From Brezhnev to Aleinikov – A Season of Seasons

Guest post by Fergus Dowd

At 11:00 am on November 11th, 1982, news anchor Igor Krilliov looked into the camera and announced the death of Leonid Brezhnev with tears in his eyes. The fifth leader of the Soviet Union had passed away the day before; the delayed announcement was seen as an ongoing power struggle to see who the new General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would be.

Seven hundred and twelve kilometres from Moscow in the city of Minsk, Sergei Aleinikov sat watching Krilliov’s words in disbelief. Russia had annexed the city on the banks of the Svislac in 1793 because of the Second Partition of Poland; factional differences in the country had led to civil war with the surrounding powers of Prussia and Austria also taking Polish lands. By 1939 close to half a million people lived in Minsk; that was all to change on the 24th of June 1941 with the Minsk Blitz during World War II. As three waves of Luftwaffe bombers, forty-seven aircrafts each leveled the city of Minsk, a poorly organised Soviet anti-aircraft defence watched on as the water supply was destroyed. This led to most of the city’s buildings and infrastructure being destroyed and local dwellers evacuating. More than forty years later, as the death of Brezhnev kick-started the demise of modern Soviet communism and five days of mourning were announced, Sergei Aleinikov put his dreams of Dynamo Minsk conquering the World of football in the Soviet Union on hold.

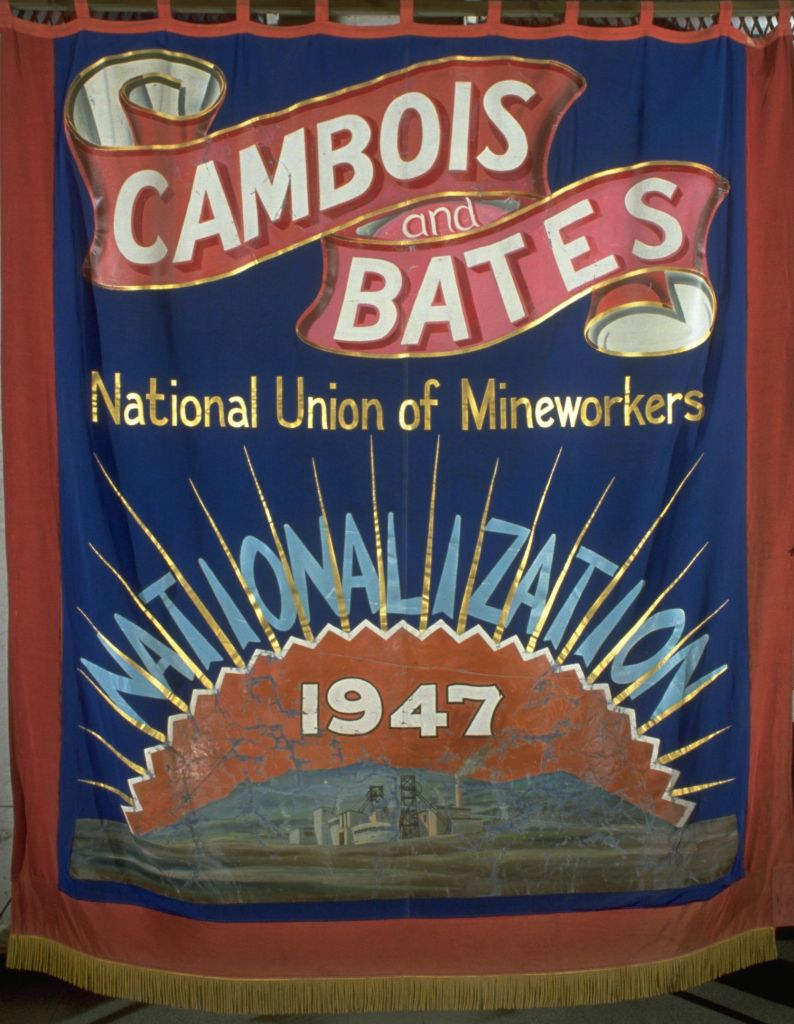

The ‘Dinamo’ Society, founded in April 1923, was the brainchild of Bolshevik revolutionist Felix Dzerzhinsky known as ‘Iron Felix,’ under the sponsorship of the State Political Directorate (GPU) and the Soviet political police group of the NKVP. Football and the society would arrive in Minsk in 1927 with the formation of ‘Dinamo Minsk.’ Felix, who was head of the first Soviet secret police organisation, would never see the fruits of his labour in the city as he collapsed and died during a debate at a Central Commission session a year earlier.

