Jack O’Donnell – the Dolphin trawling the seas

As excuses go for missing training it was at least original. Being absent because you were caught in storms aboard a fishing trawler off the coast of Iceland and at any moment feared that you’d be washed overboard to a watery grave. This was the excuse offered by Jack O’Donnell, full-back for Blackpool FC in 1932, when they were still a top-flight side. It wasn’t to be O’Donnell’s first brush with authority, nor his last. This is the story of how a talented footballer went from being a League champion with Everton to making intermittent appearances for Dolphin FC and Reds United in the League of Ireland either side of a stint in prison.

O’Donnell was born in Gateshead in March 1897, the son of John and Grace O’Donnell. John was a labourer from Newcastle, though the O’Donnell surname does suggest an Irish lineage some way back in the family. By the age of 14 young Jack was already working as a driver in a coal mine. Like many young miners-cum-footballers in the north east of England he began playing with his local colliery team, Felling and then later with Gateshead St. Wilfrids, before being signed by Darlington in 1923. At the time Darlington were in the Third Division North, and were on the lookout for a stiker, however a series of injuries meant that O’Donnell was pressed into service on his debut as a left back, the position that he was to make his own over the coming two seasons.

In early 1925 Darlington were drawn against Cardiff City in the first round of the FA Cup. While Cardiff would ultimately prevail, and make it all the way to the final that year, Darlington did manage to take them to two replays with back-to-back 0-0 scorelines. O’Donnell was especially impressive in these games and drew the attention of Everton who signed him just weeks later in February 1925 for a fee of £2,700, huge money at the time for a defender, especially one playing in the Third Division and was at the time far and away the record fee ever received by Darlington.

One issue of note however, is that at the time of signing for the Toffees, O’Donnell was a month shy of his 28th birthday but the newspapers at the time of the transfer list him variously as 20 or 21 years of age. A journalistic mistake or a case of O’Donnell shaving a few years off his actual age? He certainly wouldn’t be the first or last footballer to attempt it if this was the case.

