Jimmy Dunne stood on the pitch at the Weser Stadium, Bremen, May 1939, as the German anthem, complete with Deutschland über alles verses, echoed around the arena. The Swastika fluttered next to the Irish tricolour. Dunne was captaining Ireland that day and as a committed socialist, as a Republican who had been interned as a teenager, the fact that he has been told by his Association to give the Nazi salute grated deeply.

His teammate Joe O’Reilly recalled Dunne shouting to the rest of the side “Remember Aughrim, Remember 1916!” as they raised their arm. The packed stadium had heard a full two hour programme of stirring music and political speeches and were whipped into the appropriate delirious ferment. Further along the Irish team line, giving an awkward salute stood 20-year-old Dubliner, Johnny Carey of Manchester United.

Within months Carey had joined the British army and would be at combat against the Axis powers. As part of the Queen’s Royal Hussars he would see active duty in the Middle East and Italy. On his decision to enlist he stated that “a country that gives me my living is worth fighting for”. The match against Ireland was to be the last match that Germany would play before the outbreak of World War II less than four months later.

The Ireland team give an awkward fascist salute in Bremen.

So as Ireland prepare for their daunting challenge against the reigning World Champions in Gelsenkirchen let us remember this game that brought Ireland both praise and shame.

First it is important to note that the side that took on Ireland was not just a German team in the modern sense, as since the Anschluss of Austria the previous year that nations’ players were also called on to represent ” Greater Germany”. Among those in the German side that day was Wilhelm Hahnemann, born in Vienna he represented SK Admira a popular club in that city.

The FAI at the time were still in dispute with the IFA over the selection of players with both Associations selecting players from the whole island which in this case included Northerners like Sheffield Wednesday’s Willie Fallon born in Larne and Dundalk’s Mick Hoy from Tandragee lining out for the Free State.

The match in Bremen was to be the fourth that Ireland would play against German opposition in just four years. The Free State Association, still effectively ostracised by the Football Associations of the United Kingdom had to look to further shores in search of quality opposition, and this was regularly provided by the Germans.

In fact, given the massive political upheaval that took place throughout Europe during the 20s and 30s, it was not surprising that Ireland would find themselves competing against nations with far right and fascist governments. The Free State’s earliest games took place against Italy when they were under the rule of Mussolini, while the two games that preceded the game in Bremen were home and away fixtures against a talented Hungarian side; Hungary at the time was ruled by Miklós Horthy and his right-wing parliament which increasingly featured prominent anti-Semites.

When the Germans had last played against Ireland, in 1936 in Dalymount Park they had been well beaten. The Free State select running out comfortable 5-2 winners, with Oldham’s Tom Davis scoring a brace on his debut and Paddy Moore playing a starring role. On that occasion the Germany side had made the fascist salute and were joined by what can best be described as misguided members of the Irish sporting public (and perhaps some ex-patriot Germans?) who appear to have made the same gesture as a confused mark of respect to the visiting side.

By that stage there were already reports of the persecution taking place in Hitler’s regime but some felt that such reports were of dubious origin. Many Irish people remembered the fictional atrocities hyped by the British press that were attributed to German soldiers during the First World War and used as a recruiting tool in Ireland to get men to enlist, or indeed invented triumphs by Crown Forces during the Irish War of Independence. This was also the year of that grand Nazi propaganda exercise the Berlin Olympic Games; the view of the majority of the world seemed to be that sport should be wholly separate from politics. All the while Hitler wielded the global profile of the Games as a colossal example of Nazi soft power.

Theodor Lewald, a German protestant but one with well-known Jewish ancestry had been a key man in preparing Berlin for the Olympic Games. He had been head of the organising committee well before the Nazis cottoned on to the idea that the Games could be a great propaganda coup. When they decided to support the games with massive financial backing, Lewald’s Jewish ancestry became a useful defence to calls for boycotts of the games on the grounds of Germany’s discriminatory practices, even so he was eventually forced to step down from his role.

Avery Brundage, the head of the American delegation and later President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), had strongly objected to any boycott stating that he had been “given positive assurance in writing … that there will be no discrimination against Jews. You can’t ask more than that and I think the guarantee will be fulfilled”.

Only Spain (then on the brink of Civil War) and the Soviet Union (who had never participated up to that point anyway) would boycott the Games. Ireland, due to complex wrangling over the border issue could not field a team at the 1936 games. In this context it is perhaps somewhat understandable that Ireland would be so happy to play Germany in 1936.

However, by 1939, with Europe on the brink of war, and Germany being slowly ostracised after its 1938 conquest of Austria and the Sudetenland it is more difficult to ignore the political dimensions of the decision to play Germany and offer the Nazi salute.