On the 18th of June 1927, Dinamo Minsk played their first game against Dinamo Smolensk; after the Russian revolution of 1917, which ended the Romanov dynasty and centuries of Russian Imperial rule, Smolensk became part of the Belarussian SSR. Minsk ran out 2-1 winners on the day. The club played in the official Belarussian SSR league; in their debut season, the team from the Belarussian capital would become champions. In winning the league, Minsk had dethroned FC Belshina Bobruisk, who had won the unofficial league the previous year; the city to the East of Belarus was a battlefield for waring factions of Poles and Russians during the October revolution of 1917. The ‘Tomb of the Unknown Soldier,’ which stands in Warsaw, commemorates those who perished in the Battle of Bobruisk.

Through their league victory, Minsk qualified for the ‘Season’s Cup,’ which took place between the Republic’s league champions and cup winners, Belarus’ answer to England’s charity shield. In 1936 the first foreign team would play on Belarussian soil as Dinamo would face off against the Spanish National team dubbed the ‘Fascists versus the Fighters’ – Spain would run out 6-1 victors at the Minsk Tractor venue. It would take Dinamo Minsk a decade to break into the ‘All Union’ Soviet pyramid of football representing the Belarussian League in 1937 in the ‘Team of Masters.’ Minsk would face off against the powerhouses of Dynamo and Spartak Moscow, the latter including the great Leonid Rumyantsev, who had been a joint top scorer in the Russian league that season.

Rumyantsev would be one of the Soviet’s greatest pre-war strikers, winning the local league three times while coming close to winning the USSR championship twice winning two bronze medals. Minsk would lose out to Dinamo Tbilisi, led by Hungarian coach Jules Limbeck, who led Galatasaray to the Istanbul League in season 1930/31. The dreams of the Belarussian champions were ruined by Boris Paichadze, the Georgian goal machine who scored 111 goals in 195 appearances for the club. Although he would guest in Romania during the second world war and become known as the ‘Caruso of Football,’ his genius was seen in line with the great Italian tenor. It would take Dinamo Minsk a further three years to get to the top table of Russian football again. That year of 1940, as Europe was destined for unrest, Dinamo Moscow would conquer all; that great team included Sergei Aleksandrovich Solovyov, a dual footballer and ice hockey player. Moscow would tour the UK after the war playing Chelsea in their first game on British soil at Stamford Bridge; 75,000 would watch the first football match after the war as touts sold 10shilling tickets for £4.

World War Two would mean football was put to one side as Minsk started to put together a great side, including Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Sevidov, who would manage the club in the 1960s Latvian Eriks Raisters who had come to the club after winning three local championships. Raisters, like so many, would perish on the front line during the second world war dying on May 25th, 1942. Dinamo Minsk’s rise in Belarussian football had seen them promoted to the Soviet Top League. However, the war meant they only played seven games before football was cancelled.

Following World War II, the city’s destruction meant the new Dinamo Stadium was constructed. It included a specially created box in the centre of the stadium for the head of the KGB, Lawrence Fomich Tsavana, who decided which government members could attend games and the bonuses for players. For the first five seasons, the team finished in the bottom three of the league; by 1950, the club was relegated to the second tier of Soviet football but would bounce back immediately. By 1954 Dinamo had become Spartak and finished third in the Soviet top tier, the team receiving bronze medals; in the side was the great Russian goalkeeper Aleksey Khomich.