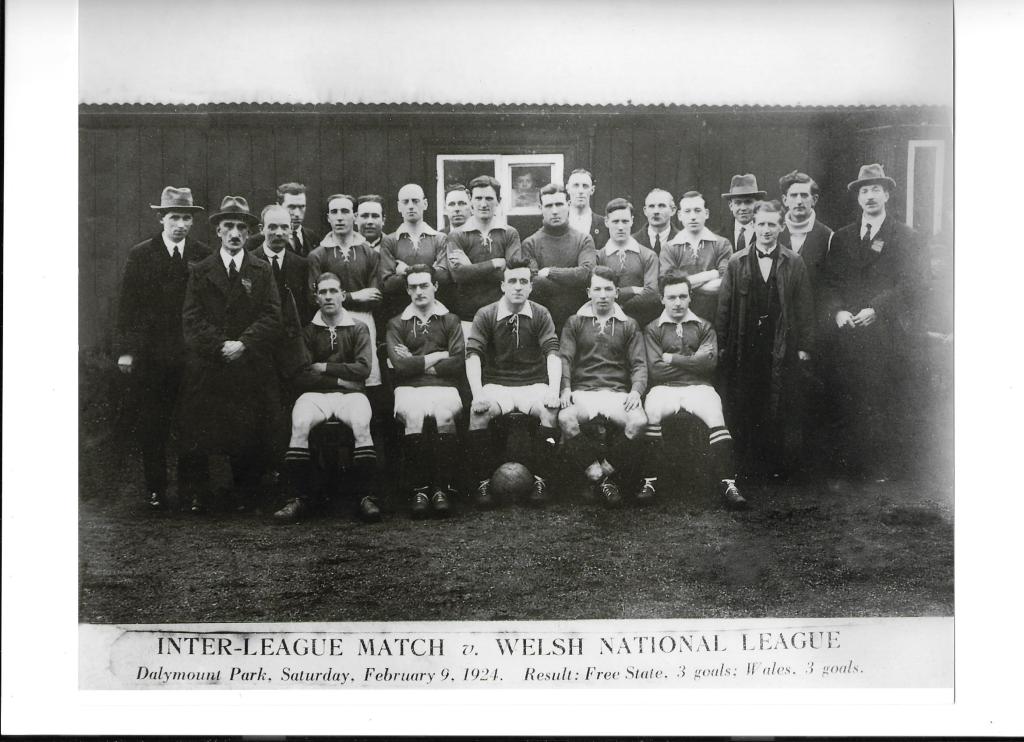

O’Donnell quickly made the Everton first team, although his versatility was occasionally to his detriment, twice in his early days he ended up going in goal to replace an injured goalkeeper as substitutions were not yet allowed. He also ended up featuring as an inside-left for the Toffees and while ‘Dixie’ Dean was clearly the first choice centre forward O’Donnell did contribute five goals in the 1925-26 season when pressed into the forward line. While he made 27 and 24 League appearances respectively in his first two, full seasons with Everton there is a sense that his adaptability stopped him from cementing his place in the team. That was to change for the 1927-28 season though, O’Donnell, along with Scottish winger Alec Troup, were the only two players to feature in all 44 games for Everton that season (42 League, 2 FA Cup) as Everton, propelled by the brilliance of ‘Dixie’ Dean who scored 60 League goals, won the League Championship.

O’Donnell the ever-present, won plenty of praise that season, he was a physically tough player but with surprising technical skill, his bravery and fearlessnesss in the tackle also marked him out and there are numerous reports of last ditch tackles saving the day at Goodison Park and elsewhere.

It was also during that league winning season that Jack married Margaret Butcher, with the first of their two children, John, being born the following year. It seemed that everything was going well for Jack. For the following two seasons he was a first team regular for Everton and while they won the Charity Shield the following year there was a drop to 18th in a 22 team league. Worse was to follow the next season (1929-30) as Everton finished bottom and were relegated. In August of 1930, as Everton were facing into the prospect of a season in the Second Division there was a note at a club board meeting mentioning O’Donnell as “suffering from a disease of owing to his own misconduct” and being suspended for 14 days. He would never play for the Toffees again.

Rather than spend a full season in Division Two, especially having fallen from favour with the board, O’Donnell joined Blackpool in Division One for a fee of around £1,500 just after Christmas 1930, as the seaside club aimed to stave off a relegation battle of their own. Blackpool did manage to narrowly survive that season with O’Donnell installed at full-back and he even was named as team captain. O’Donnell and was a regular starter for the rest of the season as Blackpool finished 20th out of 22 teams, with only two sides relegated Blackpool survived by a single point as Leeds and Manchester United dropped into the second tier.

The following season was to be a similar experience for Blackpool, once again finishing 20th and avoiding the drop by a single point. Again, O’Donnell was a regular, playing 31 out of 42 League games, however there was significant drama for Jack off the pitch.

In November of 1931 O’Donnell was suspended by Blackpool for fourteen days for an unnamed “breach of discipline”, he had also been stripped of the club captaincy just weeks beforehand. When interviewed later in 1933 for the Topical Times O’Donnell gave a robust, if rambling, defence of himself. In an interview which featured allegations of club directors taking backhanders, O’Donnell alleges that his initial suspension at Blackpool resulted from false rumours being spread about him by “somebody with a nose for trouble-making and a character which didn’t have truth in his make up” who made the claim that O’Donnell was going out and getting drunk every night. O’Donnell denied this but said that these allegations had reached the ears of the Blackpool directors who called him for a meeting. O’Donnell recounts that he was “furious that they even listened to such tales” and that as a result he “said things he didn’t mean”. The outcome was another suspension by the club.

It is however, the way in which O’Donnell chose to spend his suspension that gained him most notoriety. Due to return to training in early December O’Donnell was a no-show at the day he was due back. His landlady, and his friends in the local club where he socialised didn’t know where he was but his landlady did mention that O’Donnell had previously expressed a desire to become a fisherman. A man answering to O’Donnell’s description and wearing a pair of plus fours was seen boarding the trawler Cremlyn in the port of Fleetwood in the company of the trawler’s cook.

Jack O’Donnell had indeed gone to sea! Speaking to the media later in December, after he’d returned to dry land he gave the somewhat implausible story that he had simply been talking to the ship’s cook who was a friend of his, had boarded the Cremlyn with no intention of sailing, but without realising the boat had pulled away from shore. O’Donnell was also quick to deny the allegations that he had claimed he was done with football and was planning on pursuing life as a fisherman.

This rather thin excuse is contradicted by O’Donnell himself in the 1933 Topical Times interview when he says that being suspended and having little to do, that he was invited to go sailing on the basis that it was to be a short trip and that he would be back in Blackpool in plenty of time ahead of the lifting of his suspension. However, these plans were waylaid by Poseidon when, off the coast of Iceland the Cremlyn “ran into one of the biggest storms ever seen in the North Atlantic” according to O’Donnell. He claimed that the lifeboat was washed away in the storm and he feared that “every minute would be out last.”

