The Dawning of the cup

Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock debuted on the Abbey Theatre stage in 1924 with the focus of the drama set in the city of Dublin after the outbreak of the Civil War just a couple of years earlier in 1922. The “Paycock” of the title, the feckless Captain Jack Doyle, became identified by the malapropism which he exclaimed repeatedly through the play, “the whole world is in a terrible state o’ chassis”. And indeed it was. If we take it that Captain Jack meant by “chassis” that the world was in a state of chaos and change then certainly his final drunken quip was accurate. Maybe he’d been at the first ever Free State cup final a few months earlier?

By the dawn of 1922 the truce in bloody War of Independence was’t yet six months old, the Anglo-Irish Treaty had only been signed in December of 1921 which allowed for the creation of a 26 county Free State by the end of 1922. But before that would happen 1922 would also witness the beginnings of the Irish Civil War. A state of chassis indeed.

In the middle of this chaos the Football Association of Ireland had been formed after a split from the Belfast-based IFA and a brand new league and cup competition were begun before the Irish Free State had even officially come into being. While that first season can be viewed as a success from a footballing perspective, it was not to be without incident or drama. Befittingly, it was the cup final that witnessed some of the most dramatic scenes.

The first season of the league had kicked off in September 1921, it only featured eight teams in total and all of them were from Dublin. Of those eight only two are still involved in League of Ireland football today, Shelbourne and Bohemians. The cup however, was slightly more diverse, featuring the likes of Athlone Town, who would join the league the following season, as well as West Ham. The West Ham from Belfast that is.

West Ham were a team in the Falls and District League in Belfast. When the split from the IFA occurred these clubs chose to affiliate with the FAI and in West Ham’s case their new cup competition. This wasn’t to be the only occasion that something like this happened, the following season the cup winners were Alton United, previously a junior club in Belfast they shocked Shelbourne in the final with a 1-0 win. The relative success of junior clubs from Belfast was likely to have drawn some condescending looks from the IFA in relation to the standard of football south of the border. But it should be noted that at the time due to the political turmoil in Belfast one the foremost clubs on the island; Belfast Celtic had withdrawn from the league and many of their players were active for sides in the FAI affiliated Falls and District league.

This would change when by the end of 1923 the FAI was admitted to FIFA. One of the conditions of acceptance being that only clubs from the 26-county Free State could be members of the Association. This meant an end to the involvement of northern clubs until Derry City joined the league in 1985. West Ham were not to have much of a cup run. Their highlight was holding Shelbourne to a scoreless draw before they were knocked out in a replay.

While the West Ham versus Shelbourne game may have been tight there were a few hammerings in the early rounds of the cup. In the opening round Dublin United beat their league rivals Frankfort 8-1. While Dublin United would drift out of football over the following few years Frankfort, from the Raheny area of Dublin are still active locally, playing their matches in St. Anne’s Park.

Despite their convincing win in the opening round Dublin United were dumped out in the following tie by Shamrock Rovers, then a Leinster Senior League side. Rovers had already had a long cup campaign before the met Dublin United. Not being a league club they had to negotiate a number of qualifying rounds which had their own fair share of drama. A comfortable win over UCD was followed by a trip to Tipp to take on Tipperary Wanderers. Despite the recent prominence of Shane Long we don’t often think of Tipperary as a soccer stronghold but the local side were good enough to beat Rovers 1-0. The men from Ringsend however, made a formal protest because of the poor quality of the pitch that they were forced to play on. A ruling was made that the match had to be replayed and this time Rovers emerged victorious.

Further victories followed over St. James’s Gates “B” side and Shelbourne United (a club who also had their origins in Ringsend but not to be confused with Shelbourne F.C.) which meant that Rovers were through to the first round proper of the cup against Free State league side Olympia. A 3-1 win there and the 5-1 hammering of Dublin United saw them drawn in the semi-finals against Bohemians.

Bohs being the more well established side went into the games as favourites. They enjoyed home advantage as both semi-finals were to be played in Dalymount Park, they’d finished a close second to St. James’s Gate in the inaugural league season and they’d demolished Athlone Town 7-1 in the previous round. But it was Rovers who emerged victorious thanks to a lone strike by John Joe Flood. The result was somewhat of a shock, accounts at the time describe Bohs enjoying the better of the play but failing to take their chances, ultimately the more direct, physical approach taken by Rovers paid dividends.

