The Death of Sex

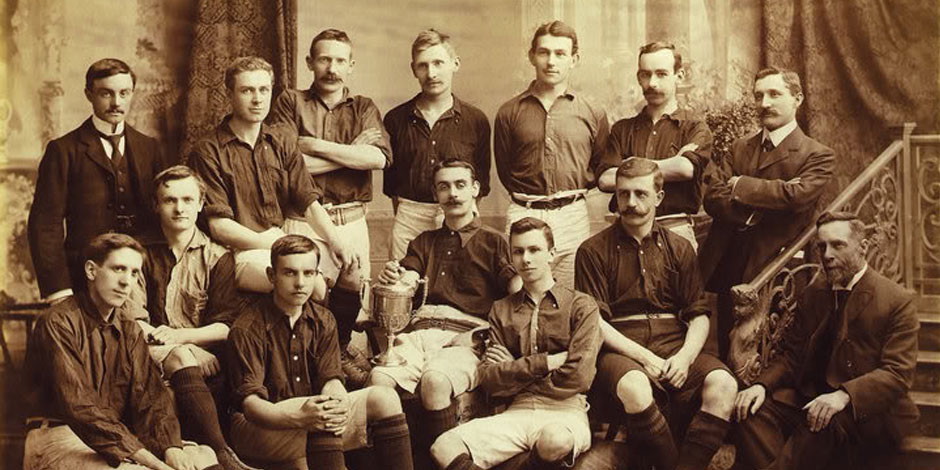

It started in somewhat unusual fashion, a Whatsapp chat with some fellow historians, a screenshot from the Irish Newspaper archive with the unusual headline “Replay for Sex Memorial Gold Medals”, which of course provoked a bit of schoolboy humour but also planted a seed of curiosity. From the short clipping I could see that it was a replayed football match between Bohemians and a Leinster football XI, the Bohemian teamsheet was shown and I could tell that this was a game from the early 1920s with several high profile players featuring, including future internationals like Joe Grace, Jack McCarthy, John Thomas and Johnny Murray as well as South African centre-half Billy Otto.