Plaque commemorating the 1936 Olympic games featuring the name of Dr. Theodor Lewald

In his official report to the FAI Council the General Secretary Joe Wickham noted:

In Bremen our flags were flown though, of course, well outnumbered by the Swastika. We also, as a compliment, gave the German salute to their Anthem, standing to attention for our own. We were informed this would be much appreciated by their public which it undoubtedly was.

The German Sports Minister [Reichssportführer Hans von Tschammer und Osten] at the Banquet paid special tribute to our playing the match as arranged despite what he described as untrue press reports regarding the position in Germany and their intentions.

The Football Association were not the only ones to view the stories of German abuses with a certain measure of scepticism. The Irish Government held certain doubts as well, inherently distrustful as they were of British media reports, they were also being fed misinformation and racially motivated lies by their man in Germany, Charles Bewley.

Born into the famous Bewley coffee family whose iconic Grafton Street café still trades today, Charles was raised as a Quaker. However as a young man he went against his illustrious family and converted to Catholicism and became involved in politics, standing unsuccessfully for Sinn Féin in 1918.

By 1933 he had been appointed as Irish envoy to Berlin where he became an outspoken admirer of National Socialism and Adolf Hitler. He regularly reported back to Taoiseach Éamon de Valera that Jews in Berlin were not under threat but instead libelled the Berlin Jewish community, accusing them of all manner of vices.

Bewley’s actions also meant that those German Jews seeking a visa to come to the Irish Free State in order to escape the Nazi regime were generally refused, with fewer than one hundred Jews being granted visas during his time in Germany. De Valera finally dismissed Bewley in August 1939 but by then it was too late for many to escape.

The actions of men like Bewley can go some way to explain the certain level of scepticism which some in Ireland viewed reports of Nazi outrages. Joe Wickham as noted above seemed more concerned with showing due courtesy to their German hosts and was happy to repeat the line about the “untrue press reports” at the following Council meeting.

There is perhaps a certain obsequious Irishness evident here. With few international games available for the Free State association, who were effectively boycotted in senior internationals by the “Home Nations”, matches against a significant team like German were important for the Irish side and also for the association’s finances. A small, still fledgling association like Wickham’s was too beholden to the German.

It is also worth remembering that England playing in Berlin only a year earlier had given a Nazi salute before the game, although this was apparently done under protest from the players, especially from Eddie Hapgood of Arsenal who was England captain at the time. The English players only agreed when the British Ambassador to Germany Sir Neville Henderson informed them that a refusal to perform the salute could be the “spark to set Europe alight”. Interestingly Aston Villa, touring in Germany at the same time, refused to give the salute after their game against a German XI. The English side had also given a fascist salute again just days prior to Ireland’s match in Bremen ahead of their own game in Milan against Mussolini’s Italy.