Khomich had starred for Dinamo Moscow on their tour of Britain, his outstanding bravery in goal giving him the nickname of ‘the Tiger’; he had joined Minsk in 1953. The netminder would mentor the great Lev Yashin and become a sports photographer after retirement working with the first sports newspaper in the USSR, Sovetsy Sport. By 1960 the club became Belarus Minsk cementing their place as the top team in Belarus. It was short-lived Minsk would find themselves in Subgroup 2 of the Soviet top league finishing sixth but would face elimination in round two as the league continued to grow. Under the guidance of Sevidov, who had played in the Team of Masters in 1940, the club who by then had reverted to ‘Dinamo’ finished third in the league and won the cup in 1965. One of Sevidov’s key players was number seven Leonard Adamov, a diminutive burly fair-haired winger who was nicknamed the ‘little napoleon’ he moved with grace across the pitches of the USSR. Adamov would be awarded a Diploma from the Supreme Council of Belarus for his work and dedication to sports development. He would become Dinamo Minsk’s assistant coach between 1974 and 1977, but his life would end in tragedy. Adamov would commit suicide jumping out of the window of his 8th-floor apartment in Lenninsky Prospekt in the centre of Minsk on November 9th, 1977.

More than five years after the death of Adamov, Sergei Aleinikov and his Dinamo Minsk teammates were on the cusp of greatness; two days before Brezhnev’s death, Minsk had been held at home to FC Pakhtakor Tashkent of Uzbekistan in round 34 of the Vysshaya Liga. It had all started in the sunshine with a home 3-2 victory against the Georgians of FC Torpedo Kutaisi. Now all roads would lead to Moscow with two away games against Dinamo Moscow and Spartak, powerhouses of Russian football. On November 15th Leonid Brezhnev’s coffin was borne upon a gun carriage led into the heart of Red Square; he was buried in front of the Kremlin Wall with a state funeral, the pomp, and ceremony not seen since the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. Two workmen wearing red armbands lowered Mr. Brezhnev’s coffin into the grave at 12:45 p.m. while across the country in thirty-six cities for five minutes, everything stopped; from Leningrad to Minsk, everything was silent in the factories and on the farms in remembrance.

The following day, Dinamo Minsk headed for the capital to play Dinamo Moscow in their penultimate game, coached by Eduard Malofeyev, part of the cup-winning team of 1965, and won a bronze medal in 1963 with the club.

Malofeyev was a doctor of football, a man who brought swashbuckling attacking football to the city of Minsk in what he called ‘sincere football.’ He had played in the World Cup in England in 1966, announcing himself to the World with a brace against North Korea at Ayresome Park, Middlesboro, in the USSR’s first game. Malofeyev’s team talks were legendary; they could last up to three hours. No player was spared; he made the team of Aleynikov, Gotsmanov, Prokopenko, Vasilevskiy, and netminder Vergeyenko feel ten feet tall. The day after Brezhnev was laid to rest in their penultimate game, Malofeyev’s Minsk routed Moscow 7-0; that season Igor Gurinovich and Georgi Kondratyev netted twenty-three times between them.Kondratyev would manage Minsk in a caretaker capacity in the early noughties and the Belarus national team between 2011 and 2014.

The convincing victory meant a win against Spartak Moscow would see Dinamo Minsk crowned champions. Spartak was still reeling from the ‘Luzhniki disaster’ where sixty-six people had died during a stampede at the Grand Sports Arena at the Central Lenin Stadium in a UEFA Cup tie against HFC Haarlem of the Netherlands. The disaster occurred on Oct 20th, nearly a month before the game with Minsk, as fans converged on Stairway One in the East Stand of the ground with minutes remaining in the European tie. As snow filled the night sky all around Moscow, fans headed for the exit closest to the local Metro Station, only for tragedy to occur leading to the USSR’s worst-ever sporting disaster.

