United Ireland v England and the token Welshman

In May 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain, the ten League of Ireland clubs ventured across the Irish Sea to join the festivities and take part in a series of exhibition matches against teams drawn from the Third Division (North) of the Football League. Of the opening round of fixtures involving the Irish sides only Bohemians would emerge with a victory, defeating Accrington Stanley (who are they?) 1-0, although the Bohs would lose their following two games against Oldham and Rochdale respectively.

This invitation was not limited to teams from the League of Ireland, Irish League sides also took part as well as teams from the Netherlands, Austria, Luxembourg, Belgium, Denmark and Yugoslavia. The Festival itself was held on the 100th anniversary of the Great Exhibition and was designed as a measure to showcase the best of British industry, art and design and perhaps most importantly to give a sense of hope and optimism to a nation still witness to the devastation of World War Two and still experiencing rationing, while hoping to rebuild. There was of course a footballing element and as well as the exhibition games played by visiting sides there were various other tournaments contested.

The Festival itself was hugely successful and it was estimated that as much as half the overall population of Britain visited a festival event during the summer of 1951. One man especially impressed was Juan Trippe, the Chairman of US Airline Pan Am who was apparently responsible for suggesting that Ireland might consider a similar festival event. Trippe and men like him were keen to increase trans-Atlantic passenger numbers on their airlines while the struggling Irish economy and Minister for Industry and Commerce, Seán Lemass were keen to elongate the short tourist season and increase visitor numbers. A plan was quickly put into action with An Tóstal (Ireland at home) being announced in 1952 with the aim of showcasing the country to foreign visitors, tapping into the dispora and beginning the tourist season earlier in Spring of 1953 rather than just in the traditional summer months. It was hoped that over 3,000 American tourists might visit for the festival as well as larger numbers travelling from Britain.

Sport played a key role from the outset with cycling, athletics, rugby, hockey, greyhound racing, tennis, shooting, badminton, chess and even roller hockey tournaments and exhibitions being held. Association football was not to be found wanting, for the first year of An Tóstal in 1953 the FAI arranged an Irish XI to take on a visiting Celtic side in Dalymount. The FAI selection defeating their Glasgow visitors 3-2, while there was also an Inter-League game arranged against the Irish League a few days later. This was the first meeting of the representative league sides in three years and it was hoped the match might ease relations between the FAI and IFA which had been strained yet again during qualifying for the 1950 World Cup with the IFA trying to select players born outside the six counties. It was only the intervention of FIFA that finally ended the practice of players representing both “Irelands” that had persisted for over twenty years.

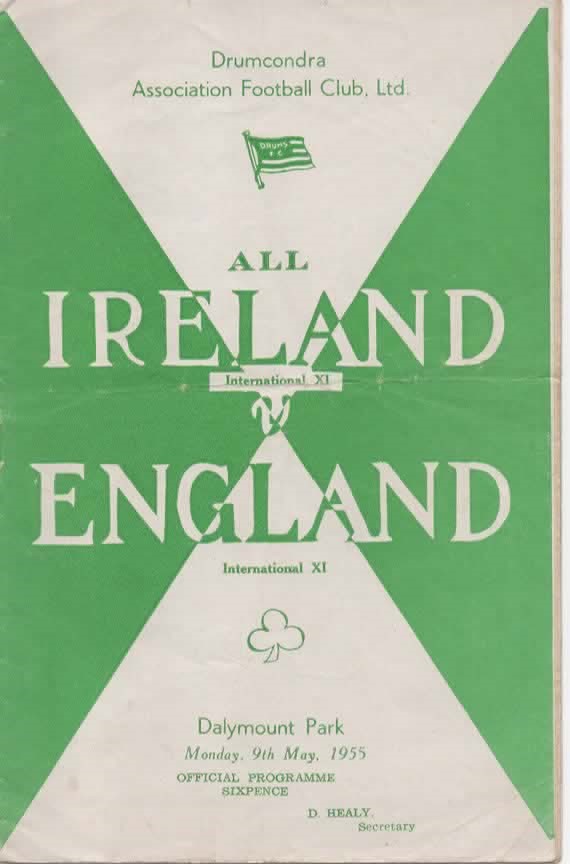

An Tóstal would return again in subsequent years and it was in 1955 that an intriguing fixture was announced featuring and “All Ireland” side who would take on and England XI. This match was the brainchild of Sam Prole, an FAI official and owner of Drumcondra FC, who had also previously had a long involvement with Dundalk FC. The game was to play the dual role of being a focal point for football during a busy end of season period and part of the An Tóstal events and it was also to act as a fundraising event for investment into Tolka Park, home of Drumcondra FC.

