Stuck in the middle – foreign referees in the League of Ireland

Controversy about refereeing decisions and the appointment of referees is nothing new in football. In the League of Ireland especially perceived biases, supposed club alliances, city of origin, and indeed refereeing ability all play into the arguements fans make about the unsuitability of a referee to take charge of a game. Of course their club of choice is uniquely victimised by Ireland’s officials while their rivals of course recieve favoured status – “sure doesn’t the ref support X team” or “doesn’t his young lad play for their under 15s” etc. etc.

This was a topic hotly discussed in the early days of the League of Ireland, with occassionally dramatic and even violent results and a pattern began whereby officiating Cup Finals and other high profile games became almost the exclusive preserve of referees from outside of Ireland. Bringing in referees (mostly from England) did help with tackling percieved bias that a referee might have held for or against any club and in many cases those taking charge were well known and respected in the game, even including men who had refereed World Cup and European Cup finals.

The first three FAI Cup finals were all refereed by Irish officials but by 1925 things had changed. Jack Howcroft of Bolton was brought in to take charge of the final due to be held on St. Patrick’s Day, 1925 in Dalymount Park. There was initial resistance to this from domestic referees, including the calling of strike action in the run-up to the Cup Final. Howcroft refused to break the strike but a Cup final without a referee was averted after the Evening Herald journalist William Stanbridge, who wrote under the sporting byline of “Nat” arranged a meeting between the disputing parties. Ultimately the referees association capitulated and recognised the FAI’s authority in appointing the referee for any competition and Howcroft was able to take his place as the man in the middle for the final between Shamrock Rovers and Shelbourne.