O’Donnell did of course make it back to dry land, but unimpressed with his explanation the board of Blackpool, still fighting off relegation, gave him a further fourteen day suspension. On this occasion O’Donnell had the good sense to remain off the high seas. Jack’s aquatic adventures had further reprecussions for him off the football field, as the New Year turned to January 1932 he found himself served with a court order by his, now estranged, wife Margaret. While Jack was living in Blackpool, Margaret was still living in Gateshead with their son John. There had been a legal agreement in place since July of 1931 that Jack would pay £2 a week in maintenance to his wife, but that around the same time as the trawler incident these payments had ceased.

It was at this point that Margaret declared that she was “absolutely destitute” and had to “apply for relief”, meaning that she had to seek the limited form of social welfare available under the “poor laws” that existed at the time. Representatives of Blackpool FC pleaded with Margaret to cease proceedings in the case, promising a £4 postal order and £2 a week as long as he was employed at Blackpool and further stating that “Jack is making a big effort to make a man of himself and we are doing all possible to assist him.”

The case was adjourned for a week and when it was eventually heard in Gateshead a court order of £2 a week maintenance for his wife and son was made against Jack. Margaret mentioned a particular personal cruelty from Jack, despite being in Newcastle for three days for a cup game against Newcastle United (which was taken to a replay which Blackpool lost) in the week before the hearing, Jack made no effort to get in touch with his wife or three year old son.

O’Donnell finished out the season for Blackpool as they clung on to secure their top-flight status, but there was further drama during the summer as once again Jack went missing, this time in July during pre-season training. Blackpool quickly sought to have O’Donnell suspended by the FA, who duly obliged. With the new season on the horizon Jack O’Donnell found himself in an unevniable position, suspended from playing football but with Blackpool still holding his registration and hoping for some return in terms of a transfer fee for their errant star. The club denied that a transfer was forthcoming but there was still a protracted saga as Hartlepools United, then in the Third Division North, sought to sign O’Donnell. Hartlepools were managed by Jackie Carr, a former England centre half who had briefly played with O’Donnell at Blackpool towards the end of his own career. He clearly believed that his former teammate and powerful full back still had something to offer despite his many off the field issues and disappearing acts.

A prolonged transfer saga was finally brought to an end when Hartlepools paid a fee in the region of £500 for O’Donnell’s services. Blackpool placed certain conditions on the transfer and successfully requested the FA to lift the player’s suspension so that he could move to the County Durham club.

Jack was once again a regular, playing out the season with Hartlepools, and once again he was made club captain making 28 league appearances, scoring twice as they finished lower mid-table in Division Three. It was to be his only year with them as with the season coming to a close he was transfer listed in May 1933 and by August of that year Jack had joined Wigan in the Cheshire League where he was once again made club captain on his arrival.

This return to football wasn’t quite guaranteed as during the summer of 1933 Jack once again took to the seas, taking a job as a steward on an ocean liner sailing between Liverpool and Montreal. In the Topical Times interview he recalls playing football for a team made up of the ship’s crew, playing against barefoot teams in the Canary Islands and against American and Canadian sides, recounting the physicality of the game as played in America (which is saying something considering the physical nature of O’Donnell’s own game but also tallies with other descriptions of the extremely physcial nature of the game in the United States) as well as describing a sporting encounter with Everton legend of the teens and twenties, Sam Chedgzoy who had relocated to Canada.

Despite being installed as captain and some encouraging early performances at Wigan, Jack was once again in trouble with the club heirarchy after only a couple of months. By October 1933 he had pulled yet another of his “disappearing acts” and there was speculation on behalf of Wigan Athletic that his well-known wanderlust and love of deep-sea fishing had gotten the better of him and that he had once more gone to sea, which to some extent he had, bacause Jack was with the Dolphins. He had crossed the Irish sea to sign with League of Ireland side Dolphin, located in the south Dublin suburb of Dolphin’s Barn.

Dolphin FC had finished the previous season as FAI Cup runners-up and were under the tutelage of player-manager Jerry Kelly. The Scottish defender/midfielder had enjoyed a successful career in England winning a league title for Everton alongside Jack O’Donnell and it is likely that his former teammate was responsible for Jack’s trip to Dublin. While Jack had been suspended by Wigan, the fact that they were a non-league club and the somewhat fluid nature of transfers between British and Irish teams at the time meant that transfer rules were less hard and fast, however it still took a couple of weeks for clearance and paperwork to be finalised by Wigan to allow Jack make his League of Ireland debut for Dolphin.

