They came across the narrow channel from the Antrim coast in the north-east of Ireland to the island of Iona in a wicker currach leaving behind conflict and bringing their religion to the neighbouring land. It was the year 563AD and their leader was Columba, a man now venerated as a Saint whose patronages include the lands of Ireland and Scotland and with him he rather appropriately brought twelve followers.

He certainly wasn’t the first Irish man to make this crossing. The Dál Riata kingdom of north Antrim had been expanding into western Scotland since the early 5th Century, even before that in the 3rd Century the Picts who lived north of Hadrian’s Wall had sought help from their Irish neighbours in their campaigns against Roman imperial might. Back then the Romans had referred to the tribes of northern Britain as the Caledonians, they called their Irish allies the Scotti.

In time Iona, where Columba landed became a great centre of learning and religious devotion and a prestigious Abbey was founded there. From Iona, the Picts were gradually converted to Christianity as were the Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria. In the centuries to come the name of the Scotti would become the name of the Gaelic speaking land north of the River Forth; Scotland – the land of the Gaels. Iona remained a focal point for centuries, it was a burial place for Scottish Kings who traced their power and authority back to the sacred island.

The medieval Abbey church on Iona

But if the Irish gave Scotland its very name and the beginnings of the Christian faith then the Scots can lay some claim to giving Ireland football. In 1878, so the story goes, John McAlery, a Belfast businessman was on his honeymoon in Scotland and went to watch a game of Association Football. The views of Mrs. McAlery on this matter are not recorded. Greatly enamoured with the game the sporty Mr. McAlery arranged for an exhibition game to take place later that year in the Ulster Cricket Grounds in Belfast between Scottish sides Queens Park and Caledonians with Queen’s Park running out 3-2 winners.

A year later he formed Cliftonville Association Football Club in his home city and they advertised for new players as a club playing under the “Scottish Association Rules”. By the end of 1880 McAlery, along with representatives from six other clubs had formed the Irish Football Association (IFA). Cliftonville F.C. exist to this day, while the IFA remains the 4th oldest Football Association in the world. While football had existed in Ireland before John McAlery it was he who set about putting in place a proper organisation and structure around the game. Had John taken his honeymoon somewhere other than Scotland then the history of football in Ireland may have been very different. Sadly the McAlery honeymoon story is definitely apochryphal but this hasn’t stopped it persisting. What is undeniable is that McAlery, and Scottish Clubs were at the forefront of the instigation of organised football in Ireland.

The game had grown quickly in the north east of Ireland and began in time to gain popularity in Dublin as well with the formation of clubs like Bohemian F.C. (1890) and Shelbourne F.C. (1895). A league was duly formed as well as cup competitions. But despite the good works of John McAlery and other early pioneers of the game Ireland’s early record in international competition makes for some harrowing reading. The international highlight in the early years was a 1-1 draw with Wales in 1883 sandwiched between a 7-0 loss to England and a 5-0 loss to Scotland. It would be 1914 before the Irish would win the annual Home Nations Championship outright, defeating Wales and England before facing Scotland knowing that if they avoided defeat they would triumph. Despite the match being held in Belfast Scotland remained the favourites, the Irish papers noting especially that the Scots were the more physically imposing side. However, in a torrential downpour a weakened Irish side managed to secure a draw and with it their first outright victory in the Home Nations Championship. They hadn’t beaten the Scots but they had won the day.

It was to be the last victory as a united Ireland though, not long after the end of the First World War the Football Association of Ireland (FAI) was formed as a breakaway association from the IFA. The FAI eventually secured recognition from FIFA and, grudgingly, from the Home Nations as the Association representing the 26 counties that would become the Republic of Ireland. What they could not secure however was favour from the Home Nations who refused all fixture invitations from the nascent organisation. Eventually over two decades later England agreed to a friendly in 1946, Wales waited until 1960 before playing the Republic. Scotland refused all invitations and only played the Republic when drawn against them in a qualifier in 1961. Despite their breakaway from the IFA the FAI remained in awe of the Home Nations and valued games against them more than any other, they fervently craved not only the money that these games would bring but also some sense of acceptance from their neighbours. Naturally this made the cold shoulder that they received all the more painful.

