Bohemians and brothers in arms – The Robinsons

The great Bohemians team of the 1927-28 season is one that has rightly gone down in the annals as one of the finest sides in Irish football history; simply put they won everything there was to win, the League, the FAI cup, the Shield and the Leinster Senior Cup. An achievement all the more impressive when you remember that Bohs were strictly amateur at the time. Such was the confidence and camaraderie in the team that season that Jeremiah “Sam” Robinson, the tall, well-built and versatile half-back or full back, said that the Bohs players of that season never doubted that they would win the game, the only question was by how much. Sam was joined in that successful team by his older brother Christy, smaller and lighter than Sam, he was a tricky, skillful inside-left whose 12 goals had been crucial when Bohs won the league in 1923-24. He also holds the honour of scoring Bohemians first ever goal in the FAI Cup when he netted the first in a 7-1 win over Athlone Town in 1922.

For these achievements alone the brothers are significant and worthy of discussion, however by the time the Robinson brothers had joined Bohemians, as still young men, they had already led an extraordinary life. Both brothers had been active in the IRA in Dublin and Sam had even become a member of the Active Service Unit and later joined Michael Collins’ infamous “Squad ”.

Both brothers played in the Cup Final of 1928 when Bohemians defeated Drumcondra 2-1, although it was touch and go for Sam. Incidentally the reason Sam was known as Sam, and not by his given name Jeremiah was because of the fondness as a boy for using “Zam-buk” soaps and ointments for his legs, something he may have needed in getting ready for the Cup final. During some dressing room hijinks celebrating yet another victory Sam had his leg badly scalded by a bucket of hot water. The damage was so bad that it looked like he would miss the game until the intervention of Bohemians own Dr. Willie Hooper who bound up Sam’s leg (like a turkey cock as he later remarked) and tended to him regularly as they prepared for the final. The squad were worried that the Sam might not make the game but he was declared fit enough to play. Bohs won the match in front of 25,000 at Dalymount, Billy Dennis and Jimmy White getting the goals.

Bohemians have a long tradition of brothers playing in the same team. The aforementioned Willie Hooper and his brother Richard both captained Bohs in the early 1900’s while Sam and Christy had the distinction of becoming the first brothers to play for Ireland after the FAI had split with the Belfast-based IFA. Christy was part of the Irish Olympic squad that went to Paris in 1924 and defeated Bulgaria before being knocked out by the Netherlands in the next round. In all, six Bohemians were selected (Bertie Kerr, Jack McCarthy, Ernie Crawford, John Thomas & Johnny Murray were the others and were trained by Bohs’ Charlie Harris) The Irish team also played two friendlies after being knocked out of the tournament, Christy played and scored for Ireland in the game against Estonia as Ireland won 3-1 and would also represent the League of Ireland XI in their first ever representative fixture, against the Welsh League that same year. Sam won two senior caps, in 1928 and 1931 with a victory over Belgium and with a draw against Spain respectively.

Sam would eventually move on and play professionally for a period, he joined Dolphin F.C. based in the Dolphin’s Barn area of the city in 1930 and won his second Irish cap while there. He was also part of their team which contested the 1932 FAI Cup final, losing out to Shamrock Rovers in a tight game, while also guesting on a number of occasions for Belfast Celtic.

Christy and “Sam” were born in the Dublin’s north inner city on East Arran Street in 1902 and 1904 respectively, their home was close to the markets where their mother Lizzie worked as a fish dealer. Lizzie’s earnings had to support the family; the two boys and daughter Mary, when their father Charles died in 1905.

From left to right Christy, Lizzy and Sam Robinson

In 1916 as youngsters of 15 and 12 they would presumably have witnessed first-hand the fighting around the Four Courts just yards from their home and the family would likely have known some of the victims of the infamous North King Street massacre when British Army soldiers shot dead unarmed men and boys. Whatever the reason we know that by 1919 Sam, then aged only 15 had joined the IRA. He was a friend of Vinny Byrne who would also form part of the “Squad” and it was Byrne who brought him along to be inducted. At the time Sam lied about his age and claimed to be 17. The family story was that Michael Collins, on seeing young Sam told the boy that he wasn’t running a nursery and he should go home, however Sam insisted that he wished to join and both Byrne and Paddy Daly (one of Collins’ senior officers) vouched for the young man. It was to begin a long association between Sam and the armed forces.