The Prole family had taken over Tolka Park just a couple of years earlier and had seen almost immediate success with an FAI Cup win, they had also invested in the first set of permanent floodlights at a League of Ireland ground and had introduced other stadium innovations such as pitch side advertising boards as well as purchasing the house at the Ballybough end of the ground with a view to increasing stadium capacity. However, in 1954 Drumcondra and the North Strand suffered extreme flooding with the Tolka River bursting its banks and causing significant damage to the stadium. The Proles had ambitious plans for the club but also knew that an insurance settlement from the flood only covered a portion of the costs of repair and they need to generate additional revenue.

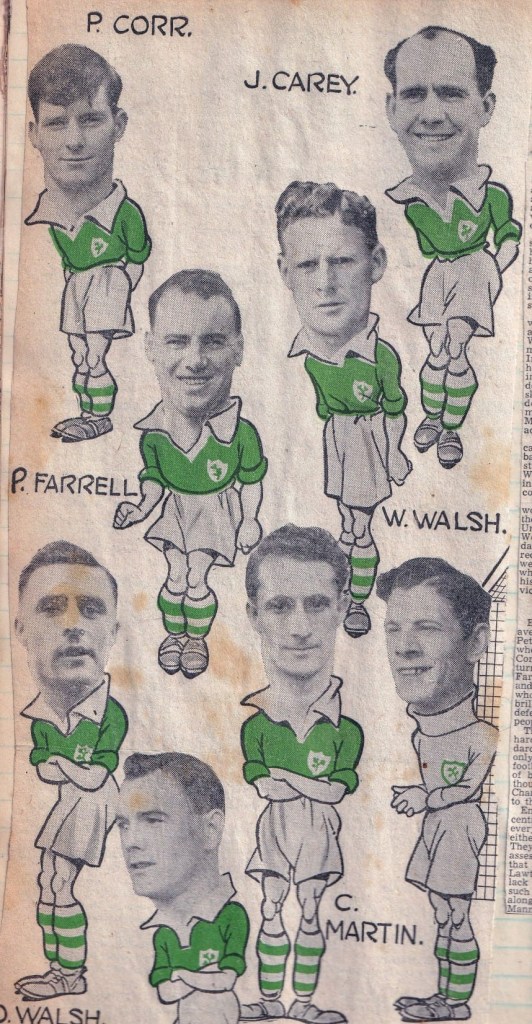

Dalymount Park, the largest football ground in the city, was chosen as the venue for this high-profile fundraising game and Prole went about putting together a pair of squads designed to appeal to the interests of the Dublin football public. The match programme for the game referred to the team as the “England International XI” and the “All Ireland International XI” however in various sections of the Press the teams were variously referred to as All Star XIs an “Old England XI” and also, trading on the name recognition of their star, the “Stanley Matthews Old England XI”. As the names suggest it was something of a veteran side brought over, the side being up of players the wrong side of thirty, while Matthews himself had just turned 40, though he was still a current English international. Nor were the England international side all English! In the side at centre-forward was Cardiff City’s Welsh international striker Trevor Ford.

The All-Ireland side was more mixed in ages, though several veterans still featured in the ranks, including one of the biggest draws Peter Doherty, the manager of Doncaster Rovers . Doherty had been a League winner with Manchester City before the War and a Cup winner with Derby County after it. He’d also been capped sixteen times by the IFA and was considered on of the greatest inside forwards of the 1930s and 40s. The advertising material in the run-up to the game focused on the presence of “Peter the Great” and “Stanley the Wizard” in the opposing sides.

As often happened with these games there were some last minute changes, the team named as travelling to Dalymount, and listed in the match programme was as follows; Ted Ditchburn, Alf Ramsey (both Tottenham Hotspur), Tom Garrett , Harry Johnston (both Blackpool), Neil Franklin (Hull City), Allenby Chilton (Grimsby Town), Stanley Matthews (Blackpool), Wilf Mannion (Hull City), Tommy Lawton (Arsenal), Jimmy Hagan (Sheffield United), Jack Rowley (Plymouth).

