The whistle of Langenus

In the summer of 2018 as the elated French champions cavorted and the Croatian players lay prone and disconsolate a group of men in fluorescent light-blue jerseys went to the podium to collect their medals, they were referee Néstor Pitana and his team of officials. This was surely the sporting pinnacle for Pitana, who had celebrated his 43rd birthday just a month before and had begun his career refereeing in the Argentine second tier back in 2006.

But Néstor Pitana is but the latest link in a chain that stretches back almost 90 years to John Langenus, the Belgian official who had refereed the chaotic first World Cup final in 1930, as well as games in the 1934 and ’38 tournaments and the 1928 Olympics. Such was Langenus’s international reputation that he was in high demand for club games outside of his native Belgium, and it is here that the Irish connection appears, because just three months before he refereed in the Amsterdam Olympics of 1928 and two years before the World Cup final, he was in Dalymount Park for the Free State Cup Final between Bohemians and Drumcondra.

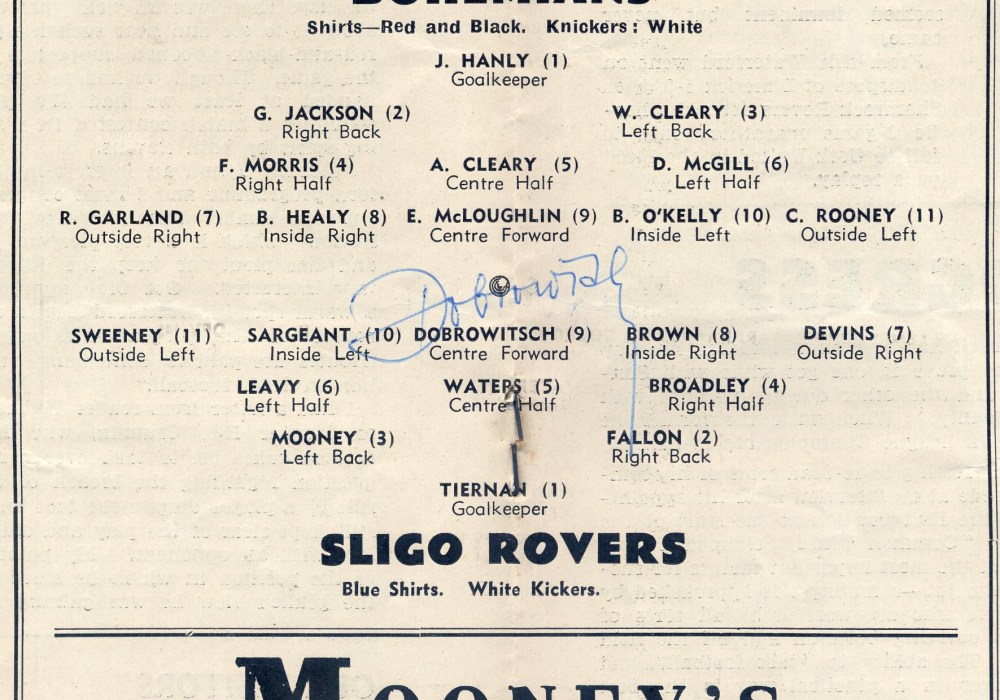

Bohs won that Cup final 2-1 in front of a crowd of over 25,000 on St. Patrick’s Day, 1928 to secure a clean sweep of all four domestic competitions that season. Their goals came from Jimmy White and Billy Dennis which cancelled out John Keogh’s opener for Drums. Match reports record that the Bohs were deserved winners with Drumcondra offering little in attack after their opening goal. Of the referee’s role The Irish Times noted that “while feelings ran high at intervals, the referee, Mr. Langenus of Belgium, handled the game splendidly and that nothing unseemly occurred to mar the enjoyment of the huge crowd”.

Langenus was something of a Pierluigi Collina of his day, well-known, popular and well-respected throughout the sporting world as well as being visually arresting, as a tall figure with slicked back hair who took to the field in a shirt, tie, jacket and a pair of plus-fours. It was this reputation that led him to Dalymount Park in 1928. Then as now there were constant debates about the quality of referees and plenty of criticism was aimed at the men in the middle during the early years of the League of Ireland. This meant that for high profile games such as Cup finals the FAI had established the practice of bringing in referees from outside of Ireland.

Usually this meant an English referee, Ireland still looked to England as a bastion of the game and it made sense to use an English speaking referee. For example, in 1927 J.T. Howcroft from Bolton had taken charge of his second FAI Cup Final. A prominent English referee, Howcroft had also officiated the 1920 FA Cup final between Aston Villa and Huddersfield. However, John Langenus had two things in his favour, he was a fluent English-speaker and in addition to his native Flemish he also spoke French, German, Spanish and Italian. The second reason that it should not be such a surprise that he refereed the Cup Final was that a year earlier he had been in Lansdowne Road to referee the Ireland v Italy international which Italy had won 2-1 thanks to two goals from Juventus striker Federico Munerati.