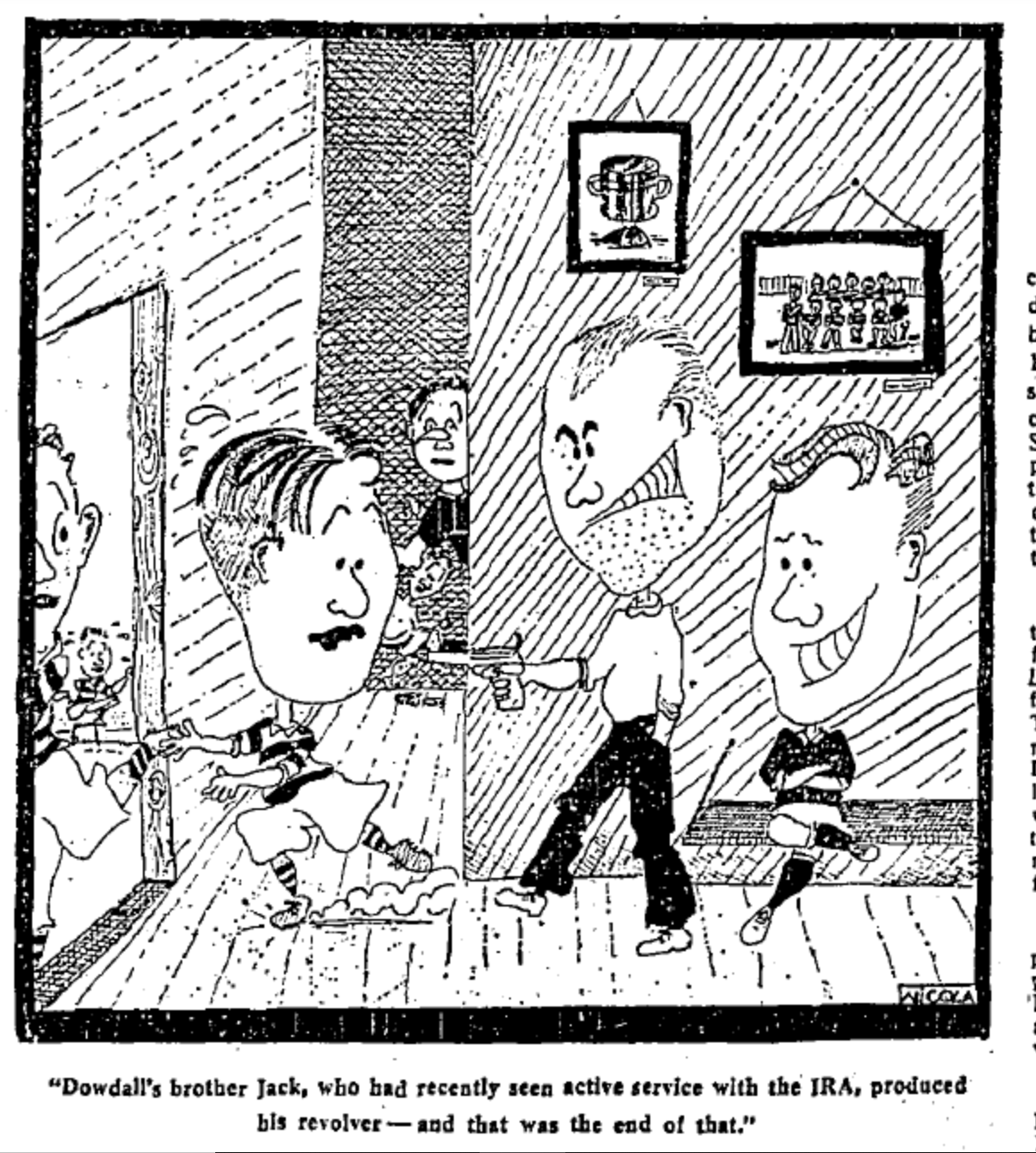

Howcroft was an experienced referee who had already taken charge of the 1920 FA Cup Final between Aston Villa and Huddersfield Town as well as 18 international matches by the time he made the journey to Dublin. He’d also taken charge of a match between Glentoran and Belfast Celtic some years earlier when he was greeted upon arrival by “a salute of umpteen revolvers” being fired in the air. Despite that experience Howcroft had no qualms about taking charge of the FAI Cup Final.

There was a record final crowd that day in Dalymount as attendance numbers breached 20,000 for the first time, and those present witnessed Shamrock Rovers 2-1 victory over their Ringsend rivals Shelbourne. Howcroft was well received and the crowd were in good spirits , despite, or perhaps because, the Government had just begun the practice of closing the pubs for St. Patrick’s Day. It wasn’t to be Howcroft’s last appearance at an FAI Cup final. Despite the fact that the FA, since 1902 had maintained the practice that a referee was to only be given the honour of refereeing a Cup final once, the FAI took a different approach and were happy to appoint referees to take charge of a final on multiple occasions.

Howcroft would return in 1927, while a year later his place in the middle was taken by Belgian referee John Langenus. Two years after taking charge of that Cup final clash between Bohemians and Drumcondra, Langenus was refereeing the first World Cup Final in Mondevideo. I’ve written about Langenus and his fascinating footballing journey, including his visits to Ireland elsewhere.

Non- Irish referees took charge of every subsequent final between 1925 and 1940 apart from the 1937 final which was refereed by John Baylor from Cork. Baylor was chosen ahead of English referee Isaac Caswell but this decision did not prove popular with everyone as finalists St. James’s Gate lodged a formal protest at his selection.