Christy, also joined the IRA and took part in a number of notable actions, the most prominent probably being the raid on a British Army party at Monk’s bakery on Church Street in September 1920. This was the operation in which Kevin Barry was captured. Christy Robinson was one of the section commanders within H company of the 1st Battalion, Dublin brigade of the IRA during the raid when they encountered a much larger British army force than expected. Kevin Barry found that his new-fangled automatic pistol was jamming and hid under a lorry hoping to escape the attentions of the British forces. After heavy gunfire which left three British soldiers dead, H company withdrew but were unaware that Kevin was still hidden under the lorry on the side of the street. The unfortunate teenager was spotted by the British forces, arrested, and later became the first Republican prisoner to be executed since the Easter Rising over four years earlier.

Kevin Barry had attended the prestigious Belvedere secondary school and had been a promising rugby player. He had graduated and was studying medicine, in fact he intended to go sit an exam only hours after the raid on Monk’s bakery and was not a full time soldier. Christy would later christen his son, Kevin in honour of his executed comrade. Christy later joined the Free State Army and rose to the rank of Captain before leaving in 1924. After his football career Christy would move to England, first to London and later to Dover, where he would pass away in 1954.

Most of the members of the Dublin Brigade were men who took part in operations when they could but had to hold down jobs in order to support themselves and their families. Christy Robinson fell into this category. The IRA however saw the need for a full time force of both soldiers and intelligence staff. This led to the creation of the Active Service Unit (ASU); full time soldiers who were expected to make themselves available as operations required them, they were paid a good wage for the time. Sam Robinson would eventually join this select group of full time soldiers; a role he would continue after Independence.

The Robinson family had been victims during this period of bloodshed, two of the brothers’ cousins met violent ends just weeks apart in 1920. William Robinson, a former British soldier and a goalkeeper for the Jacobs football team was shot dead on Capel Street, just yards from his home in October 1920 by men identifying themselves as “Republican Police”. Another cousin, also named William, but better known as Perry Robinson was one of the youngest victims of the Bloody Sunday shootings in Croke Park. Aged just 11 years old Perry was shot in the shoulder and chest as he was perched in a tree watching Dublin take on Tipperary. The trainer of the Dublin side that day was none other than Bohs’ own Charlie Harris who would accompany Christy Robinson to the Paris Olympics just four years later.

The Dublin Football team on Bloody Sunday- Bohemians trainer Charlie Harris is at the back row, far right.

The Robinson family history tells that Sam was out that morning that would be remembered for all time as “Bloody Sunday”, in the company of his friend Vinny Byrne. Their destination on that fateful day was 28 Upper Mount Street, their targets British Lieutenants Aimes and Bennett. This was a late change to the plans due to a recent piece of intelligence received by one of Collins’ intelligence officers, Charlie Dalton who was also at the time also a member of Bohemians. Byrne and fellow Squad member Tom Ennis led the party. Although not named in these accounts Sam always claimed that he was out with Byrne and his group that day when Aimes and Bennett were shot dead in their beds, Byrne’s own witness statement mentioned that there were a party of about ten men involved and that the operation did not go as smoothly as hoped. The sound of shooting aroused the attention of other British military personnel in the area and the men keeping an eye on the entrance to Mount Street came under fire. Most of the party fled to the river and rather than risk crossing any of the city bridges back to the north side where they could be intercepted. They crossed by a ferry and disappeared into the maze of streets and safe-houses of the north inner city.

Not long after the events of Bloody Sunday Sam became a full time member of the “Squad” when it was reinforced in May of 1921. Within weeks they would be pressed into service in one of the largest operations ever undertaken, the attack on the Custom House, one of the centres of British administration, local Government and home to a huge amount of records.

Sam being arrested at the Custom House, he is fourth from the right with his hands on his head.

This was going to be a huge job and a symbolic attack at one of the nerve-centres of British rule in Ireland, up to 120 men of the 2nd Dublin Brigade along with members of the Squad and the Active Service Unit took part. They were poorly equipped, armed only with revolvers and a limited supply of ammunition, they did however have plenty of petrol and bales of cloth which was used to destroy the records and ultimately the building itself which burned for five days straight. The raiding party soon drew the attention of a brigade of Auxiliaries. Unable to stay in the burning building, surrounded by the British forces and very quickly running out of ammunition the Republican forces knew they were in serious difficulty. Most of the men surrendered but some made a run for it, a few escaped, but others like Sean Doyle were killed as they tried to get away. Among the more than 70 IRA men captured was Sam Robinson, although he was not to be in captivity long. Within two months a truce had been called and the Treaty negotiations had begun and Sam was released by Christmas of 1921.