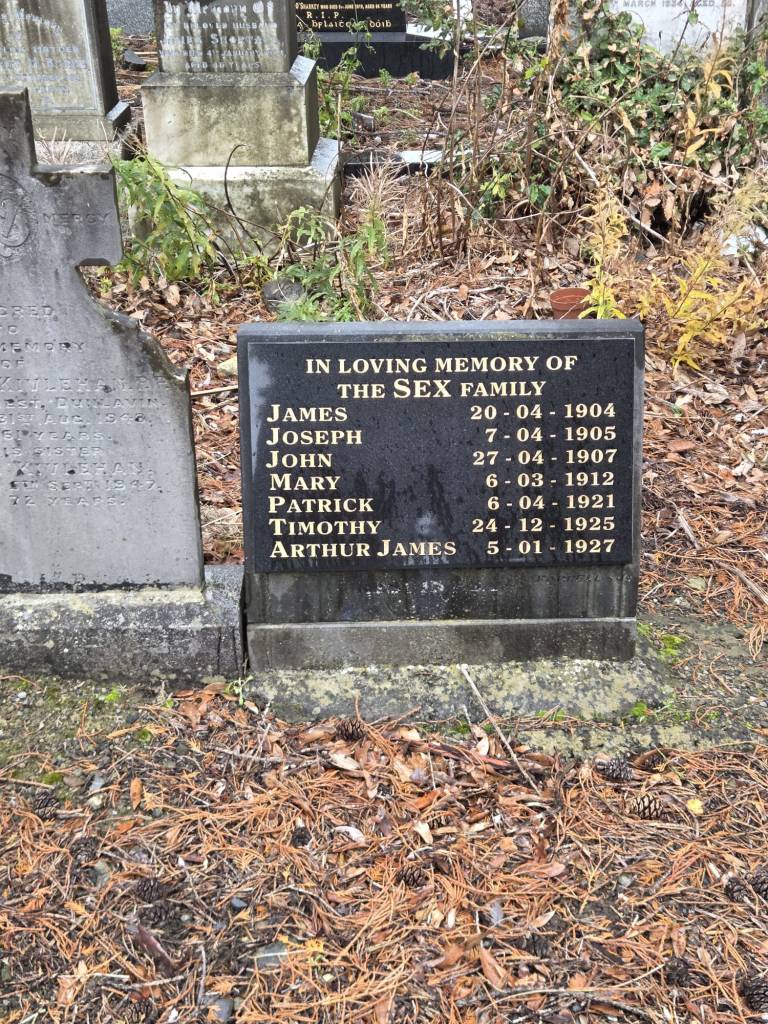

But who or what was “Sex” referring to? Memorial games or charity matches for sets of gold medals were not uncommon in the era but I could find nobody with the surname Sex as having been associated with Bohemian FC in their first thirty or so years, and as the opposition were a selection of other Leinster based players then there was no specific opponent club who might have been arranging a memorial. A quick look at the 1911 Census suggested a possible answer, as it displayed 22 people with the surname “Sex” living in Dublin.

Having ascertained that there indeed may be a “Sex” living in Dublin, deserving of a memorial game, but unsure of any footballing connections I started searching the Irish newspaper archives for the early 1920s and quickly discovered a likely candidate for the “Sex Memorial Gold medal match”, namely Patrick Sex of Dominick Street in Dublin’s north inner city with the memorial match and replay taking place for him in May 1921.

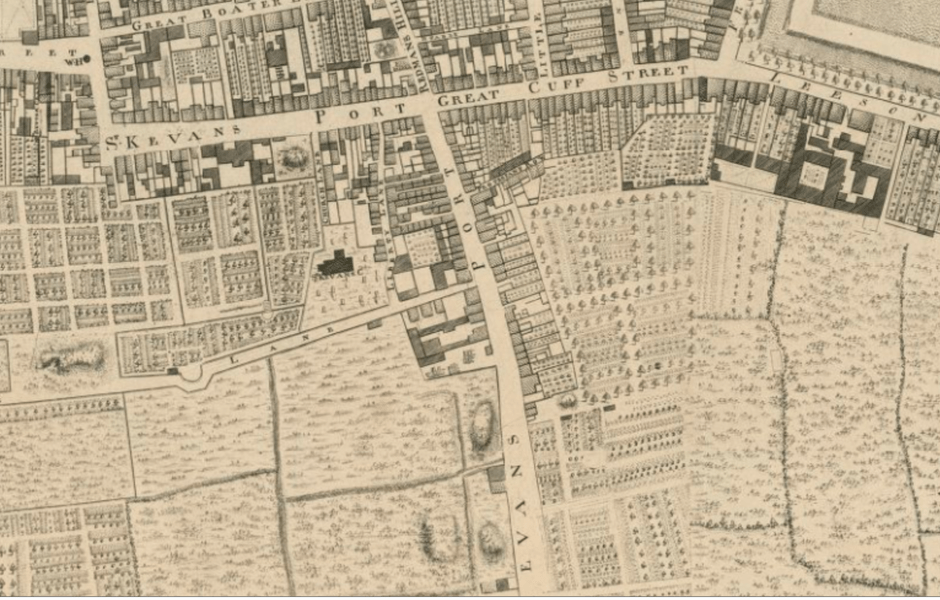

Patrick Sex was born in Dublin in 1880 and by the time of his marriage to Mary Kenna – a dressmaker living in Mary’s Abbey off Capel Street – in September 1901, he was living in Coles Lane, a busy market street off Henry Street and working as a butcher. Coles Lane, which now leads into the Ilac Centre but once ran all the way to Parnell Street, was full of stalls and shops selling everything from clothing to meat, fish and vegetables and formed part of a warren of streets and lanes feeding off the busy shopping areas of Henry Street and Moore Street. The area was a booming spot for a butcher to find work, it is likely that Patrick was raised and apprenticed in the trade as “butcher” is listed as his father James’s trade on Patrick’s marriage certificate.