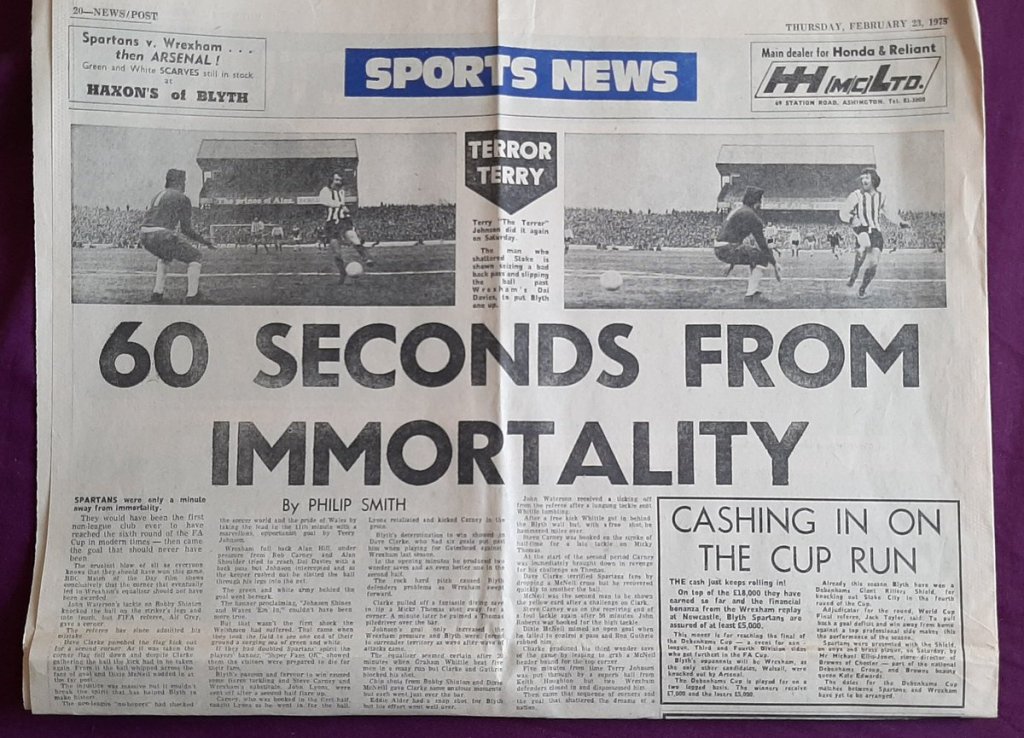

On November 19th, as the final round of games were played out, Dinamo Kyiv was on the coat-tails of Malofeyev’s men. A draw would mean a play-off against the team from the Ukraine, and a loss would see Kyiv crowned champions if they beat Ararat Yerevan. Valeriy Lobanovsky led Kyiv, a polar opposite of Malofeyev; he introduced computer technology turning football into a science; the modern-day stats men would be proud. In his pre-match speech, Malofeyev talked about monkeys and lions and how the lions might eat the monkeys to death, or one monkey might sacrifice himself for the team. In essence, what Malofeyev meant was that team would have to sacrifice themselves for victory. The speech did not exactly have the immediate effect as Spartak opened the scoring after seventeen minutes. Still, a brace by Ivan Gurinovich before halftime saw Dinamo Minsk go into the break 2-1 up.

In the second half, the Belarussians started like a house on fire goals from Petr Vasilevsky and Aleinikov; after twelve minutes of the second half, saw Minsk coasting 4-1. Two goals, though, by the home team meant the last few minutes felt like an eternity, but at 8:47 on the night of Nov 19th, 1982, ‘Dinamo Minsk were champions’. The team would return to a heroes welcome with thousands welcoming them off the train from Moscow; Malofeyev would go on to manage the USSR national team heping his nation qualify for Mexico 1986, but fired before the championships started.

For Sergei Aleinikov, he would play in the European Cup of 1983/84 with Minsk reaching the quarterfinals, narrowly losing to Dinamo Bucharest two to one on aggregate; Liverpool would defeat Roma in the final that year.

Aleinikov was known for his stamina, tactical nous, and passing ability. A centre-half in the Alan Hansen mould, he would eventually leave eastern Europe for Turin and the black and white of Juventus. In 2003 Sergei was voted the most outstanding Belarussian footballer in the last fifty years. The walls of communism have come tumbling down.

Belarus is now an independent state, but in Minsk, they still talk about 1982, and the team that toppled all in the old USSR.