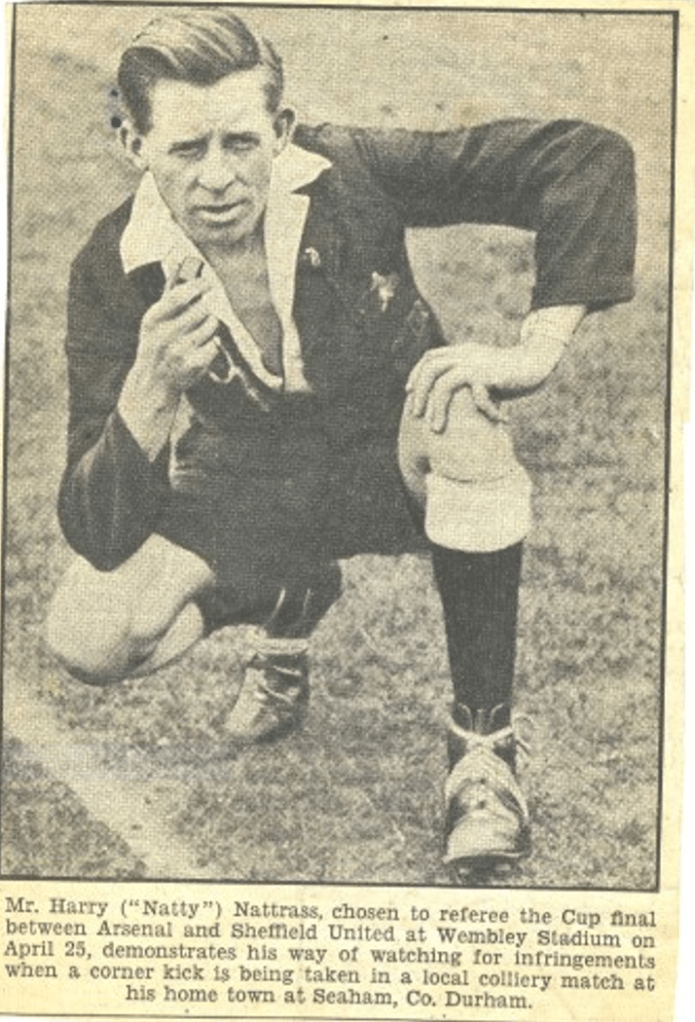

Harry Nattrass, from County Durham took change of the 1940 FAI Cup final between Shamrock Rovers and Sligo Rovers in front of a then record 38,000 supporters, Nattrass had refereed the FA Cup final just four years earlier, however despite his willingness to brave a crossing of the Irish Sea to take charge of the final in Dalymount the remaining finals during the War years would be the domain of Irish referees only. The escalation in the conflict and the danger to shipping from the German Kriegsmarine was obviously a major contributing factor, however, it is worth nothing that even after the War had ended it was 1950 before another non-Irish referee took charge of a Cup Final.

The 1950 final was in itself slightly unusual as it was the first final to go to a second replay. For the first two finals W.H.E. Evans of Liverpool took charge of the first two games between Transport and the favourites Cork Athletic, however he was replaced for the second replay by his fellow countryman Tom Seymour. Transport shocked Irish football by winning their first, and only Cup, and Tom Seymour would return the following year when Cork Athletic once again reach the final and eventually won on the replay 1-0 against Shelbourne.

The 1950s remained a decade when the FAI looked to England to provide referees for prominent games. This wasn’t confined to FAI Cup finals but also happened in semi-finals, prominent League of Ireland games, Shield games, Leinster Senior Cup games and more.

This was not always popular with all members of the public. In 1932 two English referees, shortly after arriving in Dublin, were “requested” not to officiate two games involving Shelbourne over two consecutive weeks. First, Tom Crew of Leicester was visited ahead of a Shels games against Cork and the following week Tommy Thompson from Lemington was visited before a game against Drumcondra. Both referees did take charge of each of the games although Thompson did alert the Free State League committee. The League condemned these visits to referees and committee member Basil Mainey of Shamrock Rovers stated that the “attempts at intimidation were made by irresponsible persons.” The Gardaí, League and the FAI were reported to be investigating the matter by the Irish Press. Mainey did comment further, making a somewhat awkward justification for the use of English officials while also giving an idea of the rates of pay being offered in the early 1930s. He said;

“No one should get the idea that we employ English referees for the love of them or their country. It costs us four of five guineas every time and a local man would only cost about one guinea.”

The League committee stated at the time that with bigger games in the League of Ireland regularly attracting over 20,000 spectators that it was “desirable” that a “stranger acted as referee”, again returning to the idea that an English referee would be seen as impartial and unbiased. Not that there weren’t moments of friction, three years before those visits were paid to referees Crew and Thompson there was a spat between referee Albert Fogg and Dundalk FC over an article he had written in the English sporting press describing a league match he had refereed between Dundalk and Drumcondra. Fogg had described the Dundalk crowd as the “wild Irish” and a complaint was made by PJ Casey on behalf of Dundalk FC. Incidentally, Irish referee JJ Kelly wrote to the FAI in support of Fogg and complained that the Dundalk supporters were “the mostly cowardly lot of blackguards that ever attended a football game”.