Patrick and Mary, welcomed a son, James in August 1902 and they moved around the same small footprint of this section of north inner city Dublin in the coming years, with addresses on Jervis Street, Great Britain Street (now Parnell Street) and Dominick Street. It is on Dominick Street where we found the Sex family living in the 1911 Census, by which point they have five children, with one-year-old Esther being the youngest and Patrick was still working in the same trade, being listed as a Butcher’s Porter.

Moving forward ten years to 1921, the year of Patrick’s violent and untimely death, and the family had a total of ten children and were still living at 72 Dominick Street. Patrick was still working in the butchery trade in McInnally’s butchers at 63 Parnell Street, close to the junction with Moore Lane, roughly where the Leonardo (formerly Jury’s) hotel is today and would have been close to Devlin’s Pub, owned by Liam Devlin and a popular meeting spot for the IRA during the War of Independence.

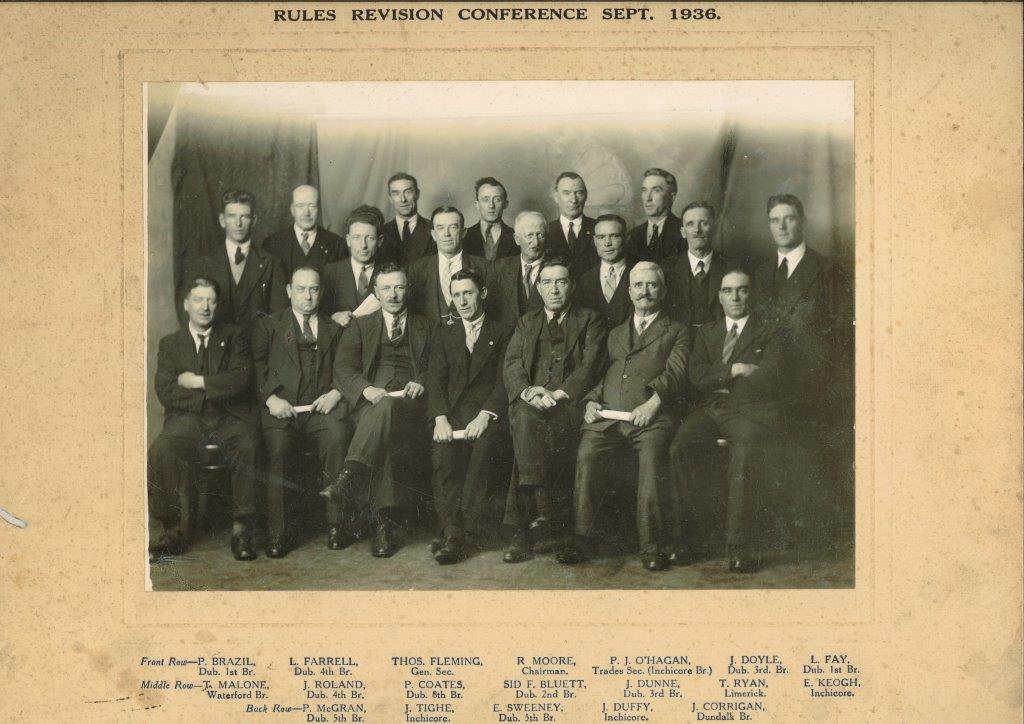

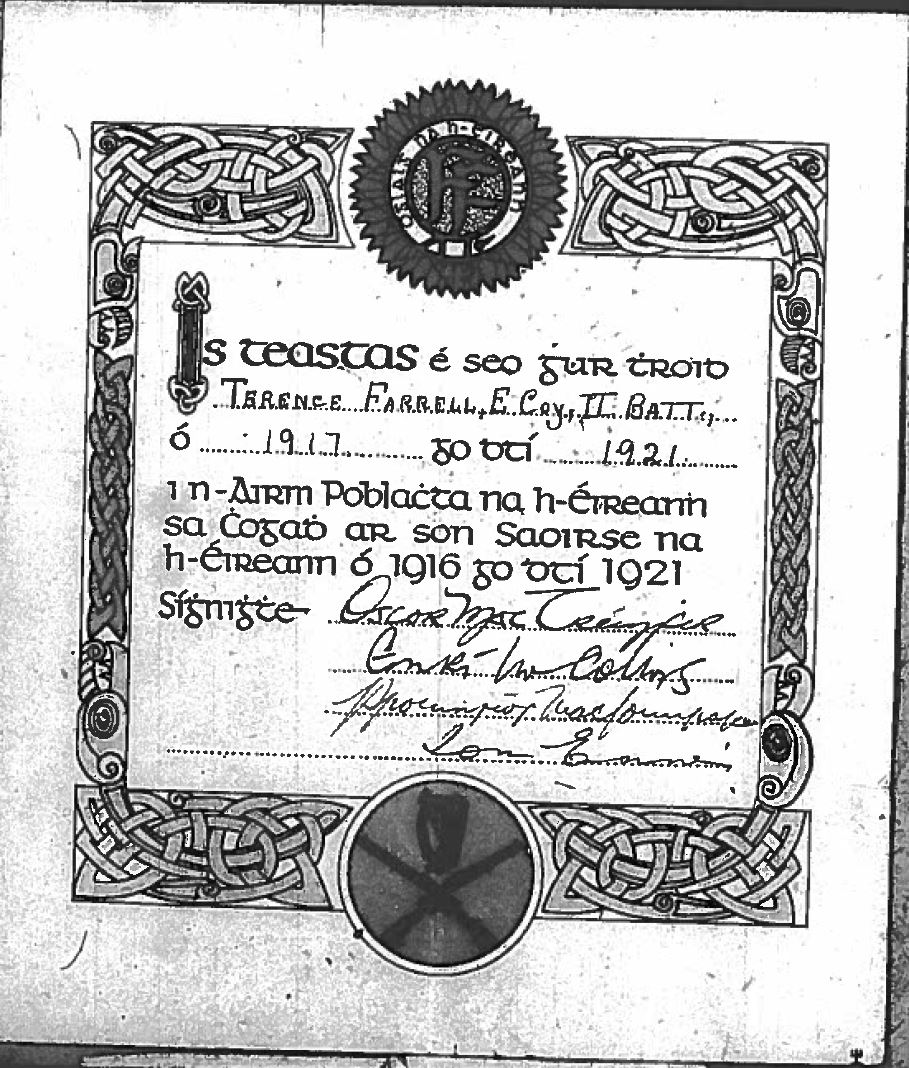

By this stage in his life, as well as his place of work and large family we know that Patrick was active in the trade union movement, being Chairman of the No. 3 branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), this branch featured many from the butchers’ trade and was known as the Victuallers’ Union. Living and working where he did, no doubt Patrick would have clear memories of the Lock-out in 1913 and the infamous baton charge by the Dublin Metropolitan Police on Sackville Street in August of that year when two workers were mortally wounded.

On March 26th 1921, Patrick Sex was, as usual, working at McInnally’s butcher’s shop on Parnell Street, it was owned by Hugh McInnally, originally from Scotland he had set up a number of butcher’s shops in Dublin and by the 1920s was entering his 70s and living in some comfort near Howth. The city and country more broadly were far less comfortable – more than two years into the violent period of the War of Independence, Dublin had seen the city placed under curfew in February 1920, there had been wide scale arrests, November 1920 had seen Bloody Sunday when fourteen people were killed in Croke Park by Crown Forces in reprisal for the wave of assassinations earlier that morning by the “Squad” and the Active Service Unit of the IRA. Croke Park was just a few minutes walk from Patrick’s home and place of work, he likely knew many who had attended the match, or perhaps some of those arrested in the wide scale arrests across the city by Crown Forces that followed. As mentioned, McInnally’s butcher’s was just doors away from an IRA safe house and meeting place in Devlin’s Pub, while Vaughan’s Hotel was just around the corner on Parnell Square.

