The Dalymount Falls – solidarity with Belfast in a time of crisis

Against a backdrop of the War of Independence and a city consumed by sectarian violence, thousands of Belfast’s shipyard and engineering workers found themselves expelled from their jobs for reasons ranging from their religion to their political affiliation. Many of these men found solace and indeed, the money to get by, through football. Cup tournaments for expelled workers were created and fundraising initiatives launched. At a pivotal time for the development of football in Ireland many clubs, including Bohemian FC, were to the fore in showing solidarity with the expelled workers of Belfast. This is my attempt to tell at least part of that story.

On the 12th of July 1920, Edward Carson, the Dublin-born icon of Unionism made an impassioned and inflammatory speech in a field in Finaghy, some four miles from the centre of Belfast, in front of an estimated crowd of 25,000. He railed against the dangers of a Sinn Féin invasion and stressed that, if needed, Ulster Unionism would oppose Home Rule by force, referring to secret plans by prominent Unionist politicians to resurrect the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). He then finished with quite the rhetorical flourish –

“We must proclaim today clearly that come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin – no Sinn Féin organisation, no Sinn Féin methods… And these are not mere words. I hate words without action”.

Edward Carson – 12th July 1920

Some Unionists had been shocked when earlier in the year Sinn Féin candidates had made significant gains in local elections across Ireland, including taking control of local Councils in several Ulster Counties. There was also the obvious backdrop of the escalating violence of the Irish War of Independence as further cause for concern. In March 1920 the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomás Mac Curtain was murdered in front of his family by members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) under the orders of RIC District Inspector, Oswald Swanzy. Three months later Lieutenant-Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, a British Army officer seconded to the RIC made an incendiary speech to members of the RIC in Listowel, Co. Kerry regarding the methods which he wanted to see deployed in dealing with the Volunteers, culminated with the reported lines;

You may make mistakes occasionally and innocent persons may be shot, but that cannot be helped and you are bound to get the right persons sometimes. The more you shoot the better I will like you; and I assure you that no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man and I will guarantee that your names will not be given at the inquest.

Lieutenant-Colonel Gerald Smyth (RIC) – June 1920

These events specifically would have a bearing on what was to come in Belfast and other parts of Ulster. While the 12th of July holiday had passed off peacefully, on the 17th of July, Gerald Smyth, targeted in part as a reprisal for his speech, was shot dead by the IRA in the smoking rooms of his members club in Cork. His body was taken to Banbridge, Co. Down, where his mother’s family had come from, for burial. It was after his burial on 21st July that most workers in Belfast returned to their jobs after the holiday break. The timing was bad and discussion quickly moved from the funeral of Smyth to Catholic workers in the Belfast shipyards and other related industrial sites, members of the Belfast Protestant Association had put up posters on the gates of Queen’s Island (Belfast Harbour) calling for a meeting of “all Unionist and Protestant workers” for lunchtime that day. Members of the militant Belfast Protestant Association made “very angry and hot” speeches to assembled workers from the Harland and Wolff and the Workman Clark yards, with the result that as many as a thousand workers then swept into the Harland and Wolff yards looking for Catholic workers and so-called “rotten Prods”, those viewed as Socialists or not sufficiently loyal to Unionism. It had not been lost on the mob that Carson in his speeches had also attacked ‘men who come forward posing as the friends of labour’, whose real object was ‘to mislead and bring disunity amongst our own people; and in the end, before we know where we are, we may find ourselves in the same bondage and slavery as is the rest of Ireland’.

Men had their shirt collars torn open as members of the mob searched for religious medals, while some even dived into the Musgrave channel and swam for their lives to escape the violence being meted out. The violence continued to grow and extended beyond the confines of the shipyards and became focused on neighbouring streets and businesses, trams were attacked and workers aboard, fleeing the violence of the shipyard were targeted.

Ultimately, almost 8,000 workers were expelled from their jobs. This in a city where in 1907, the dockers, under the leadership of James Larkin, had put aside sectarian division and stood together and fought for Union recognition. Even as recently as 1919 there had been a level of solidarity among the workers during the Belfast Engineering Strike which helped secure a shorter working week. However, as Padraig Yeates notes among those who were prominent in leading the 1919 strike, such as the Catholic, Charles McKay, the chairman of the strike committee, and James Baird, a syndicalist, were among the thousands of workers expelled from the shipyards.