Fogg was well used to taking charge of games in Ireland, he had refereed the 1926 FAI Cup final and was another man afforded the dual honour of taking charge of Cup Finals in both England and Ireland when he refereed the 1935 FA Cup final. As with Fogg, Langenus and Howcroft the majority of referees who came to Ireland were quite high profile, many refereed international matches and important league games and Cup Finals in England, and in the case of Langenus even the World Cup final. Among the other well-known refs who came to Ireland during this period from the 1920s through to the early 1960s were men like Albert Prince-Cox a former football manager, player and referee, boxer, and boxing promoter who had also designed Bristol Rovers distinctive blue and white quartered kit.

Perhaps the most well-known figure in this period would be Arthur Ellis. Ellis was in charge of the 1953 FAI Cup Final and its replay and also the 1955 FAI Cup Final. By that stage he had already been a linesman in the Maracanã for the 1950 World Cup final, and would referee at both the 1954 and 1958 tournaments. A year after refereeing Shamrock Rovers victory over Drumcondra in 1955, Ellis was entrusted with refereeing the first ever European Cup final, a classic game which was won in thrilling fashion 4-3 as Real Madrid defeated French side Stade de Reims. One of Ellis’s assistants in that European Cup final was Thomas H. Cooper who would referee another Shamrock Rovers v Drumcondra final in 1957, this time the Drums prevailed. Ellis himself became better known to a later generation as a media personality, being the referee in the TV gameshow It’s a Knockout.

As you can see from several examples above the FAI did not follow the English tradition of a referee only getting to take charge of a Cup Final once, Howcroft, Seymour, and Ellis all refereed two FAI Cup finals, although the record for a foreign referee is three, which is held by Isaac Caswell from Blackburn. Caswell was a Labour Councillor and was also very involved in organising (and delivering) Church services for sportsmen. He was the man in the middle for the 1932, 1934 and 1936 FAI Cup finals. It could have perhaps even been more were it not for the fact that Argentina were experiencing a similar situation to the League of Ireland and wanted British referees to take charge of league games there while also instructing and education local referees.

Caswell journeyed to Argentina in late 1937 and stayed until 1940, refereeing matches and training local officials. Caswell seems to have been popular in Argentina and like Ireland was seen as an impartial adjudicator although as with games in Ireland there were still moments of conflict. In 1938 there were reports that Caswell had been assualted during one game, although broadly speaking it was seen that his time there was a success. So much so that in the late 1940s there was a request for more British officials to take charge of fixtures in Argentina. Eight men departed for Argentina in 1948 with allowances made for their wives and children to travel with them

This group weren’t always as popular as Caswell had been and similar to the 1925 incident with James Howcroft there was a threatened strike by the Argentine match officials in 1950 while there were still some tumultuous scenes on occasion, with referee John Meade and his officials having to barricade themselves inside a dressing room during a game between Huracán and Velez Sarsfield.

In both Ireland and Argentina the use of referees from outside of their own Associations gradually came to an end. The last Englishman to referee an FAI Cup final was D.A. Corbett who took charge of Shamrock Rovers v Cork Celtic and the subsequent replay in 1964. Since that time the FAI Cup has been the preserve of Irish referees, however for a span of almost forty years British referees (and one Belgian) took charge of 26 FAI Cup finals as well as innumerable semi-finals, finals of other Cup competitions and prominent League and Shield games. Many of these referees had a reasonably high profile, took charge of international matches and tournaments, European club ties and English top flight games and FA Cup Finals, and while not always welcomed they were broadly viewed as neutral parties, freeing games of any sense of bias and bringing their expertise in the laws of the game to bear.

A special thank you to Dr. Alexander Jackson of the National Football Museum in Manchester for his assistance.