At a banquet following that Ireland match held in the Hibernian Hotel on Dawson Street where John Langenus and his wife were guests, the Honourary Secretary of the Association John S. Murphy toasted Langenus and described him as “one of the best referees they had ever seen in Dublin”. This surely helped with his appointment to the following year’s Cup final.

The paths of the Irish national team and John Langenus would cross on several further occasions, he took charge of Irish matches against Spain, the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland and finally against Czechoslovakia in 1938. Langenus himself had many happy memories of his trips to Dublin. He committed some of these to record in one of his memoirs Whistling through the world printed in 1942.

In his book he recalls witnessing the St. Patrick’s day parade on the morning of the FAI Cup Final, as well as his chats with Lord Mayor of Dublin Alfie Byrne, and his visits to the main tourist attractions; Dublin Zoo, the Botanic Gardens and St. Michan’s Church where he saw the famous preserved bodies in the church crypt. But his main memories are of Irish social culture, and Irish drink! John Langenus took a particular interest in Irish whiskey and would go directly to the distilleries to buy 90 and 100 year old bottles that wouldn’t usually be found on general sale, these he would keep as special gifts for friends (and perhaps a couple for his own collection). He was lucky on one occasion that he managed to bluff his was through English customs checks with two bottles of vintage whiskey in his suitcase.

Similarly he remembered the good humour of the after-match banquets, once again his beloved Irish whiskey makes an appearance though he mentioned that the only way he could tell his Irish hosts were getting a little drunk was that they tended to sing more. In winning or losing he recalls the good mood of his hosts remained the same.

Not all of Langenus’s sporting engagements were to be as enjoyable. His most famous role, that of World Cup Final referee was as far from the relaxed surroundings of a Dublin banquet as was possible. As the great Brian Glanville wrote of Langenus during that final match in Montevideo’s Estadio Centenario “The prospects of dealing with twenty-two players, each of whom was capable of disputing any and every decision, to say nothing of the nearly 100,000 spectators who, once they had paid their money, felt entitled to behave as they pleased, would have daunted men of lesser experience and courage than Langenus”.

Doubtless that Langenus was experienced and courageous but he was also pragmatic, he would no doubt have heard the chants and songs thousands of passionate Argentine fans as they streamed from their ferries across the River Plate and into the stadium hours before kick-off, he would have heard their Uruguayan counterparts fanatically chanting their own calls to arms, including the ominous “Victory or death!”. Who’s death exactly? In such cases often it’s the referee in the firing line and Langenus had sought assurances from the Montevideo police that a swift, armed escort, direct to their ship should be arranged right after the match for him and his team of officials should this be required.

Although the match was intense and undoubtedly passionate Langenus escaped the ire of either set of supporters, in fact he was involved in solving the biggest point of conflict even before kick-off. With both sides insisting that a football manufactured in their own country be used, Solomon-like, Langenus agreed that a ball from Argentina would be used in the first half and a ball from Uruguay in the second.

On that day, as Uruguay celebrated victory in the maiden World Cup, in front of their own home fans, John Langenus must have realised he had reached the apex of his refereeing career. He would return again to officiate in the next two World Cups, signing off his last World Cup match officiating the 3rd place play-off in 1938 which saw Brazil claim bronze, defeating Sweden 4-2. While he continued to referee international games for another year the outbreak of World War Two effectively ended his career as an international referee though he continued to referee matches in the Belgian League throughout the War until finally the league was suspended for the 1944-45 season. By that stage Langenus was 53 years of age.

According to one source, as a teenager he had played youth football for AS Anversoise but was already a referee in the Belgian top flight since at least 1912, refereeing his first international match in 1923 aged just 31. Throughout his career he was a committed amateur. He worked as a public servant in his home city of Antwerp for his whole working life and was also an occasional sports journalist. While on international duty only his expenses were paid and he refused any fees to referee games though often in such instances medals, cut glass, watches or decorative cups were given as mementos. He also had the perk of being able to bring back the likes of whiskey from Ireland or cigars from Spain. His positively Corinthian idealism is evident even just by looking at him with august bearing and almost formal attire.

His talent for writing was something that he put to good use in his retirement, writing a memoirs and two other football related books. He passed away in his native Belgium in 1952 aged 60.

With thanks to the people behind @WC1930blogger and @RefereeingBooks for their assistance.

As a young lad the sporting geography of the city was always fairly fixed and familiar to me. You saw Bohs and maybe the odd Cup final at Dalymount. You saw Ireland in Lansdowne Road, the Dubs in the freezing expanse of Parnell Park in the league, and if things were going well, in Croke Park in the sun. Morton Stadium in Santry was an annual pilgrimage for the National Athletics championships and as for Tolka Park, well that was Shels’ home, and to the unquestioning mind of a child it was always thus.

As a young lad the sporting geography of the city was always fairly fixed and familiar to me. You saw Bohs and maybe the odd Cup final at Dalymount. You saw Ireland in Lansdowne Road, the Dubs in the freezing expanse of Parnell Park in the league, and if things were going well, in Croke Park in the sun. Morton Stadium in Santry was an annual pilgrimage for the National Athletics championships and as for Tolka Park, well that was Shels’ home, and to the unquestioning mind of a child it was always thus.