In response to the expulsion of the workers, who were now left without a wage, a relief fund was set up in August of 1920. Soon there were over 8,000 workers registered for the relief scheme which supported them and their families meaning in all over 23,000 people were dependent on the relief scheme for their daily survival. This situation became even more perilous as the violence continued into the autumn of 1920. As Mícheál MacDonncha writes,

In East Belfast where many Catholic-owned public houses and ‘spirit groceries’ (grocery shops with alcohol licenses) were attacked and looted and the families who lived over them forced out. One estimate said that over 70 such premises were looted and destroyed. The Catholic St. Matthew’s Chapel and nearby convent in Short Strand were attacked and burned. Catholic families were expelled from their homes in Bombay Street between the Falls and Shankill Road

In addition to thousands of men and women being expelled from their jobs the next two years would see close to 500 people lose their lives in political and sectarian violence in the city. Some historians have referred to the events of the period as the “Belfast Progrom”. This violent and uncertain time may be a decidedly inopportune time to start a new football league but that is precisely what happened. As Chris Donnelly has written, the Falls and District League was established to compete in the 1920-21 season, with local businessman John Kennedy a key driver in getting the league established, later becoming its President.

Football was not immune from the social upheaval taking place and there had been several instances of serious violence at games in the previous two years. While this was certainly not confined to Belfast the most prominent incidents had involved Belfast Celtic, the club in the city most closely associated with the Catholic and Nationalist population. The 1920 Irish Cup had been awarded to Dublin side Shelbourne without a final being played after the semi-final between Belfast Celtic and Glentoran, played in March of that year, had to be abandoned amid pitch invasions and revolver fire. Belfast Celtic, league Champions in the 1919-20 season would withdraw from the Irish League and not return until the 1924-25 season.

Several of the former Belfast Celtic players found their way into the line-ups of the Falls & District League teams which soon sought to align itself with the break-away Football Association of Ireland, formed after a split between Dublin and the IFA in Belfast. There were some historic tensions between Dublin and Belfast over issues like player selection as well as choice of venue for international matches and cup games, however, things came to a head in 1921 against the backdrop of the increasing violence of the War of Independence and the sectarian and industrial unrest in Belfast.

The IFA made the decision to move Junior and Intermediate Cup matches which had been scheduled for Dublin to Belfast, while there was something approaching a diplomatic incident at an amateur international between Ireland and France in Paris in February, 1921. The Irish team, which included players from Bohemians, Dublin United and St. James’s Gate in the starting eleven was greeted by a “Sinn Féin flag”, in actuality an Irish tricolour, in Paris by a number of the crowd. These later were reported to be students from Egypt who identified or sympathised with the Irish struggle for independence. In reality, there was only one Egyptian student among their number, Ibrahim Rashid, who had previously attended University College Dublin. The others involved in the protest were members of the Irish Student Association of Paris and included Roy C. Geary, a UCD graduate then studying in the Sorbonne, who would later become the founder of both the Central Statistics Office and the Economic and Social Research Institute, A.J. Leventhal (a Trinity graduate and friend of James Joyce) and man named Patrick Gallagher who later became a Professor of Chemistry in UCD. The identities of those involved were only disclosed by a letter from Roy Geary to the Irish Times in January 1982, more than 60 years after the event.

The final straw arrived in March 1921 when the venue for a replay of the drawn Cup game between Glenavon and Shelbourne came to be decided. The original match had taken place in Belfast so custom would suggest that the replay should take place in Dublin. However, the IFA ruled that the replay should also take place in Belfast. The FAI was founded a few months later in September and it was to this organisation that the teams of the Falls and District League chose to affiliate.