However, Mannion, Lawton and Hagan had to cry off for various reasons and at short notice they were replaced by Charlie Mitten of Fulham, Bobby Langton of Blackburn Rovers, a former England international. Replacing Lawton at centre forward was Trevor Ford of Cardiff City. As mentioned Ford was also the Welsh international centre-forward and as such this “England” side’s attack was led by a man from Swansea. While the side was on the older end of the age spectrum for professional footballers the entire XI apart from Mitten had been capped, and Ditchburn, Matthews and Ford were still current internationals.

Several of the Blackpool team who had won the FA Cup in 1953, famously dubbed the Matthews final, also appeared. Alf Ramsey, Spurs reliable full-back had won 32 caps for England but would find his greatest fame as a manager, first leading unfancied Ipswich to their only league title and then taking England to World Cup victory. The “England” side also featured several players who were somewhat infamous, both Mitten and Franklin were part of the “Bogota bandits” who left their club contracts in England and went to Colombia to play in the non-FIFA recognised league there due to the high wages on offer.

At the time the maximum wage which capped players salaries was still very much in force. Franklin, one of the greatest centre-halves of his generation never won another cap after his Colombian soujourn, while Mitten, who missed out on much of his early due to World War Two was never capped despite being a successful and popular winger for Manchester United and Fulham. A year after the game in Dalymount Trevor Ford would reveal in his autobiography that during his time at Sunderland he had been in receipt of under the counter payments to circumvent the maximum wage. He wasn subsequently suspended and announced his retirement, however changed his mind and moved to the Netherland where his ban could not be enforced and joined PSV Eindhoven.

In the Irish side there was a breakdown of six players born south of the border and five from the north, although like the English side there were late changes, Aston Villa’s Peter McPartland being unavailable he was replaced by his club and international teammate Norman Lockhart. The Irish stating XI read as Tommy Godwin (Bournemouth), Len Graham (Doncaster Rovers), Robin Lawlor (Fulham), Eddie Gannon (Shelbourne), Con Martin (Aston Villa), Des Glynn (Drumcondra), Johnny McKenna (Blackpool), Eddie McMorran (Doncaster Rovers) Shay Gibbons (St. Patrick’s Athletic), Peter Doherty (Doncaster Rovers), Norman Lockhart (Aston Villa).

Sam Prole obviously could rely on the services of his own players like Des Glynn, as well as former Drumcondra men like Con Martin and Robin Lawlor. As mentioned the connection with Doncaster Rovers through manager Peter Doherty, who was also manager of Northern Ireland likely helped secure the services of several other players.

The match proved to be a success in terms of the turnout and entertainment value, 24,000 turned up in Dalymount Park on the 9th of May 1955 for a goal-fest. The main plaudits were rained on Stanley Matthews for his exhibition of wing play, but the entire “England” forward line drew praise from the media reports, Trevor Ford being referred to as the “Welsh wizard among the Saxons” while he scored twice for England. In defence Neil Franklin and keeper Ted Ditchburn were also complimented. Ditchburn was lauded as the best keeper in England despite the fact that he conceded five on the day, Tommy Godwin in the Irish goal came off on worse as the hosts lost 6-5.

There was also praise for several of the Irish performers, despite having hung up his boots two years earlier the technique of Peter Doherty was still remarked upon, however it was Doncaster’s Eddie McMorran who drew the most praise and scoring two of the Irish goals. The press raved about the game, the Evening Herald declaring, in terms of exhibition matches “one of the finest ever seen at Dalymount Park” and again praising Matthews who it described as “being in peak form”. The Irish Press was similarly effusive, leading with the headline “Exhibition Treat Thrills Crowd – Stars Give a Soccer Lesson”. The healthy gate who turned up to see the star names no doubt helped the Prole family in the repair and upgrading work being carried out a short distance away at Tolka Park.

This marked a busy time for Dalymount, as days later there was another large attendance for An Tóstal events, with 15,000 turning up for a fireworks display which climaxed with “glittering reproduction of the Tostal harp in fiery gold. Underneath were the words : ” Beannacht De libh.” The young crowd left delighted although there were complaints from residents who were unaware of the event and were frightened by the unexpected noise.