O’Donnell impressed in his first game for Dolphin, a 3-0 win over Cork Bohemians on 26th November 1933, he was praised for his “powerful kicking and positional play” and got on the scoresheet with a penalty after a Cork handball. It is obvious that O’Donnell had impressed not only at the back but with his attacking play and a move to centre-forward, where he had previously played on occasion for Darlington and Everton, was planned for the next game against Shelbourne. This would allow a return to the defence of Dolphin’s international pairing of Larry Doyle and George Lennox. Of course, this wasn’t to be, Jack O’Donnell had pulled yet another one of his “disappearing acts” going missing for both the Shelbourne game and the subsequent match against Bohemians.

By the time O’Donnell returned in mid-December after dealing with unnamed “business” Dolphin had signed a new striker in the form of Jimmy Rorrison who had joined them from Distillery. Rorrison, something of a journeyman striker in the Scottish and English Leagues had impressed at Cork the previous season and took over the centre forward berth with O’Donnell continuing in his favoured role at left-back.

Dolphin cruised to an easy 4-1 victory in their next match with Bray Unknowns with O’Donnell scoring another penalty and his overall display being described as “polished and clever”. O’Donnell featured in a run of games for Dolphin over the Christmas period and into the New Year of 1934, scoring a third penalty in a 2-1 defeat to Shamrock Rovers in January. There was a return to form the following week in the opening round of the FAI Cup, as Dolphin were drawn in something of a local derby with fellow southsiders Jacobs. O’Donnell was installed as centre-forward in place of Rorrison who was released after only a month at the club. O’Donnell scored twice from open play as Dolphin swept to a facile 5-0 over the Biscuitmen which was followed by a victory over Queen’s Park (from the Pearse Street area of the city) after a replay in the second round. All of a sudden Dolphin were into the Cup semi-finals.

However, the cup run seems to have distracted from their league form and Dolphin slumped to a 2-0 defeat to bottom side Cork Bohemians with O’Donnell being utilised as an inside-left to little effect. This slump in form continued for Dolphin as they were beaten in a dull game 1-0 by St. James’s Gate in the Cup semi-final, Billy Kennedy scoring the decisive goal as Jack O’Donnell was returned to his more usual position of left-back. O’Donnell continued as a regular for the remainder of the season, and although Dolphin’s form was patchy he did win praise for his displays, mostly in the full back position although he did score his fourth, and final, league goal for Dolphin in March 1934 as a centre-forward in a resounding 3-0 win over Dundalk in the final game of the season.

Dolphin finished fifth that season and had made the semi-finals of the FAI Cup, however they had probably hoped for a little bit more having recruited heavily from outside the league, including the signing of O’Donnell. Dolphin had led the way in the League in the recruitment of cross-channel players and were known as one of the clubs in the League of Ireland who were prepared to pay higher wages to bring talent across the Irish Sea to Dublin. This also influenced their choice of coaches such as Arthur Dixon who would join the coaching team at Rangers and bring the young Dolphin star Alex Stevenson with him, and Dixon’s eventual replacement, Jerry Kelly who brought his former teammate O’Donnell to Dublin.

Reports stated that Jack had returned to Blackpool for the summer months, he was gone from Dolphin for their League of Ireland Shield campaign and missed the friendly match against Notts County arranged as part of Willie Fallon’s move from Dolphin to the Magpies. However, it wasn’t to be a relaxing summer on the beaches of Lancashire for Jack, in May 1934 he faced another summons from his wife Margaret for once again abandoning her and his family as Margaret had once more been forced to go to the “Public Assistance Committee” to makes ends meet. Jack was now a father of two, as a daughter, Kathleen had been born earlier that year. In her statement Margaret recounted that he had briefly returned to her after being suspended by Wigan and that later that year his “disappearing act” from Dolphin in November had seen him briefly return to his family in Gateshead. After finishing with Dolphin in March he seems to have ended up in Blackpool where he claimed he was looking for work on the town’s pleasure beaches. At the court hearing in Gateshead he was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment.

Upon Jack’s release at the end of June the court ordered that he pay 25 shillings a week in maintenance to his wife and growing family. Faced with this challenge it is unclear what Jack did for the remainder of his summer however he reappears in media reports in September with the news that he has signed for non-league side Clitheroe. Although 37 years of age by this stage, (if his clubs were even aware of his real age), it was to football that he returned yet again to make a living. As always with Jack it wasn’t plain sailing, having only played once for Clitheroe there was an objection to his registration from Dolphin, he remained their player and they claimed that he had been suspended by them and as such couldn’t turn out for another team. This would suggest that Jack’s return to Britain at the end of the previous League campaign wasn’t something that had been agreed with Dolphin.

