Bohs in Europe – the 1970s (Part I)

The 1970s saw Bohs first forays into European competition. The decision taken in 1969 to abandon the strict amateur ethos of the club, observed since its foundation in 1890 paid immediate dividends with victory in the 1970 FAI Cup and secured entry to the 1970-71 European Cup Winners Cup. Given the club’s name it was somehow appropriate that our first opposition should come from what is now the Czech Republic. Over the course of the decade Bohs would qualify for European competition eight times, and would see the club enjoy its first victories. The focus of these articles are the dramatic campaigns of 1977-78 in the UEFA Cup and the 1978-79 European Cup.

The 1976-77 League season had seen Bohs finish second, a point behind Sligo Rovers who won just their second ever title. It was a young, talented Bohs side, packed with players who would go on to have successful international careers, and some who had already been capped by their country. That second-place finish secured qualification for the following season’s UEFA Cup, now rebranded as the Europa League. European football in the 1970s was quite a different place from today, the splintering of the USSR and Yugoslavia into their constituent parts was still decades away and nations like the Faroe Islands or Andorra were not yet represented in European competition. With a smaller number of nations there was no qualifying round and no group stages, qualifying meant entry into a straight knock-out, first round tie and a potential draw against a European heavyweight.

There was the dilemma here for Irish clubs, whether to hope for a smaller, more obscure team, and a better opportunity to progress, or the desire for a big name in the draw and a potential bumper home gate. It’s worth noting that in this era Europe was generally a drain on club resources, prize money was not nearly as significant to an Irish club as it is today and getting drawn against a little-known side from Eastern Europe could end up being hugely costly to a club’s finances. The biggest draws for an Irish club, then as now, were British clubs, well known to the Irish public and almost guaranteed to draw a big crowd even if the chances for progression were slim.

It was against this backdrop that Bohemians were drawn against Newcastle United in the opening round of the 1977-78 UEFA Cup, with the first leg being a home-tie in Dalymount. From a Bohs point of view this had the potential to be a lucrative tie, Newcastle had finished fifth in the First Division the previous year and would be well known to a Dublin audience, while the away trip to Newcastle could be done at relatively low cost. Billy Young, the long-serving Bohs manager during this period recalled that the club made all their travel arrangements through a travel agent named “Mrs. Chisholm” and while she couldn’t always arrange the most direct route, she always arranged the cheapest! For Bohs away trip this would entail a flight to Leeds, and after some delays, a coach to Newcastle.

The Bohs squad for those games against Newcastle was one of the strongest of the decade, in goal was Mick Smyth, the veteran of the team at 37, he was hugely experienced and successful, having starred for Drumcondra and Shamrock Rovers before joining Bohs, he’d also been capped for Ireland against Poland back in 1968. In front of Smyth were the likes of full-back Eamonn Gregg, who would win eight international caps during his time as a Bohs player, and later manage the club, Tommy Kelly, another vastly experienced player who still holds the club record for most appearances for Bohemians, on the left of defence was Fran O’Brien, a pacey, attacking player from a footballing family, he would win three caps for Ireland and ended up spending the majority of his career playing professionally in the United States. These were supported by the likes of the imposing Joe Burke, and classy defender/midfielder John McCormack, inevitably nicknamed “The Count”.

The Bohs midfield set up might strike current fans as familiar, there was a focus on using the flanks as avenues of attack, helped by the fact that in the shape of Gerry Ryan and Pat Byrne they had two of the best wide men in the League. Both players would win numerous caps for Ireland, Ryan would later star for Derby County and Brighton while Byrne enjoyed spells with the likes of Hearts and Leicester City, but is probably best known for his time with Shamrock Rovers (boo!). Up front was the peerless Turlough O’Connor, another Irish international, he would set goalscoring records for Bohs not broken until the time of Glen Crowe, and would finish the 1977-78 season as the league’s top goalscorer. Turlough would later succeed his erstwhile teammate Eamonn Gregg as Bohs manager in 1993.

This group was ably assisted by players of the quality of Padraic O’Connor (brother of Turlough), Tony Dixon, Eddie Byrne, Niall Shelly and Austin Brady. As mentioned, the side was coached by Billy Young, a stalwart player for Bohs during the club’s amateur era in the 1960s. Young would take the managerial reigns at Dalymount in 1973 and stayed in charge through to 1989!