This was the backdrop against which Patrick Sex and his family lived and worked in Dublin. On that fateful day of the 26th just before 3pm a lorry, carrying Crown Forces was attacked by members of “B” company of the 1st Dublin Brigade of the IRA as they journeyed up Parnell Street. The brigade report, taken from the Richard Mulcahy papers reads as follows;

“8 men… attacked a lorry containing 16 enemy at Parnell Street and Moore Street. 3 grenades exploded in lorry followed by revolver fire. Enemy casualties believed to be heavy. The lorry drove into O’Connell Street and was again attacked by a further squad of this coy. [company] numbering 18 men. They attacked another lorry at Findlater Place but were counter-attacked by lorry coming from the direction of Nelson’s Pillar. 3 of our grenades failed to explode so we retired. One of our men was slightly wounded”.

The Freeman’s Journal, reporting on the attacks a couple of days later goes into more detail on the impact of the grenade and gun attacks as they affected the public caught in the melee;

“the first bomb was thrown and exploded with a great crash in the channel opposite MacInally’s (sic) victualling establishment, 63 Parnell Street. The explosion was followed by a wild stampede of pedestrians.”

They continued: “The glass and woodwork of the houses from 63 to 66 Parnell Street were damaged by the flying fragments of the bombs. Mr. Patrick Sex, an assistant in the victualling establishment of Mr. MacInally was wounded in the hip and leg… and others in the shop had narrow escapes from the contents of the bomb, which in the words of Mr. O’Doherty ‘came through the shop like a shower of hail’.”

John O’Doherty the butcher in McInnally’s, mentioned above, would give a statement to a subsequent court of inquiry at Jervis Street Hospital, stating that he heard “two explosions and three or four shots”, before adding that “several fragments of the bombs came into the shop, and Patrick Sex who was attending a customer at the time said ‘I am struck’ , I saw that he had a wound in his left thigh and hurried him off to hospital.”

Another of those to give testimony at the court of inquiry (inquests into deaths had been suspended during the War of Independence) was Charles Smith of the RAF, he was in one of the Crossley Tender lorries, with two other RAF men in the driver’s cab as it made its way up Parnell Street, when he recalled that a man armed with a revolver stepped into the street and shouted “Hands up” and “Stop” at which point “3 or 4 other civilians fired at us, the driver was immediately hit and collapsed in his seat. Several bombs were thrown at us, as far as I know three or four.”

The driver who was hit was Alfred Walter Browning, a nineteen year old RAF recruit from Islington. He was taken to the King George V Hospital (later St Bricin’s Military Hospital) at Arbour Hill where he died later that evening. The other passenger was David Hayden from the Shankill in Belfast, he was badly injured but survived. All three men were based at the airfield in Baldonnell which was in use then as a RAF base. There was another fatality related to the attack on the lorry at Findlater Place, just off O’Connell Street, when 15 year old Anne Seville was struck by a ricocheting fragment of a bullet as she watched the fighting below from her bedroom window. Despite an operation in an attempt to save her life she passed away two days later.

But what of Patrick Sex? His wound was deemed to be not particularly serious, he was brought to Jervis Street hospital and initially it seemed that everything would be alright. Patrick was seen by Dr. L.F. Wallace who also testified before the inquiry and he stated that there was a wound to Patrick’s left thigh, with no corresponding exit wound. Despite being admitted on the 26th March, Patrick was not thought in need of emergency surgery and was not operated on until April 4th when an “irregular piece of metal” about half an inch long was removed from his thigh. However, despite all seeming to have gone well Patrick contracted tetanus and his condition immediately worsened, he only survived until April 6th. His death notice read “cardiac failure following on tetanus caused by a wound from a fragment of a bomb”.

This left Mary, widowed with a family of ten children to support, and while it may not even have been known yet by Mary and Patrick, she was pregnant with their eleventh child, who would be born in November of that year and would be christened, Vincent Patrick by his mother.