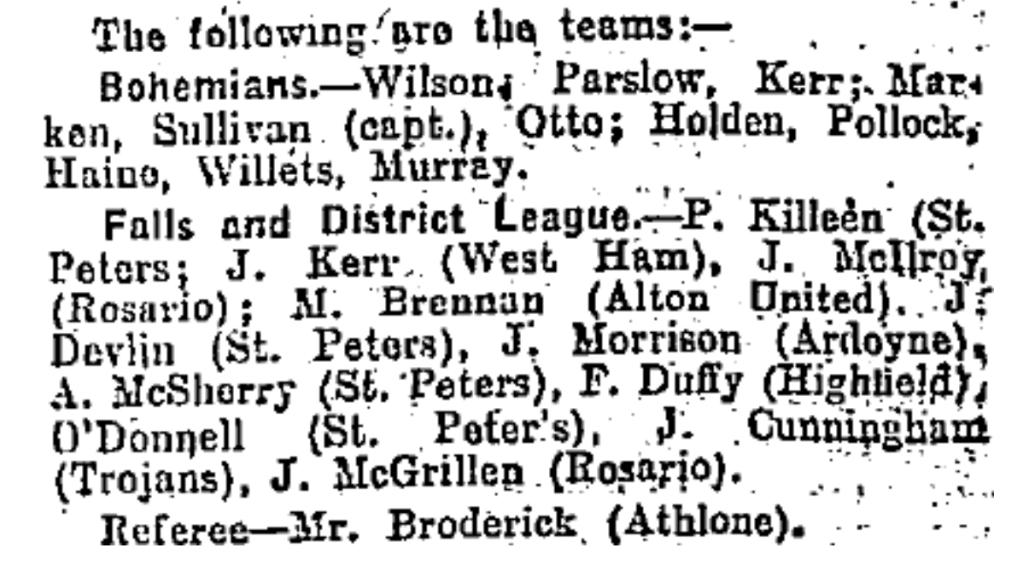

By September 1921, as the FAI was in the process of establishing itself as a separate entity and arranging its first competitions, the Falls and District League were coming to Dublin to take on Bohemians in a fundraising match for the expelled workers of Belfast. The match, set for Saturday, 10th September was to be the curtain raiser of the new season for Bohemians. Both they, and Shelbourne had withdrawn from the Irish League after the end of the 1919-20 season and they were preparing for the first season of the League of Ireland, due to kick off the following week. Bohs would finish second that season behind St. James’s Gate, and possessed a strong squad which included Billy Otto, the South African half-back, English winger Harry Willetts, Johnny Murray, Bert Kerr, Edward Pollock and amateur international striker Frank Haine as well as future Irish international Jack McCarthy.

The Falls team were made up of players from several member clubs, St. Peter’s, Alton United, Ardoyne, Rosario, Trojans, Highfield and West Ham. In fact, West Ham, a team made up mostly of expelled workers from the Belfast shipyards won a regional Belfast qualifying competition and as a result were drawn in the first round proper of the inaugural FAI Cup against Dublin side Shelbourne, who they took to a replay. Shelbourne triumphed in the replay but it was not the last significant impact that a Belfast side would have on the FAI Cup. According to one report from the Evening Herald Johnny McIlroy of Rosario and Joe Devlin of St. Peter’s were both former Belfast Celtic players. While it seems that Andy McSherry had also been on their books some years earlier.

