingly finished bottom of the league and failed to gain re-election, the club announcing that they were to revert to an amateur status thereafter. This wasn’t quite the end of Joe’s top flight career, as the club that replaced St. James’s Gate was his former side Brideville, returning to the League of Ireland after one of their periodic absences. Joe, now in his mid 30s signed on for one more season with the men from the Liberties before eventually hanging up his boots.

By this stage Joe had relocated to Saggart in south county Dublin and was working with Swiftbrook paper mills, a well established business who made official paper for the likes of the Irish Government, and according to historian Mervyn Ennis, James Connolly used the paper milled in Saggart for the publication of the Socialist Magazine, and when it came time to print it, the 1916 Proclamation. By this stage Joe had met and married his wife Helen and together they would eventually have six children; Geraldine, Helen, Maureen, Patricia, Bob and Brian.

Joe and Peter O’Reilly

Sport remained an interest throughout the family, from Joe’s father Michael, the physical education army man who later trained Kildare’s footballers for All-Ireland success in 1928, while his brother Peter who won an All-Ireland with Dublin in 1942. Even his son Bob made the Dublin GAA team league panel in the early 80s as well as playing soccer on the books of Shelbourne.

By all accounts a quite and humble man who preferred to amplify the achievements of others, Joe did gain some wider recognition later in life, being a recipient in 1991 of an Opel Hall of Fame award alongside Paddy Coad and Dundalk’s Joey Donnelly.

The Opel hall of fame award presented to Joe in 1991.

Joe passed away in October 1992 just a year after the receipt of this award. While he surprisingly remains little remembered in many Irish football circles he was one of the most talented and technically astute players for Ireland and an early international record breaker.

A special thank you to Bob O’Reilly for sharing memories of his father as well as many of the photos that feature in this article.

of Ireland’s greatest ever keepers and a founder of somewhat of an Irish goalkeeping dynasty. (Not the only one mind, hello to the Hendersons) Alan Kelly Sr. was a FAI Cup winner and a League champion with Drumcondra during their 1950’s heyday when he made his debut for the Republic of Ireland as they defeated World Champions Germany 3-0 in Dalymount Park. Before long a move to Preston North End beckoned and he spent 14 years as a player at Deepdale making a club record 513 appearances, including an impressive performance in the 1964 FA Cup final where the unfancied Preston were deafeated 3-2 by the West Ham of Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst. Such was his importance at Preston that in 2001 a redeveloped stand was named after him. Kelly would later manager Preston and would assist John Giles during his managerial reign as well as being caretaker manager for Ireland during a 2-0 win over Switzerland.

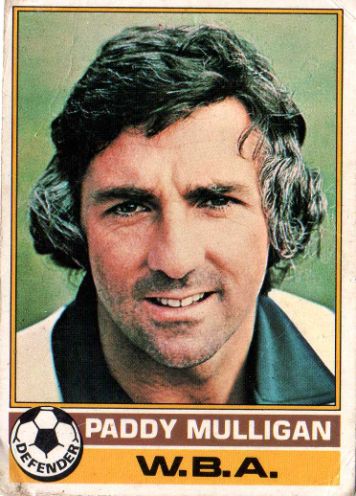

of Ireland’s greatest ever keepers and a founder of somewhat of an Irish goalkeeping dynasty. (Not the only one mind, hello to the Hendersons) Alan Kelly Sr. was a FAI Cup winner and a League champion with Drumcondra during their 1950’s heyday when he made his debut for the Republic of Ireland as they defeated World Champions Germany 3-0 in Dalymount Park. Before long a move to Preston North End beckoned and he spent 14 years as a player at Deepdale making a club record 513 appearances, including an impressive performance in the 1964 FA Cup final where the unfancied Preston were deafeated 3-2 by the West Ham of Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst. Such was his importance at Preston that in 2001 a redeveloped stand was named after him. Kelly would later manager Preston and would assist John Giles during his managerial reign as well as being caretaker manager for Ireland during a 2-0 win over Switzerland. might of Real Madrid 3-2 on aggregate in the Cup Winners Cup final before moving onto Crystal Palace and later West Bromwich Albion, managed at the time by his international team-mate Johnny Giles. While Paddy finished his career with a very respectable 50 caps he didn’t have the easiest start to his international career, he was a part-timer with Shamrock Rovers while also holding down a job with the Irish National Insurance Company when he was called up to the Irish squad in 1966, his employers weren’t too happy about his decision to travel with the squad to face Austria and Belgium and he was issued with an official warning by the company directors!

might of Real Madrid 3-2 on aggregate in the Cup Winners Cup final before moving onto Crystal Palace and later West Bromwich Albion, managed at the time by his international team-mate Johnny Giles. While Paddy finished his career with a very respectable 50 caps he didn’t have the easiest start to his international career, he was a part-timer with Shamrock Rovers while also holding down a job with the Irish National Insurance Company when he was called up to the Irish squad in 1966, his employers weren’t too happy about his decision to travel with the squad to face Austria and Belgium and he was issued with an official warning by the company directors!