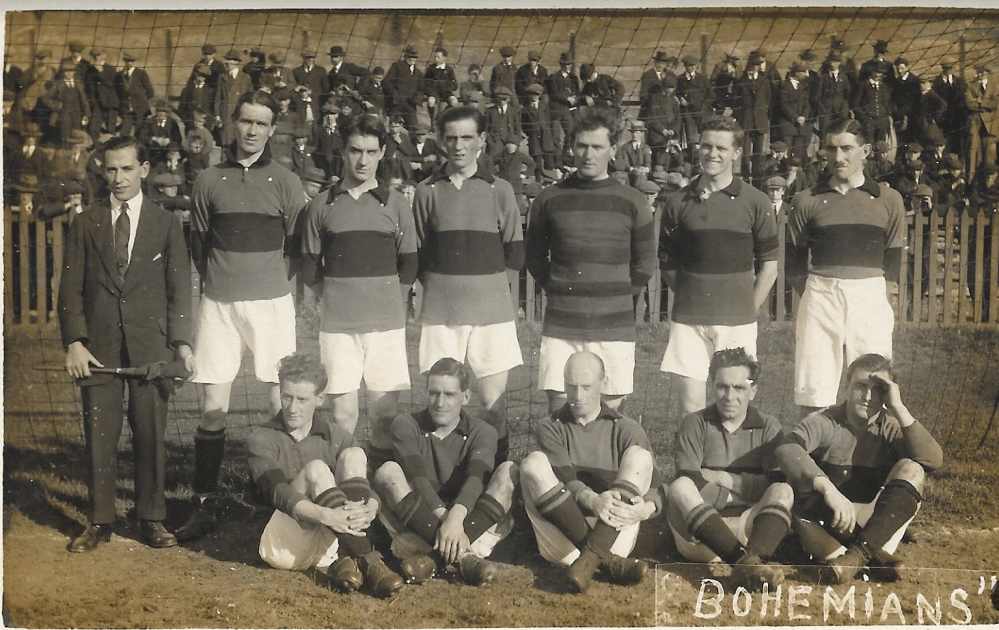

While England would go on to win their game 6-3 the game against Ireland would end as a one all draw. The Irish lined out with Southend’s George McKenzie in goal and a standard WM formation with a back line featuring William O’Neill, Mick Hoy (both Dundalk), Joe O’Reilly (St. James’s Gate), Matt O’Mahoney (Bristol Rovers), Ned Weir (Clyde) and a front five of Kevin O’Flanagan (Bohemians), Willie Fallon (Sheffield Wednesday), Jimmy Dunne (Shamrock Rovers), Johnny Carey (Manchester United) and Paddy Bradshaw of St. James’s Gate at centre forward.

The Germans apart from having the Austrian, Hahnemann in their ranks also featured world class players like their captain Paul Janes, rated as one of the world’s finest defenders, prolific goal-scorer Ernst Lehner was part of the forward line along with the man who would coach Germany to the 1974 World Cup, Helmut Schön. Organising things from the touchline was that legendary manager and creator of bon mots Sepp Herberger, who would eventually lead Germany to World Cup victory in 1954.

As described above over 35,000 people had crammed into the Weser Stadium from early on for the pre-match “entertainment” and had been suitably roused for the forthcoming match. While the German anthem and various martial airs had been blared out, the band present on the day had no sheet music for the Irish Anthem, according to journalist Peter Byrne, it was Joe O’Reilly who had once been a member of the Irish Army Band who stepped into the breach and sketched down the music for Amhrán na bhFiann from memory. The crowd was a then record attendance for the stadium and their enthusiasm seemed to have had the desired impact with Germany hitting the post through Hahnemann early on.

Ireland responded with some good play of their own as their “accurate passes and their head-work aroused the admiration of the crowd”, Dunne and Bradshaw were combining well and both forced good saves from keeper Hans Jakob. Disaster would strike though in the 34th minute, Jimmy Dunne, Irish captain and record goalscorer, was injured in a collision with defender Hans Rohde and had to be carried from the pitch. This misfortune was compounded only four minutes later when Helmut Schön scored the opening goal.

Ireland trailed one nil at the break and were forced to begin the second half with only ten men (still no substitutes in those days) and the Germans nearly grabbed a second goal through TuS Neuendorf forward Josef Gauchel. On the 55th minute Jimmy Dunne returned to the fray, going in at outside right meaning a move to centre forward for Kevin O’Flanagan, the 19-year-old was studying medicine in UCD and playing as an amateur for Bohemians, and was remembered as possessing one of the hardest shots in football , this move also allowed Paddy Bradshaw to withdraw to inside right.

The return of Dunne and the reshuffle in the forward line seemed to throw the Germans and the Irish improved in the volume and quality of their attacks, Carey came close to scoring before Bradshaw restored parity in the 60th minute with a powerful header from a Fallon cross. For the remaining half hour it was Jakob in the German goal who was the busier of the two keepers as the Irish pressed for the winner. The influential Kicker magazine stated “from a competitive point of view, there was no weak point in the Irish team, their only deficiency being a lack of precision in passing”.

A more than credible draw for the Irish in ominous circumstances, they were feted after their game by the German public, obviously impressed by the Irish play, and they were received by Nazi top brass at a banquet that night. The result would mark the best ever season of results in the short history of the Free State side and strange as it may seem they would probably have been looking forward to the following year’s fixtures.

Joe Wickham, flushed with the success of the Irish tour to Hungary and Germany was keen to organise fixtures for the coming seasons including matches against Spain, Italy and Romania. Of course war was to intervene and while the League of Ireland would continue the Free State would not play another international for seven years.

Young men like Carey and O’Flanagan would return for Ireland in the 1940s but the other nine men who took the field would never wear the green again. The greatest of these was Dunne, captain on the day and he had defied injury to finish the German game, his goalscoring record of 13 would stand for nearly 30 years. On the return journey to Ireland he was greeted in the port of Southampton and given a rousing salute from that city’s dockworkers, Dunne had played for Southampton for a year and his goals had saved them from relegation. Not something quickly forgotten by the working men of that town.

Because of those careers cut short, the ignominy of being required to make the salute, Johnny Carey’s desire to fight and the intermittently dangerous power of sport as propaganda do spare a thought for those men in Bremen when Martin O’Neill’s side line out in Gelsenkirchen.

Originally posted on backpagefootball.com in 2014