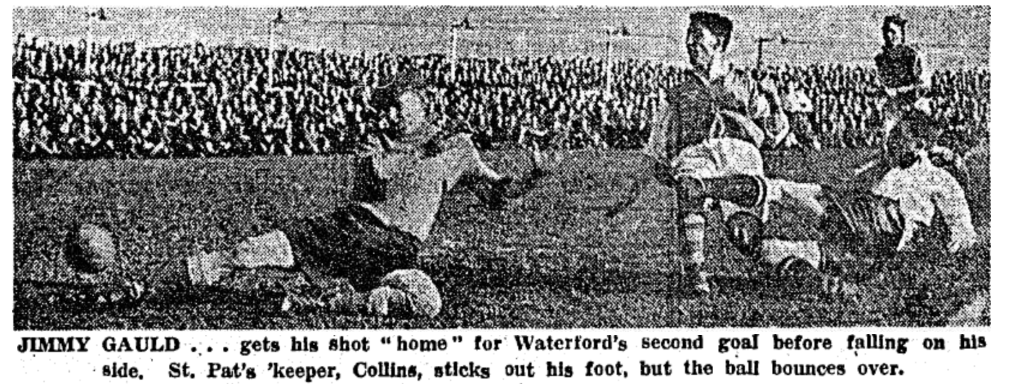

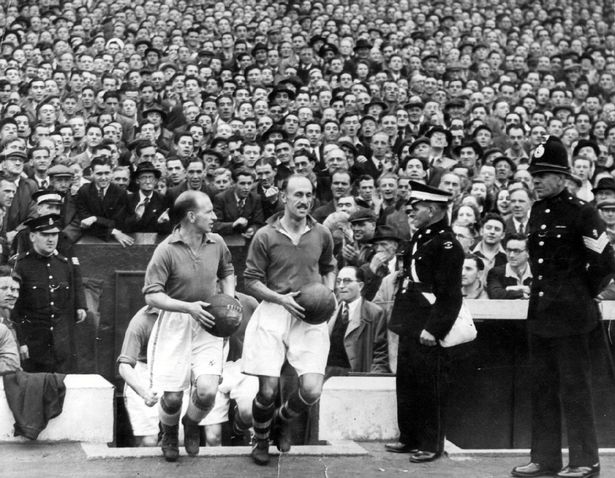

There was significant interest in the Bohemians v Falls XI game in Dalymount and a large crowd of around 6,000 attended and significant sums, estimated at £130, were raised for the expelled workers fund. The Herald further reported that “a novelty was occasioned by the policing of the ground by the IRA which proved most satisfactory”, specifically the Military Pension files of Michael Murphy show that this work was done by “C” company of the 3rd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA. The reports describe a lively, entertaining, and competitive match. The Falls took the lead after around 15 minutes when O’Donnell of the St. Peter’s club scored after good work from Duffy. Kerr came close to doubling their advantage soon afterwards. Bohs equalized before half-time through the quick-thinking of Harry Willetts whose parried shot was tapped in by Thomas Holden. In the second half Bohs began playing with the wind and began pressing for the winner, it eventually came through some excellent individual play on the part of Johnny Murray who curled a shot past Killeen in the Falls goal which secured a victory for Bohemians.

Afterwards dinner was served to both teams in the Dalymount Pavillion followed by a “smoking concert”. Such was the success of the match that it was agreed that a return game in Belfast in the very near future was desirable. Initially a return game for later that month was suggested, although this clashed with a League of Ireland fixture between Bohs and Jacobs. Eventually October 8th 1921 was agreed as a date for the return fixture in Belfast and the Falls League set about trying to secure Celtic Park, home ground to Belfast Celtic as a venue. This, however, couldn’t be arranged and the match was due to be held in Shaun’s Park, a former home to Belfast Celtic and later known as MacRory Park and in later years more associated as a site for GAA than soccer. As Chris Donnelly notes the venue also played host to an all-Ireland semi final in October 1909 between Antrim and Louth, in which the Wee County would run out winners by 2-13 to 0-15. During the mid-1930s, many Catholic families were forced to take shelter in the park after being burnt out of their homes in the sectarian riots that engulfed the city.

Along with the difficulty securing the ground there were also challenges to even secure a hotel or restaurant to host the visiting Bohemians team. In the end the Falls side had to host Bohs in their clubhouse and arrange their own catering. For Bohs part they seem to have made a day of it in relation to their journey north. Certainly, there was no mention of any concern for the safety of the travelling party. They stopped for lunch at Cushendall where there were speeches from the various members present, including club President Michael Moynihan, and secretary of the FAI Jack Ryder. While dining they also met with Clemens J. France, a lawyer from Seattle working in Ireland as part of the White Cross who were providing aid during the War of Independence. France would later become part of a committee chaired by Michael Collins that helped develop early drafts of the first Constitution of the Irish Free State.

Bohs leisurely journey continued with stops in Camlough, Co. Armagh where they were welcomed by the Parish Priest Father Kerr who described the group as “plucky” for venturing up north during the “days of trouble”, while there was a further stop in Larne before the eventual arrival in Belfast just before the curfew.