The scorer of the winning goal, John Joe Flood was one of the team’s early stars. A Ringsend local, he was the son of John Flood, a bottle blower at the nearby glass bottle works. He had previously played for Shelbourne but was very much a Shamrock Rovers man. He even spent some of his youth living on Shamrock Terrace, the road that gave Rovers their name. In all he had four spells at the club, while also trying his luck on two occasions in England, a short spell with Leeds United and later sojourn at Crystal Palace.

He was known as tough and pacey inside forward and was occasionally referred to by the nickname “Slasher” which makes him sound like a fairly formidable opponent. In Rovers’ colours he’d end up collecting four League of Ireland medals and six cup winners medals and later became part of the famous “Four F’s” forward line along with Billy “Juicy” Farrell, Jack “Kruger” Fagan and Bob Fullam. He would also be capped five times by Ireland, scoring four goals, including a hat-trick in a 4-0 victory over Belgium.

Victory over Bohs had secured Rovers’ place in the final, due to take place on St. Patrick’s Day 1922 but they would have to wait a while before the identity of their opponents was confirmed. The other semi-final had gone to a replay, St. James’s Gate versus Shelbourne had finished scoreless in their first meeting and there was a gap of more than two weeks before the game was replayed. The victors on that day were St. James’s Gate and they were confirmed as the side to face Rovers in the final on St. Patrick’s Day.

St. James’s Gate at the time were based around grounds in Dolphin’s Barn that were rented by the Guinness brewery which gave them their name. Guinness were known for the paternalistic attitude they took towards their workers and a job at the brewery offered a level of security and benefits that were not often found in other workplaces around Dublin. The James’s Gate players were nominally amateurs, five players from the team would be part of the amateur squad that competed for Ireland in the football tournament at the 1924 Olympics, but even by the time of the Cup final there were a quota of non-Guinness players allowed play for the team.

Some of those who weren’t Guinness employees included Ernie MacKay, the son of a Scottish soldier, Ernie worked for at the GPO for decades while also remaining involved with James’s Gate as a player and administrator well into the 1940’s. His team-mate at inside-left was Charlie Dowdall who had worked for Guinness briefly but spent most of his career working at the Inchicore railway works. Still they would have had access to the superior sporting facilities of the Guinness workers, pitches, gymnasiums and medical experts. Such was the prestige of the club at the time that many star players who did work at the brewery were excused from more taxing work to make sure they were fit and healthy for upcoming matches.

This approach had brought impressive results. In the 1919-20 season St. James’s Gate had won the Leinster Senior Cup, the Leinster Senior League, the Metropolitan Cup and the Irish Intermediate Cup. By the time the cup final rolled around on St. Patrick’s Day 1922 the Gate had already become the inaugural Free State league champions and Leinster Senior Cup winners, an FAI Cup win would seal a treble.

The Gate were favourites, despite the fact that they were technically viewed as an amateur “works” team whereas Rovers (still a Leinster Senior League side) were paying players between 20-30 shillings a game. The Gate possessed the league’s top scorer, Jack Kelly in their ranks, and while Rovers had a certain reputation for toughness and aggression (especially men like Bob Fullam, Dinny Doyle and William “Sacky” Glen) St. James’s were no push-overs in this regard.

Their midfield half-back line of Frank Heaney, Ernie MacKay and Bob Carter were tough, tall, physically imposing men. Heaney, a veteran at this stage, had won amateur caps for the IFA, while MacKay, Dowdall and the versatile Paddy “Dirty” Duncan would also all represent Ireland at the 1924 Olympics. They were certainly a side with pedigree.

What was described as a “fine holiday crowd” numbering up to 15,000 were in attendance in Dalymount Park that St. Patrick’s Day for the final. Despite the fact that the Gate midfield was physically bigger the Rovers half-backs were dominant in the opening half, but their forward-line, though “aggressive” missed a succession of chances and five minutes before the break Jack Kelly rose highest to power home a header from a Johnny Gargan corner kick to give St. James’s Gate a half-time lead.