With Ireland trailing 3-0, thanks in no small part to the prolific Sporting striker Fernando Peyroteo, the Irish keeper Ned Courtney is forced to go off injured. Courtney kept goal for Cork United and was an officer in the Irish Army, he had also won a Munster title in Gaelic Football with Cork. Brought on in his place was Con Martin, who at the time was in the Irish Air Corps and had also won a provincial GAA football title, with Dublin in 1941, he kept a clean sheet for the remainder of the game and started in goal in the next match, a 1-0 victory over Spain. Martin was a hugely versatile player, he lined out as a centre half for Drumcondra he played almost an entire season in goal later in his career for Aston Villa and also regularly played as a half back or at inside forward. He was a regular penalty taker for Ireland and it was Con Martin who opened the scoring in the ground-breaking 2-0 win over England at Goodison Park.

With Ireland trailing 3-0, thanks in no small part to the prolific Sporting striker Fernando Peyroteo, the Irish keeper Ned Courtney is forced to go off injured. Courtney kept goal for Cork United and was an officer in the Irish Army, he had also won a Munster title in Gaelic Football with Cork. Brought on in his place was Con Martin, who at the time was in the Irish Air Corps and had also won a provincial GAA football title, with Dublin in 1941, he kept a clean sheet for the remainder of the game and started in goal in the next match, a 1-0 victory over Spain. Martin was a hugely versatile player, he lined out as a centre half for Drumcondra he played almost an entire season in goal later in his career for Aston Villa and also regularly played as a half back or at inside forward. He was a regular penalty taker for Ireland and it was Con Martin who opened the scoring in the ground-breaking 2-0 win over England at Goodison Park.

Despite treading the well-worn path going from Home Farm schoolboy to England, joining Arsenal aged just 18 it was as one the classiest players in Rovers’ “Cup Kings” sides that he made his name. After only two league appearances for the Gunners, O’Neill, then aged 21 joined Rovers on their Summer 1961 tour of North American where they took part in the grandly titled Bill Cox International Soccer League against the likes of Dukla Prague, Red Star Belgrade and Monaco. O’Neill impressed grabbing six goals in seven games after which he was signed for £3,000. O’Neill would make over 300 appearances for Rovers, winning a league title as well as six consectutive FAI Cups, mostly playing on the right wing. His international career coincided with a downturn in the national team’s fortunes though there were highlights including the scoring of his only international goal against Turkey in a 2-1 victory.

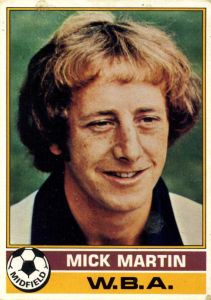

Despite treading the well-worn path going from Home Farm schoolboy to England, joining Arsenal aged just 18 it was as one the classiest players in Rovers’ “Cup Kings” sides that he made his name. After only two league appearances for the Gunners, O’Neill, then aged 21 joined Rovers on their Summer 1961 tour of North American where they took part in the grandly titled Bill Cox International Soccer League against the likes of Dukla Prague, Red Star Belgrade and Monaco. O’Neill impressed grabbing six goals in seven games after which he was signed for £3,000. O’Neill would make over 300 appearances for Rovers, winning a league title as well as six consectutive FAI Cups, mostly playing on the right wing. His international career coincided with a downturn in the national team’s fortunes though there were highlights including the scoring of his only international goal against Turkey in a 2-1 victory. team that day was comprised of League of Ireland players as the match had been scheduled just a day after a full English league fixture programme. He also made a number of appearances at the Brazil Independence Cup while still of Bohs player, scoring in a 3-2 win over Ecuador. Better was to come for Martin, he got to mark Pelé as part of a Bohs/Drumcondra select that took on Santos and shortly afterwards secured a move to Manchester United and later joining Johnny Giles at West Brom. In his club career he is probably most associated with Newcastle United, who he joined for £100,000 in 1978. He was hugely popular with the St. James’s Park faithful who dubbed him “Zico” and he got to play alongside the likes of Kevin Keegan and a young Chris Waddle during his time there.