The return match itself was a significant draw, even hampered as the game was with having to use Shaun’s Park. The newspaper Sport claimed it was the biggest gate of the weekend, and would have undoubtably been even larger had Celtic Park been made available. That the match drew larger crowds than other games in Belfast that weekend, which included Linfield taking on Cliftonville and Glentoran hosting Distillery, was testament to the appeal of both Bohemians and the Falls selection. Estimates had the crowd at around 3,000 and the return from the gate at around £65. Roughly half and attendance and takings of the earlier Dalymount match.

The scoreline on the day was the reverse of the Dublin game, the Falls selection triumphing 2-1 this time. They were aided considerably by the return to the starting line-up of their centre-forward, Vincent Davey of the St. Matthew’s club. Davey scored both goals either side of Frank Haine netting for Bohs with Johnny Murray missing a great opportunity to equalise. Just a few weeks earlier Haine had scored the first goal ever in the League of Ireland as he helped Bohemians to a comfortable win over YMCA. Davey on the other hand had missed out on the trip to Dublin a few weeks earlier, his absence and his reputation noted by the media on that occasion. As well as being centre-forward for St. Matthew’s, Davey was also the Parish Priest of St. Matthew’s.

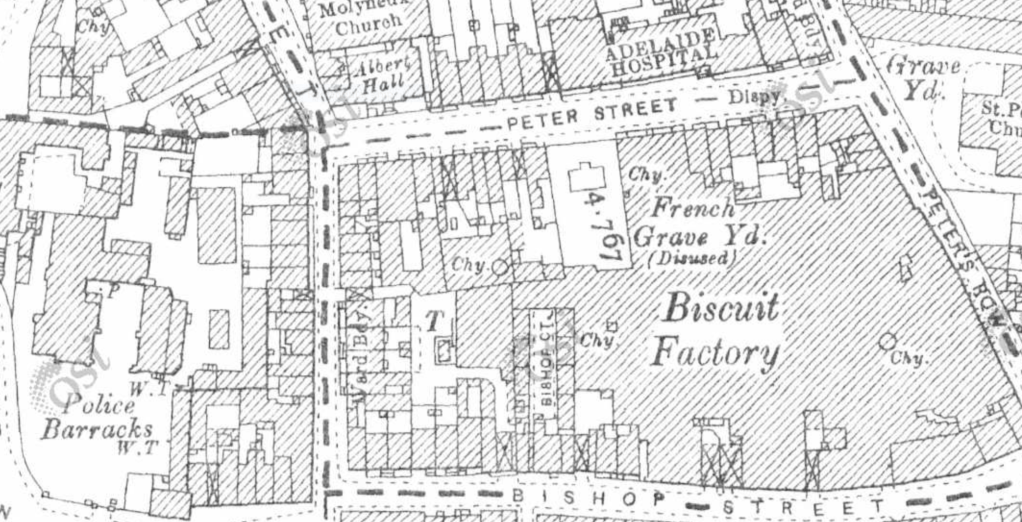

Located in the Short Strand area of Belfast, St. Matthew’s Church and the neighbouring convent had been attacked on successive nights on the 22nd and 23rd July as Loyalist gangs first began pelting the buildings with stones before then trying to set them ablaze. This was only prevented by a detachment of British troops opening fire on the attackers. Fr. Davey had also been involved in attempting to ease tensions at the time of the worker expulsions and sectarian violence.

In a somewhat bizarre connection a Church of Ireland Reverend and former British Army officer, Frederick Chesnutt-Chesney from the same area was also involved in leading civilian groups from his congregation to protect Catholics and try to stem the tide of violence in July and again later in the year after the killing of Oswald Swanzy by the IRA in Lisburn sparked a fresh wave of disorder. Chesnutt-Chesney had been a goalkeeper for Bohemians in the years prior to the First World War. In the small world of Belfast surely the two footballing clerics must have known each other?