Ten minutes into the second half Rovers restored parity, Paddy Coleman, the Gate keeper failing to clear a ball from an in-swinging corner meant an easy finish for the Rovers winger Charlie Campbell. Rovers rallied and had some good chances before the end of the game but their earlier slack finishing persisted and they failed to make their pressure count. The Irish Times used the standard parlance (then, as now) referring to the match as a “typical cup tie”, it was hard fought, but they complained that much of the play was “crude”. A replay was set of the 8th of April and there was even greater drama to come.

The crowd wasn’t quite as sizable for the replayed game, perhaps due to the fact that the Irish Rugby team were playing France that same day in Lansdowne Road and enjoying a rare will over Les Blues. The 10,000 or so who were there in Dalymount Park were in full voice, and the Gate’s Charlie Dowdall later described the atmosphere as “electric”, and remembered the “intense fanaticism between the supporters” before ominously noting that “those were the troubled days, and there were a few guns lying around in supporters’ pockets, though it all ended happily”. As we’ll see later at least one supporters’ gun didn’t end up staying in his pocket!

As the game kicked off with Rovers captain Bob Fullam winning the toss and deciding to play into the wind in the opening half, this didn’t seem to hamper Rovers who had the better of the play and created most of the chances, however, as in the previous game, they couldn’t make possession and territorial advantage count. Rovers errant finishing would cost them as a minute before the interval Johnny Gargan nicked the ball from Joe “Buller” Byrne (later a groundsman at Milltown) and squared for Jack Kelly who beat Bill Nagle in the Rovers goal with a fierce, low strike. Despite Rovers continuing to have the better of the play in the second half it would remain the only goal of the game as Paddy Coleman put in a display described as “miraculous” between the sticks for the James’s Gate.

The final whistle was met with a pitch invasion from some of the Rovers support who headed straight for the James’s Gate players. They were soon joined by several of the Rovers players. Two tough teams had obviously gotten under each others skin and Dowdall and Fullam in particular had been having something of a running battle throughout the match.