team that day was comprised of League of Ireland players as the match had been scheduled just a day after a full English league fixture programme. He also made a number of appearances at the Brazil Independence Cup while still of Bohs player, scoring in a 3-2 win over Ecuador. Better was to come for Martin, he got to mark Pelé as part of a Bohs/Drumcondra select that took on Santos and shortly afterwards secured a move to Manchester United and later joining Johnny Giles at West Brom. In his club career he is probably most associated with Newcastle United, who he joined for £100,000 in 1978. He was hugely popular with the St. James’s Park faithful who dubbed him “Zico” and he got to play alongside the likes of Kevin Keegan and a young Chris Waddle during his time there. A move to New Brighton (a now defunct club on Merseyside) in the old Third Division North followed, as did the goals. He joined First Division Sheffield United in 1926 though he had to bide his time before getting a prolonged run in the first team. However he exploded into life in the 1929-30 season scoring 42 goals in 43 games and winning his first cap for Ireland (he scored twice in a 3-1 win over Belgium) that year as well. Dunne however wouldn’t be released by United for further fixtures (though he was allowed to play 7 times for the IFA selection) during his prolific scoring exploits over the next few years and he wouldn’t win a second cap until 1936 when he was playing for Arsenal by which stage he had fallen down the pecking order at Highbury due to the arrival of Ted Drake. A season at Southampton followed before Jimmy or “Snowy” as he was known to some returned to Dublin and to Shamrock Rovers in 1937 at the age of 32. It was while on the books of Rovers that Dunne would win nine of his 15 caps and score five of his international goals. Dunne still has by far the best scoring ratio for Ireland of any player who has scored 10+ goals at 0.87 goals per game and one wonders what his stats would have been like had he been made available to play for Ireland during his peak years at Sheffield United.

A move to New Brighton (a now defunct club on Merseyside) in the old Third Division North followed, as did the goals. He joined First Division Sheffield United in 1926 though he had to bide his time before getting a prolonged run in the first team. However he exploded into life in the 1929-30 season scoring 42 goals in 43 games and winning his first cap for Ireland (he scored twice in a 3-1 win over Belgium) that year as well. Dunne however wouldn’t be released by United for further fixtures (though he was allowed to play 7 times for the IFA selection) during his prolific scoring exploits over the next few years and he wouldn’t win a second cap until 1936 when he was playing for Arsenal by which stage he had fallen down the pecking order at Highbury due to the arrival of Ted Drake. A season at Southampton followed before Jimmy or “Snowy” as he was known to some returned to Dublin and to Shamrock Rovers in 1937 at the age of 32. It was while on the books of Rovers that Dunne would win nine of his 15 caps and score five of his international goals. Dunne still has by far the best scoring ratio for Ireland of any player who has scored 10+ goals at 0.87 goals per game and one wonders what his stats would have been like had he been made available to play for Ireland during his peak years at Sheffield United. witnessed in the League of Ireland and the most recent player to feature on this list. Crowe during the years of his peak was unplayable for opposing defences, he had strength, aerial ability and a cracking shot. He’s Bohs record league goalscorer, FAI Cup scorer and European scorer and was the League’s top scorer three years running. He’s also won 5 league titles (4 with Bohs, 1 with Shels) and two FAI Cups. At international level he featured against Greece under care-taker manager Don Givens and then again early in the reign of Brian Kerr in a cameo appearance against Norway.

witnessed in the League of Ireland and the most recent player to feature on this list. Crowe during the years of his peak was unplayable for opposing defences, he had strength, aerial ability and a cracking shot. He’s Bohs record league goalscorer, FAI Cup scorer and European scorer and was the League’s top scorer three years running. He’s also won 5 league titles (4 with Bohs, 1 with Shels) and two FAI Cups. At international level he featured against Greece under care-taker manager Don Givens and then again early in the reign of Brian Kerr in a cameo appearance against Norway. place that has given us plenty of them, including the Coads, the Fitzgeralds and the Hunts. Alfie’s father (Alfie Snr.) had been part of the first Waterford side to compete at League of Ireland level and at one stage formed an entire half back line for the club along with his brothers Tom and John in the 1930’s. Alfie Jnr. was born in 1939 and began his career with his hometown club before a somewhat peripatetic existence brought him to Aston Villa, where he would win his first international cap against Austria, and later to Doncaster Rovers where he would spend the majority of his stay in Britain. After seven years away Hale returned to Waterford where he was joined by Johnny Matthews and a little later by keeper Peter Thomas as part of a team that would dominate the League of Ireland, bringing five titles to the south coast between 1967 and 1973. Alfie’s final game for Ireland was as a Waterford United player in 1973 at the age of 34 when he came on to replace Don Givens in a 1-0 victory over a Polish side that had just finished ahead of England in World Cup qualifying.

place that has given us plenty of them, including the Coads, the Fitzgeralds and the Hunts. Alfie’s father (Alfie Snr.) had been part of the first Waterford side to compete at League of Ireland level and at one stage formed an entire half back line for the club along with his brothers Tom and John in the 1930’s. Alfie Jnr. was born in 1939 and began his career with his hometown club before a somewhat peripatetic existence brought him to Aston Villa, where he would win his first international cap against Austria, and later to Doncaster Rovers where he would spend the majority of his stay in Britain. After seven years away Hale returned to Waterford where he was joined by Johnny Matthews and a little later by keeper Peter Thomas as part of a team that would dominate the League of Ireland, bringing five titles to the south coast between 1967 and 1973. Alfie’s final game for Ireland was as a Waterford United player in 1973 at the age of 34 when he came on to replace Don Givens in a 1-0 victory over a Polish side that had just finished ahead of England in World Cup qualifying.