Around the same time that his Church had been attacked Davey had intervened in a sectarian labour dispute. In response to the shipyard expulsions a small group sent a letter claiming to be from the IRA and threatened the management of the Anderson & Son felt and roofing works factory in Short Strand. They had demanded the dismissal of all Protestant workers from the factory. Fr. Davey as a local priest approached the factory’s Managing Director, a Mr. Brock to assure him that these demands were not representative of the community and we not made “by any responsible members of their flock”. Davey, some other Catholic clergy, and according to the Freeman’s Journal a group of IRA men acted as a picket to protect the Protestant workers at the factory as they left during their dinner hour. Davey would later work in the Catholic Missions in Nigeria before returning to Ireland and becoming the Parish Priest of the town of Antrim until his death in 1970. He maintained in interest in football and an affection for Killyleagh United F.C. from the town where he had been priest during the years of the First World War.

Bohemians returned to Dublin and to the League of Ireland, they would finish second in that inaugural season. Despite the limits placed on their hosts in terms of venue for both the game and a reception the Bohs players and administrators enjoyed themselves after the match and spoke “glowingly in praise of the hospitality of the northern adherents to the FAI”. The following year they bolstered their squad with the signing of Johnny McIlroy, the former Belfast Celtic star who had been lining out for the Falls League as a full-back when they came to Dalymount. McIlroy would have a long and successful career with Bohs, winning league titles in 1924 and 1928 and adding the 1928 FAI Cup to the Irish Cup he had won with Belfast Celtic ten years earlier.

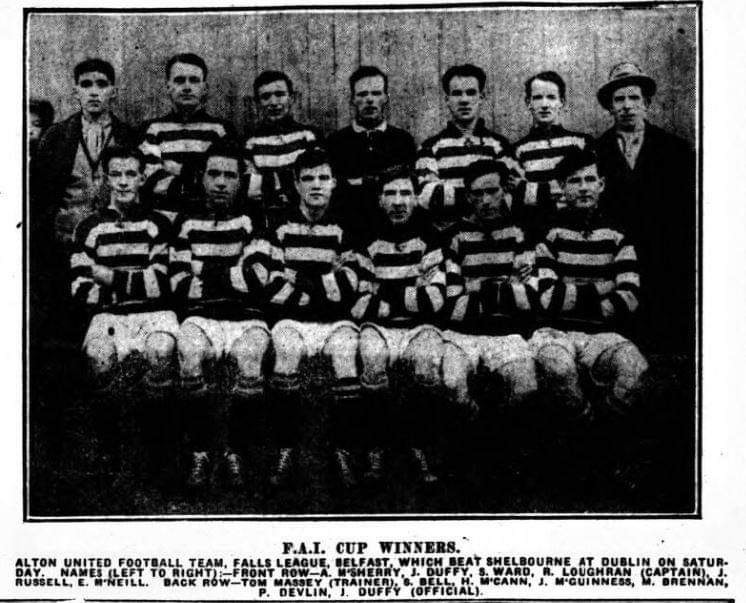

For the Falls League things remained challenging. A cup competition, entitled the Expelled Workers Cup was created to help raise money and keep the workers active. The teams of the Falls league competed in it. In 1922 this cup was won by the Ardoyne club while West Ham, the side who had taken Shelbourne to replay in the FAI Cup, won the Falls and District League. While they had nearly caused a cup upset, their Falls League counterparts, Alton United, created a downright shock – they would win the 1923 FAI Cup final against Shelbourne.

Alton had some pedigree, previously known just as “United” they had been IFA Junior Cup champions in 1920, when they began operating from rooms above the Alton Bar they changed their name to Alton United. Alton were based in Carrick Hill, a small Catholic enclave at the bottom of Belfast’s fiercely loyalist Shankill Road area and surprised all of Ireland when they defeated Cork side Fordsons in the semi-final and then beat clear favourites Shelbourne 1-0 in the final, with Andy McSherry grabbing the winning goal. On that Alton team was Michael Brennan, who had played centre-half as the only Alton player in the Falls XI which visited Dalymount in September 1921. In another echo of that match the security for the Alton side on their visit to Dublin were, according to some reports members of the IRA. This was likely a mistake and actually referred to the Free State Army as just days earlier Liam Lynch had issued the “Amusements Order” which called for all sports and amusements to be cancelled and called for a period of national mourning for the members of the IRA executed by the Free State Government. This was in March 1923, two months before the “dump arms” notice led to the end of the Irish Civil War.