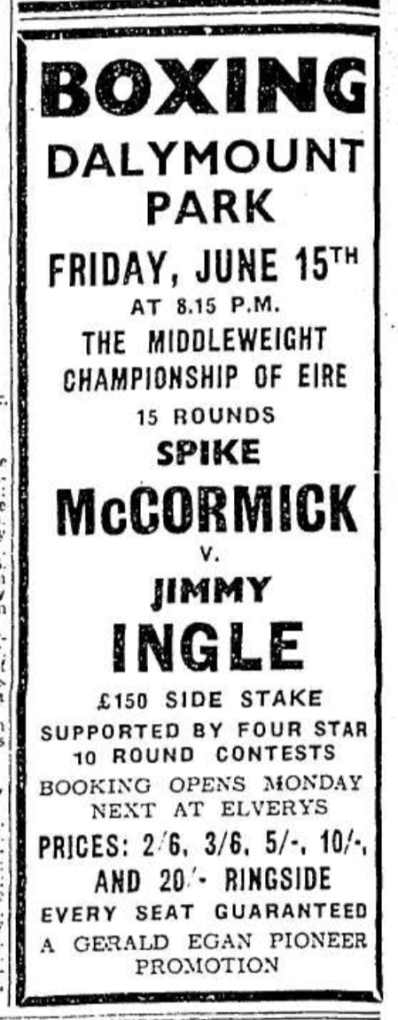

To ensure a bumper crowd for the Newcastle match the Bohemians committee decided to reduce the standard entry fee for the game, the Irish Independent reporter Noel Dunne went so far as to say that Bohs were offering the cheapest football in Europe with fees ranging from £2 for a stand ticket down to 50p for a spot on the terraces. The pulling power of an English team and cheap tickets had the desired effect and Dalymount welcomed almost 25,000 spectators for the home leg. Bohs were able to field an almost full strength side apart from Joe Burke who missed out having scalded his foot in a workplace accident (not something that the opposition side would likely have had to deal with). The Bohs XI were Mick Smyth, Eamonn Gregg, Fran O’Brien, Tommy Kelly, John McCormack, Padraic O’Connor, Pat Byrne, Niall Shelly, Turlough O’Connor, Eddie Byrne and Gerry Ryan.

Ryan especially was a thorn in the side of Newcastle, going close early on with a long-range shot, and helping create the best chances for the game for Bohemians thanks to his excellent link-up play with Pat Byrne and Turlough O’Connor. While Bohs had enjoyed some decent opportunities in the first half Mick Smyth was called into action to make crucial saves from Micky Burns and it took a last-ditch Eamonn Gregg clearance to deny Irving Nattrass. However, the performance was about to become of secondary importance in proceedings. With the sides still at 0-0 at the break, trouble began to flare when the Newcastle players returned to the pitch for the second half.

With Newcastle keeper Mike Mahoney taking up his position in goal in front of the school end of the ground there was a barrage of missiles and he was struck in the head by a beer can and play was suspended so that Mahoney could receive treatment. But that was just the beginning. Trouble began to flare between Bohs supporters in the tramway end and Newcastle fans in the main stand, chants, provocation and missiles flew back and forth. The Newcastle Chronicle reporter John Gibson claimed that the spark had been the unfurling of a Union Flag by some Newcastle fans which was met with anti-British chanting by the home fans, followed by fans hurling more than insults. With only fourteen minutes of the second half played the referee withdrew the players to the relative safety of the dressing rooms. In the interim additional Gardaí had arrived at the ground and there were baton charges to restore order. Post-match reports stated that a Garda and several others were injured and that five arrests were made at the game.

After some semblance of order had been restored the players returned to the pitch to complete the game with the crowd of almost 25,000 in what was described as a somewhat “unreal” atmosphere. The reports of the actual football, and conversations with both Billy Young and Tommy Kelly who were involved in the game, as Bohs manager and player respectively, recall a competitive game full of good football. Kelly remarked on the quality of player that Newcastle had, like Alan Kennedy who would achieve fame as a European Cup winner with Liverpool, Northern Irish international David Craig, and his Scottish namesake Tommy Craig. Indeed, Bohs had a great opportunity to win the game with twelve minutes remaining only for Mahoney (now patched up) saving after an excellent Bohs move put Turlough through on goal.

As was often the case with League of Ireland sides in Europe a decent home result and performance wasn’t enough to get Bohs through the tie. A flight to Leeds and a delay in getting the coach to Newcastle meant that the Bohs side arrived late in the Evening before the away leg, not ideal preparation. The coach had also stopped to collect the Derby County manager Tommy Docherty who had also attended the game in Dalymount. Docherty was a larger than life character, and hugely popular within the game, he had won the FA Cup a year earlier with Manchester United but had been sacked after beginning a relationship with Mary Brown, the wife of club physio Laurie Brown. Docherty was keen on signing two of Bohemians’ outstanding players, left-back Fran O’Brien and winger Gerry Ryan. Both players were in demand and indeed Newcastle had made offers for both players around this time.

Aware that there was competition for the players’ signatures Docherty was adding a personal touch. He was well-known to the Bohs committee, during his time with Manchester United he had signed the likes of Gerry Daly, Mick Martin and Ashley Grimes from the club, and was keen to make some key additions now that he found himself managing at the Baseball Ground. After the home leg in Dalymount, he had asked Billy Young if he could buy the players a drink, Young agreed and Docherty proceeded to order bottles of champagne for the Bohs players, before catching a private flight back to Derby.