This desperation for acceptance can be encapsulated in a single game. In 1939 Ireland were due to play the Hungarians, who had been runners up to Italy in the 1938 World Cup and had played against Ireland twice before in the recent past. On both occasions the matches took place in Dalymount Park in Dublin. However on this occasion the match took place in the smaller Mardyke grounds of University College Cork and home to League of Ireland side Cork F.C.

So why were the World Cup runners up being asked to play in a University sports ground rather than at the larger capacity Dalymount? Well because there was a bigger game taking place in Dalymount just two days earlier on St. Patrick’s Day 1939, when the League of Ireland representative side were taking on their Scottish league counterparts.

Even a game against a Scottish League XI was viewed as a huge mark of acceptance from their Scottish peers. While the game in the Mardyke would attract 18,000 spectators, a respectable return, over 35,000 would pack into Dalymount Park to see the stars of the Scottish League. At the time commentators were moved to describe the match against the Scottish League as “the most attractive and far reaching fixture that had been secured and staged by the South since they set out to fend for themselves” before adding that “for 20 years various and futile efforts have been made to gain recognition and equal status with the big countries at home. Equality is admitted by the visit of the Scottish League”. For the FAI a game against any Scottish team was a game against giants.

Giants, funnily enough, feature prominently in Celtic mythology. Fionn MacCumhaill is arguably Ireland’s most famous character from myth, famed for his size and for his prodigious strength. He is credited with having created the Isle of Mann by scooping out the land of Loch Neagh and hurling it into the Irish Sea. However even a man of this power was no match for the Scottish giant Benandonner. In myth Fionn learns that Benandonner is coming for him in combat from Scotland and Fionn does the only sensible thing, he runs to his wife for help. Benandonner is so huge that Fionn fears that even he won’t stand a chance in a fight so he does what any man would do, he has his wife dress him up as a giant baby and put him sleeping in a cradle in front of his fire. When Benandonner arrives demanding to know where Fionn is, Fionn’s wife Oona tells him that he is out but will be back shortly. She introduces the “baby” as her and Fionn’s infant son. Seeing the size of the baby and not wanting to meet the enormous child’s father Benandonner flees back to Scotland, on his way he destroys the bridge that links Scotland and Ireland behind him. Folklore tells that Antrim’s Giant’s Causway was a left as the remnants of this destroyed bridge.

For the FAI the Scots remained giants. Like Benandonner they could not be beaten by force but only by cunning. In 1963 a 1-0 victory by Ireland over Scotland in a friendly was greeted with elation by the Irish football public as one of its greatest ever despite the narrow nature of the win.

While the awe in which the Scottish national team were held has faded significantly over the intervening decades the affection and devotion to one of her clubs remains as strong as ever. Writing as a Dubliner it sometimes seems impossible to avoid the prevalence of Celtic jerseys in my home city. In many ways this is understandable, while the island of Ireland might be grateful to John McAlery for bringing Scottish footballers to Ireland, the Irish in turn had a significant impact in creating the footballing landscape of Scotland. Beginning with the foundation of Hibernian F.C. in 1875 and continuing with the foundation of clubs like Dundee Harp, Dundee United and Celtic the Irish immigrant community and their descendants helped to create some of the most significant football clubs in Scotland.

This came about largely because of a period of mass migration of Irish people to Scotland from the 1820’s onward. Scotland’s industrial towns provided jobs, while Irish counties like Down, Antrim, Sligo and Donegal provided willing seasonable labour for Scottish factories, shipyards and farmers and this mass influx across the Irish Sea gathered apace after the Potato Famine began to grip Ireland in 1845. The parentage rule as introduced by FIFA has meant that the Irish national team have continually benefited from this immigrant connection even at the recent Euros two members of the Irish squad were Scottish born players; Aiden McGeady and James McCarthy.

Domestically clubs like Hibs and Celtic would emerge from these immigrant communities, often forming a charitable focal point at the centre of new Irish communities. While Hibs still prominently wear green and white and their current logo includes an Irish harp as a nod to their foundation (though it was removed from the crest for a period after the 1950s) they seem to be less defined by an Irish identity. Celtic however are for many the Irish club. This does have the tendency to cause some confusion for those fans of clubs actually based in Ireland.