Michael Brennan, the star centre-half for Alton United and the Falls League XI is an interesting character and his story gives a glimpse into the complexity of life in Belfast at the time. From the research carried out by family members Siobhán Deane and Damien Brannigan we learn that Brennan was a WWI veteran, having heeded the call of John Redmond to join the Irish Volunteers and subsequently the British Army where he served with the 6th Connaught Rangers for whom he was regiment boxing champion as well as playing football for the regiment. He was from Alton Street in Belfast and was a shop owner in the city after being demobbed in 1919. His business was one of those destroyed during the violence of the 1920-22 period while his older brother Bernard (Barney) was seriously injured after being shot in the Carrick Hill area of the city. Both Michael and his brother Robert had fought in World War I and both played for Alton United after their return home. Robert would later become involved with the Belfast Brigade of the IRA and his home was used as a safe house. Michael would remain in Belfast and remain involved with Alton United for many years after hanging up his boots being at various points club chairman as well as club treasurer.

The Alton United win, which might have become a significant landmark to progress for Belfast clubs affiliated to the FAI became something of a coda. By the end of 1923 the FAI had affiliated to FIFA and also met with the IFA and the Football Associations of England, Scotland and Wales in Liverpool at a conference designed to heal relations after the split two years previously. Part of this rift-healing meant that the FAI agreed to confine its jurisdiction to the twenty-six counties. One gesture towards a healing of old animosities was an early cross-border competition – the Condor Cup – a two-legged annual affair contested between Bohemians and Linfield. Aside from such cross border cups there would be end to any Northern sides involvement in FAI domestic league and cup competitions until the affiliation of Derry City in 1985. Today, it is fair to say, the Falls league and it’s member clubs are mostly forgotten, even in their home city. Belfast Celtic returned to the Irish League in the 1924-25 season and once again became the footballing focus for much of the city’s Nationalist community until their eventual, complete and final withdrawal from football in 1949.

The expelled workers relief fund continued to support thousands of workers and their families in Belfast, in some cases the burden was even greater than the mere loss of employment as hundreds of predominantly Catholic occupied homes had also been burnt down. Fundraising continued, apart from the games involving Bohemians to raise funds, Shelbourne also made financial donations to support the workers, while in July 1922, some two years after the original shipyard expulsions, there was even an “Italian Operatic concert” under the management of Enrico Gagni, held to raise funds in Dublin’s Theatre Royal.

While the immediate post-War years had seen a boom in Belfast’s shipyards with a huge demand for new shipping to replace the vessels lost in the First World War, the worker expulsions had a damaging impact. Many of the workers expelled has specialist skills that were not easy to replace, they had also gotten rid of some of their strongest, most formidable Trade Union representatives. This coupled with the collapse in global demand by the end of the decade caused by the stock market crash of 1929 meant that Belfast’s shipyards and engineering industries had taken blows from which they wouldn’t recover.

The 1920s were a challenging decade from a sporting point of view for the FAI, they had to battle for international recognition and even domestic credibility. There was real concern that directly after the split that clubs like Bohemians and Shelbourne would want to remain part of the Irish League rather than throw their lot in with the FAI, while it was clear that Belfast clubs like Linfield or Glentoran would never leave the IFA and that the crowds generated by the visits of these clubs as well as international matches in the Home Nations Championship were also lost. Despite being an amateur club the 20s were to be a time of relative success for Bohemians, a league title was secured in 1924 while the 1927-28 season saw Bohs make a “clean sweep” of the League, FAI Cup, Shield and Leinster Senior Cup. This decade also saw Dalymount become the venue of choice for international matches as well as cup finals and prestige friendlies.

The joining of FIFA in 1923 and the Liverpool conference with the other UK associations put an end to any claims of jurisdiction by the FAI over northern clubs, by the 1950s the habit of the IFA and FAI selecting the same players for international games had also come to an end. Cross border tournaments with a variety of sponsorship titles, came and went but the distance between Belfast and Dublin grew in footballing terms. The split which in the 1920s had seemed temporary and resolvable, hardened. It is worth remembering that at a time of crisis Bohemians (and indeed Shelbourne) were there to support the footballers and the workers of Belfast.

With a special thank you to Manus O’Riordan for his assistance in researching this article.