We’ve only begun the year of commemorations and there has already been a great deal written about the various organisations, groupings and competing actors around the dramatic events of Easter 1916. In much of nationalist history there is a huge role played by sport in the recruitment and training of the Volunteers, this is something often celebrated by the GAA and is born testament to in the naming of stadiums and club teams around the county.

This involvement with the nationalist cause was not limited only to the sphere of Gaelic games. Despite its occasional portrayal as a “Garrison Game” many individuals who were actively involved with football clubs also became key players in the struggle for independence. Among them were family members of my own.

In doing some family tree research I’ve started looking into the history and background of some of the relatives on my Da’s side of the family, people I was vaguely aware of but who by and large had died before I was born. This trail has brought me to a few individuals, my great-grandfather Thomas Kieran (occasionally spelled Kiernan) his sister Brigid and her husband , my great-uncle, Peadar Halpin.

At this point I must state that I do indeed have some non-Dublin blood in my veins, not much mind, but both Thomas and Peadar were from Co. Louth. Peadar would come to prominence due to his association with Dundalk FC and the FAI. He was a founder member of the club and spent decades on the management committee of Dundalk FC and was also club President. He also served as Chairman of the FAI’s international affairs committee and President of the League of Ireland and also Chairman of the FAI Council.

Football in Dundalk, in a somewhat disorganised fashion could be found as far back as the late 19th Century and some of the impetus given to the game in the early 20th Century can be traced back to a Dundalk architect named Vincent J. O’Connell. He had played for scratch teams in the town in his youth and had been a member of Bohemian FC between 1902 and 1907 during a sojourn in Dublin. Upon his return north he set about working with others to bring some structure to the playing of the association game in the town. The club we know today as Dundalk FC began life as Dundalk GNR, the GNR standing for Great Northern Railway, and they spent a number of years in junior football before being elected to the League of Ireland in the 1926-27 season. The campaign for election to the league as well as the eventual re-branding of the club to Dundalk FC was apparently the result of the machinations of a group of local football enthusiasts comprised of Peadar Halpin, Paddy McCarthy, Jack Logan, Paddy Markey and Gerry Hannon. According to a report in the Irish Times the decision to change the club’s colours from black and amber to white and black was made by one Barney O’Hanlon-Kennedy who promised his silver watch as a raffle prize for a fundraiser for the club. As he was the one putting forward the funds he was given the honour of selecting the team’s colours.

That Dundalk should be so connected with the railway shouldn’t be that surprising, then as now, Dundalk was a major station between Dublin and Belfast, even if the creation of the border did cause disruption. My great-grandfather Thomas Kieran (born in 1889, son of Patrick and Annie Kieran) was a worker for the railway, at the time of the 1911 census when he was 22 years old and residing in the family home of 14 Vincent Avenue in Dundalk (five minutes from the train station). He was listed as being an “engine fitter”, while his father Patrick was a carpenter for the railway as well. Later reports show that Patrick was also involved with the union (the Irish Vehicle builders and Woodworkers Union) and was among the workers representatives when a strike was threatened in 1932. The census also reveals that of the family of five both Thomas and his sister Brigid spoke Irish.

House in Vincent Avenue today, they were build c.1880

Republican roots, what the records say…

When searching through the Bureau of Military history records I came across a number of references to the Kieran family. One referred to the family as a “Volunteer family….railway people”. This came from the witness statement of Muriel MacSwiney, the wife of future TD and Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney who stayed with the Kieran family during one of Terence’s frequent bouts of imprisonment. This is confirmed by the witness statement of another local Volunteer James McGuill who referred directly to Brigid saying that Muriel MacSwiney “stayed in Dundalk with Miss Kieran now Mrs. Peadar Halpin.”

Muriel MacSwiney

On a slight digression Muriel MacSwiney was a fascinating woman, born Muriel Murphy, her family owned the Midleton Distillery and they were firmly against her marriage to Terence MacSwiney and even tried to get the Bishop of Cork to intervene to delay it. As a footnote that will become relevant later, the best man at their wedding was Richard Mulcahy the future Chief of Staff of the IRA, Minister for Defence during the Civil War and later still, leader of Fine Gael. Terence was in and out of various gaols during the course of his short marriage with Muriel, he would be dead by 1920 at the age of just 41, wasting away on hunger strike in Brixton Jail. The impact his death had on the wider world is probably comparable to that of Bobby Sands six decades later. MacSwiney was viewed by many as a martyr in a fight against Imperialism and was cited as an influence by Mahatma Gandhi as well as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