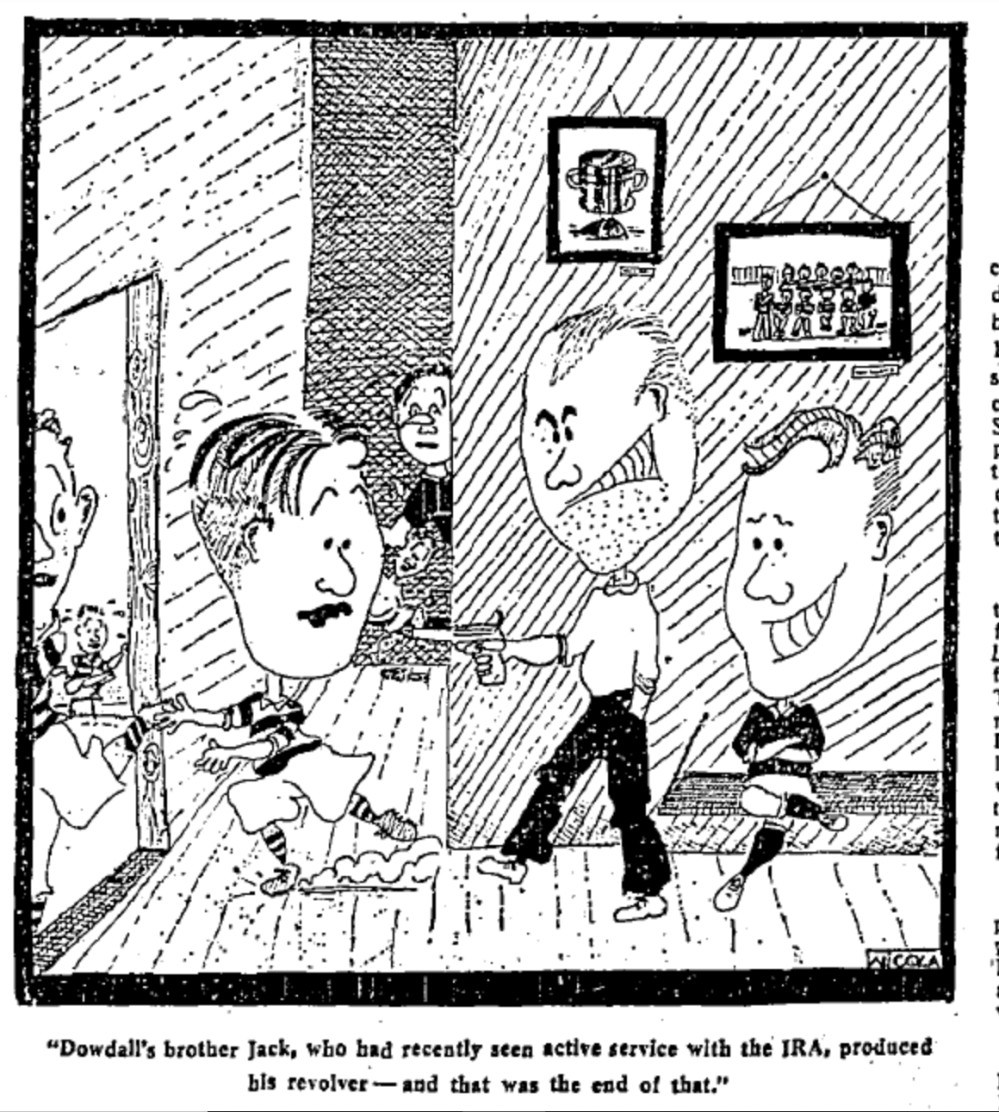

As the St. James’s Gate players made for the dressing rooms at pace they were chased from the pitch by the invading fans and three Rovers players. Bob Fullam, allegedly joined by Dinny Doyle and John Joe Flood, pursued the Gate players inside where Fullam advanced on the object of his ire, Charlie Dowdall. It all seemed set to kick-off when Jack Dowdall, Charlie’s younger brother and an IRA volunteer stepped forward and produced a pistol. Fullam and his Rovers teammates were outnumbered, and now out-gunned and they sensibly beat a retreat from the changing rooms. Fullam, along with Doyle and Flood ended up receiving bans from the FAI for their part in the disturbances.

Fullam wouldn’t be banned for long and ended up scoring 27 times in the league for Rovers the following year. Most with his howitzer-like left foot. While his first cup final may have ended is defeat he would retire from the game with four winners medals to his credit, to go with the four league titles he’d collected. So central did he become to Rovers success that the popular refrain among their support whenever the team were lacking inspiration on the pitch was “Give it to Bob”, a phrase that entered widespread use through Dublin in the subsequent decades.

Fullam also has an important footnote in Irish international football history. After the 1924 Olympics few international matches were forthcoming and the FAI had to wait until 1926 to secure a full international fixture, in this case a game against Italy in Turin with a return game in Dublin also agreed. Fullam and Frank Brady of Fordsons were the only players to play in both of those early games. The Italians ran out comfortable 3-0 winners in Turin but performed better in Lansdowne Road the following year with Ireland taking the lead through a powerful strike from none other than Bob Fullam. It was counted as the first goal in International football for a FAI national team. Indeed he nearly grabbed a second shortly after from a free-kick, the power of which meant that Mario Zanelli, the Italian full-back was stretchered off after he blocked the fierce shot with his head. Despite the performance that was to be Fullam’s last cap for Ireland, he was by then into his 30’s and Rovers were to be the main focus of his footballing exploits.

That inaugural season of Free State football belonged to St. James’s Gate who finished with three trophies, while Paddy Duncan, Charlie Dowdall and Ernie MacKay would all go on to represent the nascent international team in the following years. Despite the chaos of the cup final replay over 25,000 spectators had paid in to watch the two games, bringing in gate receipts of over £1,000 which were crucial to the FAI’s finances in those early days.

Less than a week after the replay anti-treaty IRA volunteers, led by Rory O’Connor occupied the Four Courts in Dublin city. Tensions mounted and in the early hours of June 28th the Free State army began shelling the Four Courts from their positions south of the Liffey. The Civil War had begun, the nation was convulsed by almost a year of violence that would leave thousands dead. By the time a cessation to the violence arrived in May 1923, amid the turmoil, lawlessness and death somehow an entire football league season and cup competition had been played out. Circumstances that seem so utterly bizarre and unreal today. Shamrock Rovers, newly elected to the Free State league had won it at their first attempt. With Bob Fullam, returned from his ban, as top scorer. In the cup Alton United enjoyed their brief moment in the sun by winning the cup, a Belfast side triumphing in the Free State blue ribbon competition. A tragic, dramatic, scarcely believable, terrible state o’ chassis indeed.