The away leg was to be a let-down for Bohs, though Tommy Kelly remarked that the squad travelled with a certain level of confidence, feeling unlucky not to have won the first leg, the Magpies were a different prospect on home turf. They also welcomed back Alan Gowling to the starting eleven and he and Tommy Craig proved the match-winners, both scoring a brace to hand the Geordies a 4-0 win on aggregate. Within two days of the away leg newspapers were announcing that Derby County had signed Gerry Ryan and Fran O’Brien for a combined fee of £75,000 (£40,000 for Ryan and £35,000 for O’Brien), and that the players would merely be flying back to Dublin to collect belongings before moving to their new club. Speaking to Fran O’Brien he claimed the fact that Derby was close to Nottingham, home to his brother Ray who was playing for Notts County, influenced his preference in choosing Derby over the Magpies.

However, a supposed issue with O’Brien’s medical halted the move though what the issue was wasn’t made clear to O’Brien or Bohemians. Whatever the concerns from the Derby medical, Fran O’Brien would enjoy a long and successful career. He joined the Philadelphia Fury in the NASL a year later and played alongside the likes of Alan Ball, John Giles and Peter Osgood, he also became the first player to be capped for Ireland while playing in the United States.

Ryan would only spend a year at Derby before falling out with Docherty and moving to Brighton for a fee of £80,000, double what Bohs had been paid for his services a year earlier. He was to become a fan favourite at Brighton and joined a significant contingent of Irish internationals there including Tony Grealish, Michael Robinson and Mark Lawrenson. He was kept out of the starting XI for the 1983 FA Cup Final by fellow Dubliner and future Shels player Gary Howlett. Ryan would go on to win eighteen caps for Ireland before an injury aged 29 effectively ended his career.

In the UEFA Cup Newcastle would lose their next tie 5-2 on aggregate to Corsican side Bastia, a masterclass by Dutchman Johnny Rep in St. James Park where he scored twice in a 3-1 sealed the Magpies fate in the competition. A week later their manager Richard Dinnis, a man promoted from his role as coach to manager at the insistence of a sizeable proportion of the Newcastle squad, was sacked. The former Wolves manager Bill McGarry was eventually appointed in his place but he couldn’t save Newcastle from finishing second bottom and being relegated. Dinnis would later end up as coach with Philadelphia Fury where he would manage Fran O’Brien, the player he had just previously tried to sign from Bohemians.

As for Bohemians, the season couldn’t have finished more differently to their Geordie opponents, they would finish top of the sixteen team League of Ireland, pipping Finn Harps to the title and seeing Turlough O’Connor as the League’s top goalscorer. Victory also secured entry to the following season’s European Cup, however the crowd trouble at the Newcastle game cast a long shadow and would have consequences for the club.

Tommy Kelly had described the trouble are less violent than that which had accompanied the game against Rangers in 1975, and Billy Young also said that the Bohs’ predicament could have been worse were it not for the intervention of Paddy Daly who had been looking after the UEFA observer at the game. Sensing the tension in the air at the game he ensured that the UEFA official left for the club hospitality before half time and delayed him returning for the second half, meaning that he missed some of the worse incidents of trouble. However, such was the scale of the disturbances action was going to have to be taken.

The Minister for Justice, Gerry Collins TD had demanded an inquiry into the game. The findings were heavily critical of Bohemian Football Club, saying the club hadn’t employed “sufficient Gardaí” while An Garda Síochána stated that Dalymount was no longer suitable for matches of this type, that the “roof of the St. Peter’s Road stand is in danger of collapse” and that “wire around the pitch is cut in several places, and missiles are easily available on waste ground within the stadium”. UEFA were not much kinder in their appraisal; they criticised the supporters “dangerous and violent behaviour” making specific reference to the injury to Mahoney, the Newcastle goalkeeper.

It is worth contextualising the violence at the match, this was not an issue unique to Bohemians, or indeed to Ireland, at the same disciplinary meeting where Bohemians were sanctioned, fines and suspensions were also issued to Manchester City over issues arising from the behaviour of their fans and players. Hooliganism was an issue across European football, and tensions between teams from the League of Ireland and those from Britain and indeed the Irish League also took place amid the backdrop of horrific violence in the North, this was perhaps most famously encapsulated during the 1979-80 European Cup tie between Dundalk and Linfield and indeed by the return to Dalymount of Glasgow Rangers in 1984.

The punishment handed down by UEFA was that the ties for the forthcoming European Cup campaign would have to be played away from Dalymount. The club’s “home” matches would have to take place at a minimum distance of 150 kilometres from Dublin.

Despite this ban the “home” legs for the 1978-79 European Cup would bring a qualified level of success for Bohemians, as we’ll see from part two…

With special thanks to Billy Young, Tommy Kelly and Fran O’Brien for sharing their memories of the era.