Mary hired prominent solicitor John Scallan who had offices on Suffolk Street in the city centre to pursue a claim for compensation from the Corporation of Dublin and the Provisional Government in January, 1922. Scallan’s letters to the military inquiry requested information on the outcome of the inquiry and a list of any witnesses that they could call, the letter also incorrectly states that Patrick Sex was wounded by a bullet and not a bomb fragment. These claims were reported on in May, 1922 with it being stated in the Freeman’s Journal that a claim for £5,000 had been lodged by Mary Sex “in respect of the murder of her husband, Patrick Sex”. The article describes the compensation claims as those “alleged to have been committed by any of the several units of the British forces in Ireland”. While Patrick was an innocent bystander from the medical reports it would seem a bomb fragment from a grenade thrown by members of the Dublin Brigade, rather than a British bullet was the ultimate cause of his death. It was reported that by November 1922 over 10,000 claims for compensation had been made.

While Mary lodged that claim in January 1922, after the ceasing of hostilities and the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty, she still had to provide for her large, and growing family. The tragic case of Patrick’s death had clearly struck a particular chord among the Dublin public, despite the amount of violence and death they had witnessed over the previous two years. Perhaps it was the fact that he left a widow and ten children, his role as a prominent trade union organiser, or perhaps it was also the fact that several newspapers, including Sport, The Freeman’s Journal and The Dublin Evening Telegraph had reported that Patrick had sustained his injuries while protecting others leant even greater emphasis to his harrowing story.

The mention that Patrick had protected others is hard to confirm but from piecing together accounts in various newspaper reports it seems that Patrick may have shielded a child who was in the shop from the blast, possibly the child of an Annie Flynn who was mentioned as also being injured by the grenade blast, (see header image) though this is not specifically mentioned by John O’Doherty, the one witness at the inquiry who had seen Patrick get hit by the bomb fragment.

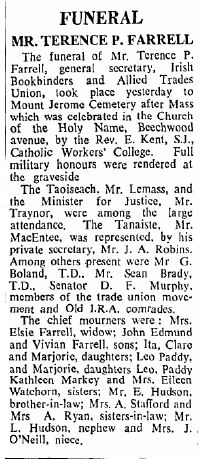

Patrick’s funeral took place on the 11th of April in St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, just a couple of minutes walk from his place of work. There was a huge crowd in attendance, estimated by the Evening Herald as numbering as high as two thousand with the funeral described as “one of the largest witnessed in Dublin for a considerable period”. As well as family mourners there was a strong representation of Patrick’s trade union colleagues, they presented a large floral wreath in the shape of a celtic cross. His funeral cortege passed through a Parnell Street which shut all its shops in a sign of mourning and was then met by more of the ITGWU branch members at Cross Guns bridge where they took the coffin from the hearse and carried it to Glasnevin cemetery for burial.

The burial itself was somewhat unusual as the gravediggers at Glasnevin cemetery were on strike, which they would not break, even for a fellow union man, so Patrick’s grave was dug and closed by friends and family members. Gravediggers’ strikes were not uncommon at the time, they had taken place in 1916, 1919, and again in 1920. The one exception made by the gravediggers during their strike did take place a couple of days before Patrick’s burial, for the internment of Dublin’s Archbishop, William Walsh.

The outpouring of public support for the Sex family was evident not only in the strong turnout for Patrick’s funeral but also in the sporting world. A memorial committee had been established and a month after Patrick’s funeral there was to be an end-of season benefit match staged in Dalymount Park between Bohemians and a Best of Leinster XI, a set of high-quality gold medals were to be presented to the winning team while the proceeds from the game would go to help Mary Sex and her children.

The game was played on the 18th May, 1921 and a crowd of around 4,000 was in attendance to witness an entertaining 2-2 draw. With no extra-time and no penalty shoot-outs a replay to decide the winner of the gold medals was set, which also guaranteed a second opportunity to fundraise for the Sex family. After some back and forth around a replay date, the 26th May was chosen and Dalymount Park was once again the venue, this time Bohemians were the victors, triumphing 1-0 over the best of Leinster selection, thanks to a goal by Billy Otto. It was said that the game was played “before a good attendance” and this hopefully translated into funds for Patrick’s family.