Celtic’s Irish credentials are indeed impeccable. Founded in 1888 by Andrew Kerins an Irish Marist brother from Co. Sligo, (better known as Brother Walfrid), the club was created to support the poverty stricken Irish community in Glasgow. When Celtic Park was being opened in 1892 it was the Irish Nationalist and Land reform agitator Michael Davitt who laid the first sod, the turf brought over from the “auld sod”, Co. Donegal. Davitt would be made an honorary patron of Celtic, a position he also enjoyed in the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) who in 1905 would issue a ban on any member either participating in or even watching ‘foreign’ games.

“Foreign Games” meant anything that could be construed to be English, or indeed Scottish and as such obviously included Association Football which may have put the ageing Davitt in an awkward situation. The club have also had many prominent Irish players and managers associated with them throughout their long history; men such as Neil Lennon, Seán Fallon, Martin O’Neill and Packie Bonner, while even the likes of Roy and Robbie Keane have had brief Celtic cameos during their careers. In terms of ownership Irish businessman Dermot Desmond is the club’s largest individual shareholder. The early successes of Celtic helped prove that imitation was the sincerest form of flattery as in 1891 a group of Belfast sports enthusiasts from the Falls Road area formed Belfast Celtic F.C. Their early Chairman James Keenan noting that they chose their name “after our Glasgow friends, and that our aim should be to imitate them in their style of play, win the Irish Cup, and follow their example, especially in the cause of Charity.”

While all of this provides a strong basis for the popularity of the club in Ireland the other major aspect is of course that Celtic have been successful, from being the first British winners of the European Cup in 1967 to their 47 Scottish League titles theirs is a level of dominance, at least at domestic level, that is rarely seen. While as recently as the 2002-03 season Celtic reached the final of the UEFA Cup the fortunes of the club and the Scottish League in general have struggled recently when it has come to progress at European level. Despite this, support remains strong for the club in Ireland and their presence ubiquitous. Celtic flags and banners fly from Dublin city pubs while a musical treatment of Celtic’s history plays at present in one of the city’s most prominent theatres. In the commemorations to mark the centenary of the 1916 Rising the imagery of Celtic has been invoked as somewhat apocryphally one can purchase a “replica” Celtic jersey emblazoned with the name “Connolly” where once a Magners cider logo appeared. A reference to the Scottish born labour activist James Connolly who was among the leaders of the Rising; son of Irish immigrants he was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh and was a passionate Hibernian fan.

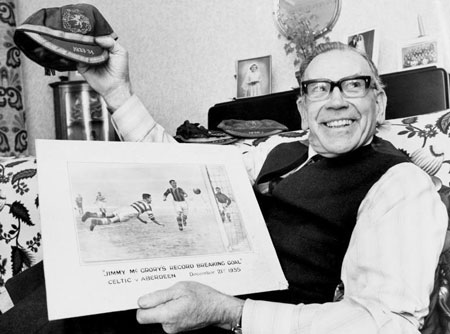

“Celtic the Musical” in Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre, an Irish tricolour next to a Celtic Flag at a restaurant in Temple Bar, a “replica” Celtic jersey featuring the name of executed 1916 leader James Connolly.

The stories of Fionn and Benandonner, the competing giants of Ireland and Scotland remain prominent stories in Irish folklore however they enjoyed a new lease of life in the 18th Century when Scottish poet James Macpherson compiled and re-framed the ancient myths into a book of poetry. The publication of his work was a literary sensation at the time but also caused debate and controversy as Irish historians felt their literature and history were being appropriated. The truth is that as we’ve seen with the historic patterns of movement and the shared culture between the two islands; from 6th Century monks to the Ulster plantations and the Famine migrations of the mid 19th Century, the two nations share far more similarities than some political groups and indeed football fans would care to admit. It was from Scotland that the original Irish football organisers took their inspiration but even by that stage the Irish in Scotland were already creating clubs that would help to dominate the Scottish football landscape. In a confused and confusing identity relationship it becomes hard to separate the interwoven strands of our social and sporting DNA. Where the Irish ends and the Scottish begins.

This article originally appeared in the Football Pink issue 14, they’re a great publication and well worth a subscription.