Apart from providing lodgings for Muriel MacSwiney it’s worth looking at what else the Halpins and Kieran’s were up to at this turbulent time. Thomas Kieran is mentioned again the the Bureau of Military History. In the witness statement of Patrick McHugh, Operational Commander and Lieutenant of the Irish Volunteers in Dundalk during Easter week 1916 listed Thomas Kieran among those “who served Easter Sunday 23rd April 1916, remained with company that day and, volunteered to return home when uncertainty of position was explained to them. Some returning Sunday night, others Monday morning or as Stated.” Interestingly Thomas is already listed as living in Dublin by this stage while most of those mentioned were still living in Dundalk. Peter Kieran (a possible relation?) another Dundalk based Volunteer declared in his witness statement that Thomas Kieran was among a group of Volunteers who had arranged to meet on the night of Thursday 20th April with plans to make their way to Dublin to join the rest of the Volunteers in the Rising. They had elaborate plans to get there via motor boat but were warned that the Royal Navy had vessels patrolling the area.

The plans for the Thursday journey to Dublin was called off and the group met again on Friday and Saturday night, however word came that the Rising was off, probably a reference to Eoin MacNeill’s order cancelling the Rising, which obviously had a significant impact on the numbers of those who arrived in Dublin. Peter Kieran went on to state that about the second week in May arrests were made in the town by the RIC. The family version of the story that I’ve been told was that Thomas was one of those arrested while cycling his bike with a rifle on his back and that he was later interned!

Peter Kieran in his statement also noted that “Those who served 23rd, 24th and 25th April 1916 and became disconnected, were ordered home on account of age, infirmity or as stated. [included] Peter Halpenny or Halpin [of] Byrnes Row Dundalk” Although it is hard to be absolutely certain this Peter Halpin could well be our Peadar Halpin, he was listed as Peter on the earlier census return. There is also a record of a P. Halpin from Byrne’s Row who was arrested a couple of weeks after the Rising and sent to Stafford Detention Barracks in England on 8 May 1916. There are other references in other sources to a P. Halpin of Byrne’s/Burn’s Row being arrested and sent to Stafford.

In searching the medal rolls for this issued the 1917-21 Service Medal both Peadar and Brigid appear. Both were issued the medal, Brigid in 1943 and Peadar in 1951. Her deposition states that Brigid was a member of Cumann na mBan from before the Rising. She was involved in dispatch work, fundraising for the purchase of arms, did election work for local candidates and visited republican prisoners. Peadar in his deposition states he was a member of “A” company of the 4th Northern Division of the IRA and that his involvement also predated the Rising, going back to 1915. It doesn’t however, detail individual operations of which he was part.

Patrick McHugh (who we encountered above) managed to escape arrest although he was interrogated by RIC men just after the Rising. He then moved up to Dublin to stay with his sister on Iona Road for a short time until he “got in touch with friends Tom Kieran and his wife [the granny Kiernan], who had a room in Mountjoy Street.” It seems that Thomas Kieran had moved to Dublin sometime between 1911 and 1916. I know he ended up working in the CIE engineering works in Inchicore for many more years. He obviously met Jane Brennan (2 years his junior) when he moved to Dublin, she had been living on Dominick Street Upper at the time.

The house at 27 Blessington Street, just off Mountjoy Street, where the Kierans lived.

Peadar was born in 1895 and grew up in Stockwell Lane, Drogheda. He trained as a cooper, (the trade of his father John) before moving to Dundalk to work in the Macardle Moore Brewery where he later became the foreman cooper. It is interesting to note that his wife Brigid was 12 years his senior. He came from something of a Republican family and a street (Halpin Terrace) in Drogheda bears the family name. This street has something of a tragic history to it as it was named after Peadar’s younger brother Thomas, who was killed there by the Black and Tans in February 1921. At the time Thomas was an Alderman of the local Corporation representing the Sinn Féin party. Thomas Halpin, along with another man, John Moran were abducted from their homes and brought to the local West Gate barracks where they were brutally beaten. They were then dragged to a third man`s home, that of a Thomas Grogan whose house was also raided but fortunately Grogan had been tipped off and had made his escape before the Tans arrival. It was at this spot that Thomas Halpin and John Moran were murdered, their bloodied bodies being discovered there the following morning. Each year the local Council commemorates this event and a monument now stands at the site of the men’s murder.

Commemorations for Alderman Thomas Halpin & Captain John Moran in 2014

Footballing connections; all roads lead to Bohs

Thomas, is something of a family name, Peader’s brother Thomas was tragically killed and Peadar would name a son of his as Thomas, perhaps in tribute to his murdered sibling. Thomas Kieran would also have a son named Thomas and there is an interesting football overlap as both of these men named Thomas would have a part to play in the history of Bohemian FC.