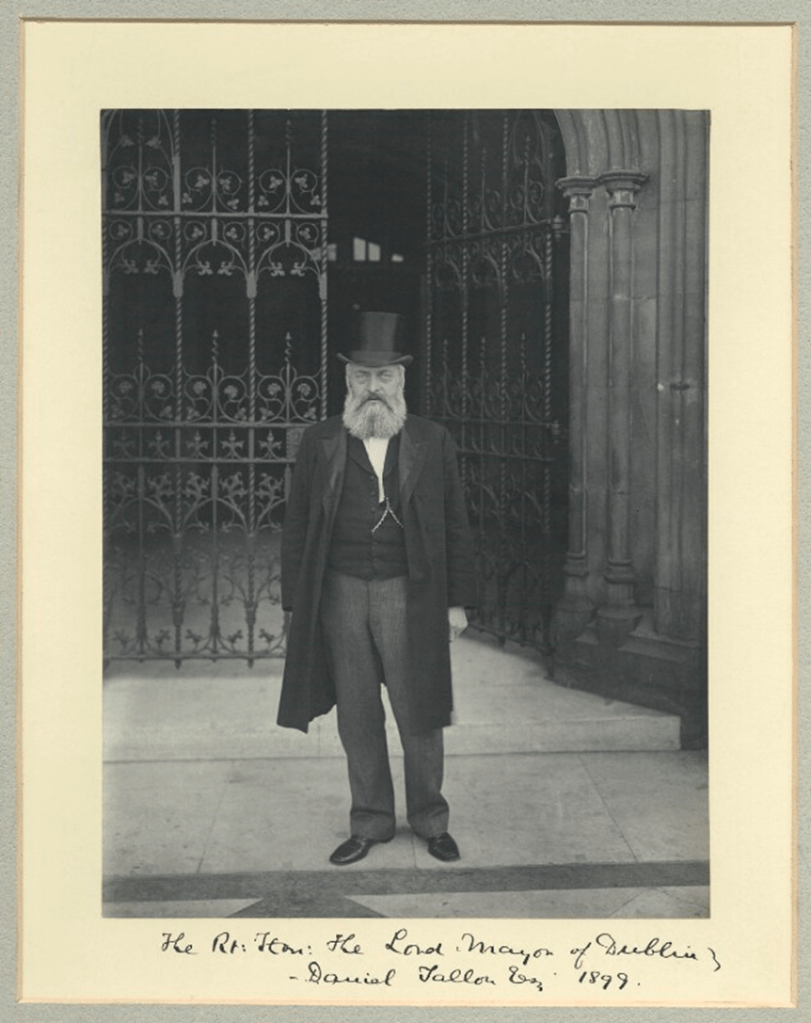

It had been suggested in a Dublin Evening Telegraph report that Laurence O’Neill, the Lord Mayor of Dublin might ceremonially kick off the game, but this did not happen due to his having to travel to the USA where O’Neill was working with the “White Cross” who were providing aid in Ireland during the War of Independence. It was suggested in O’Neill’s absence that W.T. Cosgrave, then an Alderman on Dublin City Council, might take over that role but it is not clear from reports whether this happened.

The same report stated that “this is the first time the Dublin footballers and supporters have come forward to do something the alleviate the sorrow of at least one household in these unsettled days” while also encouraging those who did not attend football matches to “rid themselves of all petty prejudices and bring all their friends and associates for the once to Dalymount”. Which would appear to be a not so subtle appeal to supporters of the GAA codes to ignore “the Ban” and attend a soccer match due to the good cause that it was supporting.

One final question that arises, considering the level and scale of violence witnessed over the previous two years, why was Patrick Sex the first victim of the violence in the War of Independence to receive a benefit match? While Patrick Sex may have been a football fan, though it is not specifically mentioned in any reports, he doesn’t seem to have been mentioned in any role in connection with any club or with the Leinster Football Association (LFA). As previously discussed the size of Patrick’s family, his role in the Trade Union movement, and being well known in the local area having worked for many years for McInnally’s butchers all contributed to the prominence given to his funeral, but he was sadly far from unique. Many people with large families, who were well known within their communities lost their lives during the War of Independence, so why a football benefit for Patrick if we can’t find any specific connection of Bohemians, the LFA or any other football club?