Upon his release Sam became part of the new Free State Army, by the 1922 Army census he was listed as a Lieutenant and he was heavily involved during the Civil War, seeing action in areas of some of the heaviest fighting around Cork, Kerry and later Sligo. He was in the Imperial Hotel in Cork City along with other serving officers to have breakfast with Michael Collins the day he was shot. Despite Collins’ initial scepticism about this teenager who had lied about his age to join the IRA he had trusted and promoted Sam. In turn Sam, like many other officers became a great admirer and loyal follower of the “Big Man” and was devastated to learn of his death at Béal na Bláth. In another freak Bohemians connection, the man who tended to Collins as he died was General Emmet Dalton, a former Bohemian F.C. player and later President of the Club.

Sam was promoted to the rank of Captain in February of 1923 and remained in the Army throughout the horrific violence of the Civil War but left, somewhat disillusioned, in 1924. There was concern among members of the Free State army about plans to significantly decrease the size of the army in peacetime and there was also a feeling among some soldiers that ex-British army officers were being favoured for advancement within the Free State forces. Such was the seriousness of this issue that Charlie Dalton (the ex-Bohs player we encountered above, and brother of Emmet Dalton) and General Liam Tobin were accused of attempting an Army Mutiny due to their opposition to the proposed demobilisation.

Sam in his Irish Army uniform

The army’s loss was Bohemians gain however and the civilian Sam Robinson joined his brother at the club and helped build towards the eventual dominance of the 1927-28 season. It was not to be Sam’s last involvement with the Army however, upon the declaration of the national state of Emergency during World War II Sam re-enlisted and was made a Captain of C Company of the 14th Battalion, his years of experience no-doubt appreciated by younger troops. He stayed in the Army until the end of the War before returned to the trade he had developed as a plasterer. In fact he started his own plastering company, Robinson & Son near Church Street in Dublin.

Things went well for Sam’s business for a while and he was a generous man always making sure that old Army or footballing colleagues were helped out with a job if they fell on hard times. Among those employed at one stage by Sam was his former Bohs team-mate John Thomas. However, in 1957 perhaps because of his generosity, Robinson & Son went out of business, Sam’s auditor incidentally at the time was a young man by the name of Charles J Haughey! While this was a setback Sam used it as an opportunity to travel, his trade took him to Canada, Malta, Britain and even Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) before he returned to Ireland. Fate would have it that one of his final jobs as a plasterer was on the Phibsboro shopping centre, overlooking the pitch at Dalymount that had been so familiar to him.

Sam’s connection with Bohemians continued long after his playing days ended. His nephew Charlie Byrne began his career for Bohemians in the 1940’s , while his son Johnny Robinson enjoyed a successful League of Ireland career with Drumcondra and Dundalk. Sam remained a Bohemian member until the day he died in 1985.

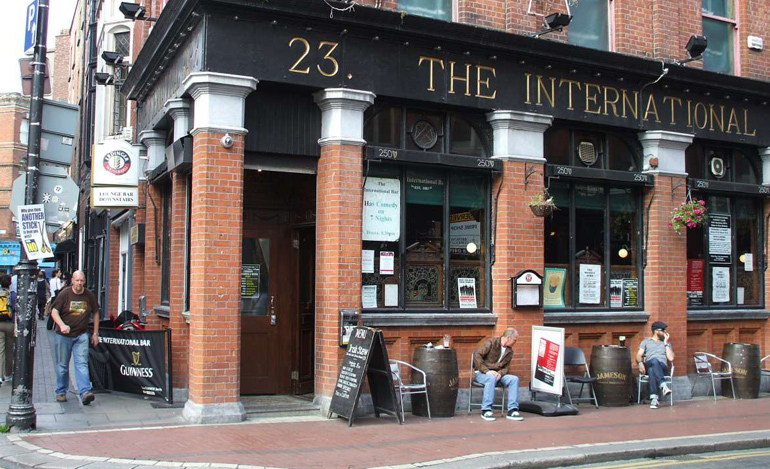

The Bohemian membership card of Jeremiah “Sam” Robinson

With special thanks to Eamon Robinson, Frank Robinson and Kevin Robinson for their assistance and sharing their family research and photos.