Peadar’s son Tom lined out for Dundalk in the early 40s before moving to Bohemians in 1947. He featured prominently in Bohs run to that season’s FAI Cup Final where he was part of a team that defeated Drumcondra FC, Shelbourne in the semi-final (where Halpin scored a penalty) and took on a highly talented Cork United side in the final. Cork United had been the dominant team of the 1940s and had already won five league titles by the time they took on Bohemians in front of over 20,000 fans at Dalymount Park on April 20th 1947. The Leesiders were the strong favourites. Bohs were at an added disadvantage as two of their key, experienced defenders (Snell and Richardson) were out injured. Halpin was playing at right half and spent most of his time trying to counteract the attacking threat of Cork’s forward line which included Irish internationals like Tommy Moroney and Owen Madden.

The Bohemian team from the 1947 final

Bohs were already 2-0 down before 30 minutes were on the clock but Mick O’Flanagan managed to pull one back before Halpin scored a penalty after Frank Morris was fouled in the box. The game finished 2-2 and went to a replay four days later. In a howling gale and lashing rain Bohs lost out in the replay in front of barely 5,500 people with the Munstermen winning 2-0.

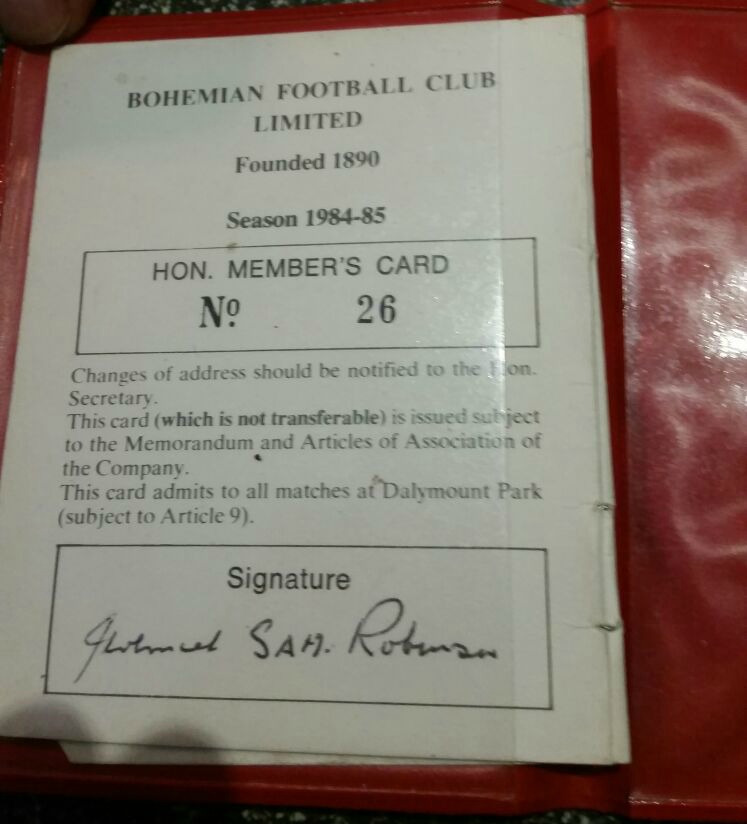

Tom Kieran’s connection with Bohemians was a very long one, a referee for decades, including at League of Ireland level in the 1960s. The uncle Tom was a member of Bohemians since 1969 and was Vice-President of the club from 1985 to 2000 and was later made an Honorary Vice-President for life. Tom’s daughter Susan and her husband Dominic are of course still very familiar faces down at Dalymount to this day.

The uncle Tom as photographed for an Evening Herald profile in Dalymount Park

There are further remarkable connections with the Halpin family and with Dundalk and Bohemians as Thomas Halpin’s grandson; Peter was the Commercial Manager at both Dundalk FC and Bohemian FC as well as having a spell with Belfast club Glentoran.

Despite these many connections with the beautiful game the strongest and most influential roles in Irish football were undoubtedly held by Peadar Halpin. He was on the committee of Dundalk FC since at least 1926 and had two spells as Club Chairman from 1928-1941 and 1951-1965 and in 1966 he was appointed Club President, a position he was re-elected to in 1973. He also held a number of roles for the FAI, he was Chairman from 1956-1958 and had many years previous experience on various FAI committees and had made an unsuccessful attempt at arranging UEFA mediation to help resolve the long-running schism between the FAI and the IFA. At the age of 70 he was elected as President of the League of Ireland, it was a role he hadn’t been expecting to fill but after the Dundalk rep Joe McGrath became ill Peadar was the only member of the Dundalk committee with sufficient experience to take on the role. While the FAI and League of Ireland have (with good reason) been seen as conservative and at times backward there were a number of advances that took place during his tenure. It was the Dundalk committee that suggested the introduction of the B division which would eventually lead to the creation of the First Division as well as overseeing the admittance of new clubs to the League of Ireland. On a local level he was crucially involved with the development of Dundalk FC as a force within the League of Ireland, at present they are the second most successful side in Irish club football with 11 League titles and 10 FAI Cups. He claimed that of the many successful years that Dundalk enjoyed his favourite was 1942 when Dundalk beat Cork United 3-1 in the FAI Cup final and Shamrock Rovers 1-0 in the Inter City Cup.