I would suggest the answer lies in the timing of Patrick’s death in April 1921, with the benefit match and its replay being held the following month. For context, long-standing issues within the Belfast-based Irish Football Association and its relationship with the LFA and its member clubs were coming to a head against the backdrop of internal bureaucratic strife and the ongoing violence of the War of Independence. In February 1921 there are been consternation among the IFA officials at the displaying of an Irish tricolour at an amateur international against France in Paris, those involved were arrested and there were charges within Dublin football and local media of bias on the part of the IFA. The IFA had also made the decision to not play that season’s Junior Cup and move Intermediate Cup matches which had been scheduled for Dublin to Belfast. The final straw arrived in March 1921 when the venue for a replay of the drawn Cup game between Glenavon and Shelbourne came to be decided. The original match had taken place in Belfast so custom would suggest that the replay should take place in Dublin. However, the IFA ruled that the replay should also take place in Belfast.

On June 1st, less than a week after the Sex memorial match replay, at the annual meeting of the LFA in Molesworth Hall in Dublin, an overwhelming majority of committee members voted to break away from the IFA. The LFA had been polling its member clubs on the subject since April before passing the motion at the beginning of June and by September of that year the Football Association of Ireland had been established, and surprisingly quickly new League of Ireland cup and league competition had also been formed.

As Neal Garnham notes “by mid-May the LFA was effectively operating independently of the IFA”. Somewhat bizarrely the IFA held a Council meeting on June 7th, seemingly blissfully unaware that the LFA had voted to remove itself from IFA jurisdiction, among the items voted on and approved at the meeting was a motion by Bohemians to play a benefit match for Patrick Sex. It perhaps, shows the sporting and communications division between Belfast and Dublin, that the IFA were unaware that the LFA was no longer affiliated, or that two benefit matches for Patrick Sex had already been played. The organising of the game by Bohemians, the LFA and the role of the memorial committee which seems to have included prominent Republican politicians like Laurence O’Neill and W.T. Cosgrave, seems to suggest that the Patrick Sex memorial match was part of a larger, ongoing process of Dublin football moving away from Belfast control and taking charge of its own affairs, this coupled with the specific nature of Sex’s death and his background suggests why he, and not some other innocent victim was the first to receive such a benefit game.

With special thanks to Aaron Ó’Maonigh, Sam McGrath and Gerry Shannon for their help with elements of the research, and for Aaron for sending on the original “Sex memorial” clipping.

The one shown below was minted in Dublin by John C. Parkes of The Coombe and he was responsible for striking most of the pub gambling tokens.

The one shown below was minted in Dublin by John C. Parkes of The Coombe and he was responsible for striking most of the pub gambling tokens. While Grafton Street isn’t too well known for pubs today the Duke Pub, back on Duke Street is named after the 2nd Duke of Grafton Charles Fitzroy. Originally opened in 1822 the Duke Pub was run by a James Holland when they first started issuing their own tokens in the 1860’s. Since that time the pub has expanded and has taken over premises that once housed the famous Dive Oyster Bar and part of the hotel building that was operated by Kitty Kiernan and her family. It was for a time known as Tobin’s pub but has since reverted back to the original name of the Duke Bar. After a chat and a drink with David, the bar manager we were due to head onto our final watering-hole, north of the river this time to Brannigan’s of Cathedral Street.

While Grafton Street isn’t too well known for pubs today the Duke Pub, back on Duke Street is named after the 2nd Duke of Grafton Charles Fitzroy. Originally opened in 1822 the Duke Pub was run by a James Holland when they first started issuing their own tokens in the 1860’s. Since that time the pub has expanded and has taken over premises that once housed the famous Dive Oyster Bar and part of the hotel building that was operated by Kitty Kiernan and her family. It was for a time known as Tobin’s pub but has since reverted back to the original name of the Duke Bar. After a chat and a drink with David, the bar manager we were due to head onto our final watering-hole, north of the river this time to Brannigan’s of Cathedral Street.