Bouyed by the success of the 1955 match Sam Prole set about organising another All-Ireland v England match for the following year, though this time without the fundraising for Tolka tagline. Once again there was a high-profile selection of English veteran stars recruited and once again there was a cross border make-up to the Irish side. Though for 1956 it was much more weighted to the north with ten of the starting eleven being IFA internationals with only Pat Johnston, a Dubliner then plying his trade for Grimsby Town, coming from south of the border.

Several faces from the previous year’s game returned, including Peter Doherty and his Doncaster Rovers contingent which now included a young goalkeeper named Harry Gregg who would find fame at Manchester United, both on the pitch, and off it as one of the heros of the Munich air disaster. Once again Aston Villa’s Peter McParland was slated to appear but had to cry off, with once again his clubmate Norman Lockhart replacing him. There was also the considerable draw of two stars of Glasgow Celtic, Charlie Tully and Bertie Peacock. Tully, especially was a crowd favourite known for his amazing ball control, on-field trickery and cheeky personality. Such was his popularity among the Celtic faithful there were descriptions of “Tullymania” and his fame spawned an entire trade in Tully products and souveniers.

There were also returning stars from the “England” side that had played in the first game in Dalymount such as Tom Garrett of Blackpool and the “Welsh wizard” Trevor Ford, both late call-ups after Joe Mercer and Stan Mortenson were forced to pull out. The full teams were as follows:

“All-Ireland” – Harry Gregg (Doncaster Rovers), William Cunningham (Leicester City), Len Graham (Doncaster Rovers), Eddie Crossan (Blackburn Rovers), Pat Johnston (Grimsby Town), Bertie Peacock (Celtic), Johnny McKenna (Blackpool), Charlie Tully (Celtic), Jimmy Walker (Doncaster Rovers), Peter Doherty (Doncaster Rovers), Norman Lockhart (Aston Villa)

“England” – Sam Bartram (York City), George Hardwick (Oldham Athletic), Bill Eckersley (Blackburn Rovers), George Eastham Snr. (Ards), Malcolm Barass (Bolton Wanderers), Tom Garrett (Blackpool), George Eastham Jnr (Ards), Ernie Taylor (Blackpool), Trevor Ford (Cardiff City), Jackie Sewell (Aston Villa), Jimmy Hagan (Sheffield United).

While there were well known veterans in the England team, Hagan was 38 and Sam Bartram, a Charlton legend and one of the most popular goalkeepers in football, was over 40 and had moved into management at York, were in the side there were also several younger players such as Johnny Wheeler and Ronnie Allen who were under the age of 30 and were due to feature but they both pulled out and were replaced by the father and son duo of George Eastham Senior and Junior. In the build up to the game much was made of the value of the team to be put on the pitch with the figure of £250,000 mentioned. In fact, in Jackie Sewell and Trevor Ford, there were two players who had broken the British transfer record over the past six years.

It seems the crowd wasn’t as strong as the one from the previous year, attendance figures not being shared, but newspaper reports variously describing it as a “good” or “medium” crowd, it was also noted that the quality of the display was at a lower lever than the 1955 game, with this match having a more prounounced “end of season friendly” feel to it. The Irish Press called the game an “end of season frolic” while most reports did note the slower pace of the game and the lack of hard tackling, they were quick to praise the style and technique of the players on display. Once again the crowd were treated to a glut of goals, though the score wasn’t a close as the match a year earlier, Ireland lost 5-3 though reports state that this wasn’t a true reflection of the visitors superiority. Once again Trevor Ford was one of the stars while Villa’s Jackie Sewell also earned rave reviews. For the Irish side it was much more the Charlie Tully show, with him seeming to be the one player who was fully committed to the game, being described as a ball of energy and entertaining the crowd with his skills which prompted cries of “Give it to Charlie” from the terraces when Ireland were in possession.

The younger George Eastham was also impressive for the English side, still only 19 Eastham had been a stand out player in the Irish League for Ards where his then 42 year old father was player-manager, before the year was out Eastham Jnr would sign for Newcastle United, and later his subsequent, protracted transfer to Arsenal, and court case would win significant change for players rights in English football, doing away with the old “retain and transfer” system clubs still held player’s registrations, even when the player in question was out of contract. He would enjoy a long and successful career and was a squad member of the England side which would win the World Cup in 1966.