Mattie Clarke in action for Dundalk in the 1950s as featured in the Irish Times

A potential politician?

Despite this extremely long connection with Dundalk FC the earliest reference to his involvement was in 1926. Prior to that we know that he was working as a foreman cooper in the Macardle Moore Brewery but in March 1923 his name appears in a debate in Dáil Éireann when his local TD Cathal O’Shannon raised a question on his behalf with the then Minister for Defence, General Richard Mulcahy. This is the same Richard Mulcahy who had performed best man duties at the wedding of Terence MacSwiney and Muriel Murphy who the Halpin’s would later shelter. It is testament to the divisiveness of the Civil War that such former allies could be so opposed.

O’Shannon had been elected TD for Louth-Meath in 1922 as a member of the Labour Party and was a supporter of the Treaty of 1921 which had officially led to the partition of Ireland. Mulcahy as Minster for Defence was a highly controversial figure for some as it was he who gave the order for 77 executions during the Civil War. The content of O’Shannon’s query was a request for an update on the status of Peadar Halpin and the likelihood of his release from Newbridge Barracks where he had been held since August 1922. Mulcahy replied that “Mr. Halpin was arrested for aiding and abetting Irregulars during the time of their occupation of Dundalk. It is not considered advisable to release him at present”, he further added that Peadar was not to be allowed send or receive letters.

As for what “aiding and abetting the Irregulars” referred to, the most likely answer given the fact that Peadar was arrested in August 1922 in Dundalk was that he was involved in assisting the anti-Treaty IRA (or “Irregulars”) in their attack on Dundalk on August 16th 1922. During this attack, led by future Tánaiste Frank Aiken, the anti- Treaty forces captured the town, freed over 200 prisoners held in the barracks and also took over 400 rifles. Rather than try to hold their position the town was re-taken the following day by Free State forces. In all the attack on Dundalk cost the lives of six Free State soldiers and one officer as well as the lives of two of the “Irregulars”. It is not clear what assistance Peadar provided during this time but it was obviously significant enough to warrant him being held in gaol for months without charge.

Family recollections of Jane Kieran née Brennan, the wife of Thomas Kieran are fairly clear on her views on Mulcahy and Cumann na nGaedheal, she put it bluntly and succinctly, saying “they cut the old age pension and they shot them in pairs”. It was not to be the last connection between Peadar and Cathal O’Shannon or Frank Aiken for that matter as the below excerpt shows.

From the Irish Times April 29th 1927

Cathal O’Shannon stood in the new Meath constituency in the first general election of 1927 and in his absence as the Labour candidate it was proposed that Peadar should run. Among his competition would have been the man he likely assisted during the Civil War, Frank Aiken. However as is the cross that left-wing politics must bear, there was a split, those who proposed Peadar as a candidate were not successful in securing his nomination and Thomas O’Hanlon and Michael Connor ran, unsuccessfully, for the Labour Party. As another of my many side notes, Cathal O’Shannon was unsuccessful in gaining election in 1927 however he later became the first Secretary of the Congress of Irish Unions in 1945, the last president of this Congress was one Terence Farrell, head of the Irish Bookbinders and Allied Trades Union. His nephew Gerard, after whom I’m named, married Nancy Kieran which brings together the Farrell and Kieran clans. Their eldest son was my Da, Leo and as many in the family will know he played for Bohs in the early 60s.

Anyone who has read this blog regularly will know that I often try to look at life and history through the prism of football. Of particular interest is the role that “soccer men” played in the Rising and subsequent War of Independence and Civil War. This is probably the most personal post as I’ve tried to do the same with my own family and their involvement with the nationalist movement. There are many stories that I would love to include but haven’t but would appreciate any feedback or additional information from family members. I hope that this could be the first in a series of posts that might be of interest or maybe just a first draft of something more extensive, there were certainly enough stories told at uncle Joe’s funeral to fill a book, but I hope this might be a start.

With a special thanks to Jim Murphy, Dundalk FC historian for his assistance with some of the research for this piece.