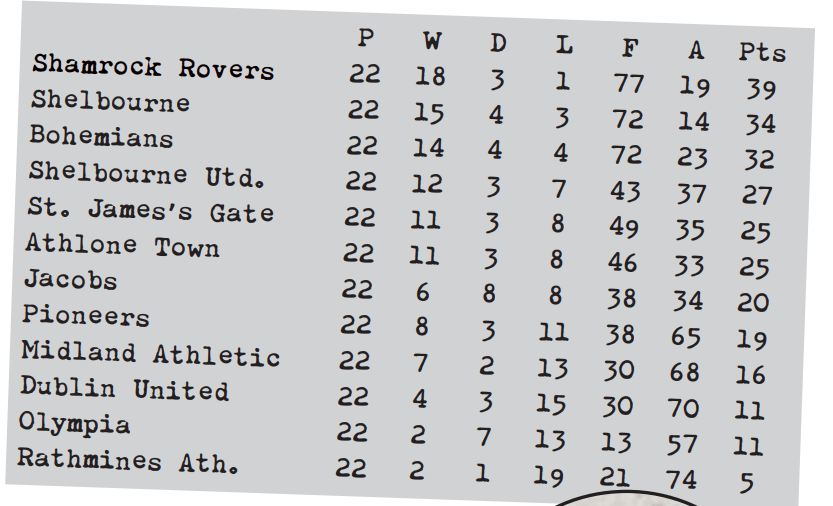

Frustated in these attempts it seems Jack returned home to Tyneside, lining out for Wardley Welfare FC in his home town of Gateshead, and perhaps spending a bit more time with his family. His younger brother Bill, who had mirrored Jack’s career somewhat, joining Darlington and later Everton, without ever enjoying Jack’s success, was back playing his football in Gateshead as well, turning out for Gateshead FC in the Third Division North. Back in Dublin, Dolphin enjoyed one of their best ever seasons, winning the League title, the Dublin City Cup and finishing runners-up in the Shield without the suspended Jack O’Donnell. Ray Rogers finished as their top scorer, the former Bohemians man solving the centre-forward problem that had plagued them during Jack’s season with the club.

There was one final footballing adventure for Jack and it involved a return to the League of Ireland. With Dolphin beginning the following season as defending champions they once again came calling for the services of Jack O’Donnell, however his time with them was to be very brief. After just one game, a 4-3 defeat to Sligo Rovers he was released only to be signed a week later by another Dublin side, Reds United who were enjoying their sole League of Ireland season. As luck would have it his first, and only game, for Reds he came up against his old side Dolphin with the game ending in defeat for the League newcomers. Once again Jack was released after a single game.

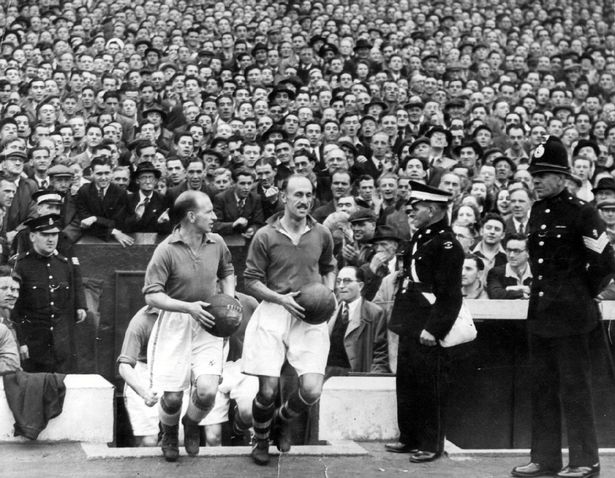

Be the end of the 1930s, his playing days behind him, Jack was back in the North East of England, living with his family and working as a labourer in a timber yard. He made a few more brief appearances in the sports pages – in 1948 when he visited the Everton team ahead of a game against Newcastle in St. James’s Park, while in 1952 he was listed as turning out in a charity match in South Shields alongside a number of other, well-known, retired players. It must have been one of the last games he played as he passed away later that year.

With special thanks to Rob Sawyer of the Everton FC Heritage Society for his assistance, especially the Topical Times article and photos of Jack O’Donnell while at Everton.