Eastham Jnr. would open the scoring for England after Ireland took an unexpected lead through Walker, braces from Ford and Sewell rounded off the scoring for the English side, while the veteran Doherty with a penalty and Norman Lockhart scored Ireland’s other two goals. While the match was not as much of a success as the 55 game there was still praise for Sam Prole for taking the initiative to organise the game and for contributing on behalf of the footballing community to the Tóstal festival.

One possible reason for a smaller crowd in 1956 was not just the different line-ups, late withdrawals, or absence of Stanley Matthews, but also the sheer volume of other exhibition matches, often involving the same players, taking place at the time. Within days of the “All Ireland” v “England” game in May of 1956 there was an Irish youth international against West Germany, followed the next day by a combined Ireland – Wales XI against an England-Scotland XI, both taking place in Dalymount Park. Trevor Ford would feature for the Ireland/Wales side alongside Ivor Allchurch and local Cabra lad Liam Whelan, then making his name at Manchester United.

These games came just days after a Bohemian Select XI took on a side of Football League managers in an entertaining 3-3 draw in aid of the National Association for Cerebal Palsy. Among the Managers XI were players familiar to those who had attended the “All Ireland” games, such as Charlie Mitten, Trevor Ford (again), Peter Doherty (again!) as well as the likes of Bill Shankley and Raich Carter. There was perhaps a law of diminishing returns as despite the reports claiming the game was a highly entertaining spectacle and the associated good cause receiving the benefit, the crowd was descirbed as “disappointing”.

While the Shamrock Rovers XI match against Brazil in 1973, essentially a United Ireland side in all but name, is well known, and its 50th anniversary was marked last year in several quarters, these games in the 1950s are less well remembered. There are perhaps a number of reasons for this, for example, up until 1950 it was common practice for both the IFA and FAI to select players from either side of the borders and more than forty players were capped by both Associations. In this situation “All Ireland” representative sides were not all that uncommon, even if this did occasionally lead to tensions and even threats against players.

In the 1950s, Sam Prole, a key figure in the League of Ireland and the FAI was the driving force behind the matches, similar to the role played by Louis Kilcoyne in the 1973 game against Brazil, and similarly again there was the involvement of a national team manager, Peter Doherty in the 1950s and John Giles in the 1973 game. However, it seems that while the games in 1955 and 1956 used the title Ireland or All Ireland and the 1973 game was compelled to go under the Shamrock Rovers banner, the political situations were quite different. The 1973 game was played against the backdrop of one of the worst years of violence during the troubles, at the time the IFA were playing “home” matches in various grounds around England while a year earlier the 1972 Five nations rugby championship could not be completed as Scotland and Wales had refused to travel to Dublin, highlighting safety concerns.

There seemed to be a concerted effort by players involved in the 73 game to offer a counter narrative and most spoke of being in favour of a 32 county Irish international side. The games in 1955 and 56 lacked this political backdrop, the ill-fated IRA border campaign wouldn’t begin until the winter of 1956, and the stated aim seemed to be a novelty factor and curiousity element as can be seen with the other types of exhibition matches played at the time. There was no sense in any reportage that the games in 55 and 56 were trying to make a political point, they were fundraisers for Tolka Park initially, and a contribution by Irish football to fill a programme for the An Tóstal festival.

Though less than 20 years apart the football landscape was very different between 1955 and 1973. By 1973 European club competition was the norm, when it was only in its earliest phase in 1955 and lacked Irish or English participants. By 1973 colour TV had arrived and there was a massive increase in television set ownership in Ireland through the late 1960s. Where once stars of British football could only be seen in international or exhibition matches, or in snippets on newsreels, now they could be watched every Saturday night on Match of the Day.

While vestiges of An Tóstal live on today, it’s still celebrated in Drumshambo, Co. Leitrim for example, and we can credit it with the genesis of the likes of The Rose of Tralee, The Tidy Towns competition, the Cork Film Festival and Dublin Theatre Festival, one legacy it didn’t leave is a united, 32 county, Irish football team. Perhaps when Ireland is next on our uppers, and we have to reinvent a reason to convincea tourist diaspora to flock home to the old sod, we’ll hold some matches in Dalymount and unite the nation again?

With thanks to Gary Spain for sharing images of the match programmes for the 1955 and 1956 games.