A legal alien? – “Foreign” Footballers in early 20th Century Britain

“The Ministry of Labour states that professional foreign footballers are not to be allowed to play for English teams. This ruling has been promulgated in the view of the unemployment throughout the country.” – these were the words of a 1930 English newspaper report. A modern reader might be surprised to learn that not only did the Football Association not have a problem with this ruling by Labour Minister, Margaret Bondfield (Britain’s first ever female cabinet minister); they positively endorsed it. The Council of the F.A. stated they were “not in favour of granting permission to alien players to be brought into this country” and a year later in 1931, the International Football Association Board (IFAB), the effective rule-makers of the game, went even further and wrote this point into law.

This august body made up of representatives of the four “Home Nation” associations as well as FIFA stated that “a professional player who is not a British born subject is not eligible to take part in any competition under the jurisdiction of the Association unless he possesses two years residential qualification within the jurisdiction of this Association”.

This approach was not unique to football. The UK had introduced immigration legislation as early as 1905, in what was known as the ‘Aliens Act’. This act was in part a response to immigration from the Russian Empire into the UK, specifically into areas around London’s East End. Much of this immigration was from Jewish communities fleeing the upheaval in Tsarist Russian that followed the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. This political assassination triggered waves of anti-Semitic pogroms and saw a large number of Jewish people flee their homelands, escaping potential violence but also searching for new opportunities and a better standard of living. By 1901 the British census recorded 95,425 Russian and Polish Jews as being settled in Britain. Further pogroms followed in Russia in the early years of the 20th Century which in turn prompted further westward migration.

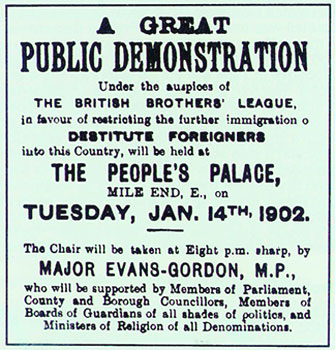

In response to this new pattern of migration, the Alien Act of 1905 was instituted after pressure from the likes of the British Brothers League (BBL), an anti-immigration group with links to some prominent Conservative MPs. They campaigned for restrictions on immigration with the slogan ‘England for the English’. The BBL had launched itself with a 1,000-strong rally in London’s East End in May 1901 and by 1902, even the future Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, then still a Bishop in Stepney, London, accused immigrants of “swamping whole areas once populated by English people”.

Anti-Semitism was very visible, especially in parts of the East End, as the Russian and Polish Jews became a prominent immigrant community, but there were also many Germans, Romanians, Austrians, Dutch and Chinese immigrants arriving during the latter years of the 19th Century and the early decades of the 20th Century.

Plaque at the Alexandra Palace

By 1930 when the FA and the department of Labour were effectively banning the transfer of foreign players, the Alien Act of 1905 had been superceded by the Aliens Restriction Act 1914 and the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919. The 1914 Act was brought in after the outbreak of World War I and obliged “foreign nationals to register with the police, enabled their deportation, and restricted where they could live“. This act was used to deal with those members of British Society deemed “enemy aliens” and in a somewhat grotesque twist of fate some 17,000 German, Austrian and other civilians were imprisoned during the course of the war in the grounds of the Alexandra Palace, the so-called “People’s Palace” managed under a Public Trust for the free use and recreation of the London public.

The 1919 Act extended these wartime conditions into peacetime and further restricted employment rights of foreign residents in Britain, barring them from certain jobs while targeting those viewed as criminals, the destitute and so-called ‘undesirables’. Under this legislation, British women lost their British citizenship upon marriage to a foreign citizen, even if the woman in question did not acquire her husband’s nationality. For children born outside Britain or its dominions, citizenship relied on descent through the legitimate male line only, and was limited to one generation. This provides some context to the actions of the FA and the IFAB. Rather than being seen as aberration from the norm, their position should be viewed as part of the wider establishment viewpoint.

A British Brothers’ League poster

The player who sparked these restrictive actions was Rudolf “Rudi” Hiden, the Austrian international goalkeeper. Hiden had starred for the Austrian national team in a 0-0 draw with England in May 1930, which likely piqued the interest of Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman. The reports of the game, played in front of some 55,000 spectators in Vienna, heaped praise on Hiden for his agility, reactions, his exceptional talent for long throw-outs, and even his good looks. The same papers did however, note that Hiden tended to use his feet too much and was unused to the British habit of barging the goalkeeper, which was considered a foul on the Continent, but not in Britain. He was also praised for his very British style of sportsmanship; upon leaving his goal to help an injured England player to the touchline for treatment.

However, despite Chapman’s interest and a fee of £2,500 being agreed with Hiden’s club Weiner AC, the transfer never went through. On three separate occasions, Hiden was turned back by immigration officials at the port of Dover after they consulted their counterparts in the Department of Labour, who determined that Hiden had no right to work to Britain. Hiden had been a baker by trade in his native Vienna, and apparently Arsenal had gone so far as to arrange a job for him as a chef in London while also being paid on the books at Arsenal. This, however, cut no ice with the immigration officials, and his move to Arsenal never materialised.

Hiden did however get his move abroad, winning a league and cup with French side Racing Club de Paris in the 30’s. He was also part of the Austrian side that trounced Scotland 5-0 in Vienna less than a year after the Arsenal debacle.

The goalkeeping options available to Arsenal in 1930 present an instructive window into the views towards “foreign players” at the time. The 1930-31 season saw Arsenal frustrated in their attempts to sign Hiden, but they were successful in signing Dutchman Gerrit Keizer from Margate. Keizer had kept goal as an amateur with Ajax before moving to London where he worked as a greengrocer while playing on the weekends for Margate, where he was spotted by Arsenal’s scouts. Keizer was initially signed as a professional but after the issues with Hiden, the Ministry of Labour forced Keizer to continue as an amateur, first at Arsenal and later at Charlton Athletic and Queens Park Rangers.

Gerrit Keizer in 1946 (source Nationaal Archief Fotocollectie Anefo )

Arsenal featured two other keepers around this time, one being Charlie Preedy, born in Neemuch, India in 1900 as the son of a British Army Artillery officer. Preedy spent the first seven years of his life in India before his family returned to England. Their final keeper was Bill Harper, a Scottish international who re-joined Arsenal in 1930, having spent the previous three years playing professionally in the United States.

The double standards were clear, Hiden was not allowed into the country and the fear was expressed that this would set a precedent for foreign players coming to Britain to take the jobs of British workers in the direct aftermath of the Wall Street crash and the Great Depression. Keizer was forced to play as an amateur and earn his living as a greengrocer. However those British players who chose to play abroad professionally as other professional leagues began to emerge (in the USA, in France and elsewhere) were free to travel and return home when it suited them.

The same went for coaches. Hiden’s international coach with Austria was Jimmy Hogan. During a hugely influential and peripatetic career, Hogan had coached club and national sides throughout Europe, from the Netherlands and Germany to Hungary and France. This Lancashire-born son of Irish immigrants perhaps did more to spread the gospel of football around the continent of Europe than any other Englishman.

Hogan was not alone in this work as a footballing missionary, other English coaches were hugely influential in developing organised football throughout Europe and beyond, bringing through new generations of local coaches and players. Men like Fred Pentland in Spain, Ted Duckworth in Switzerland, Vic Buckingham in Spain, Greece and the Netherlands or William Garbutt in Italy. Britain helped give football to the world but some didn’t want the footballers of the world to come to the home of the game. The place that they had heard so much about from their illustrious teachers and viewed with such reverence.

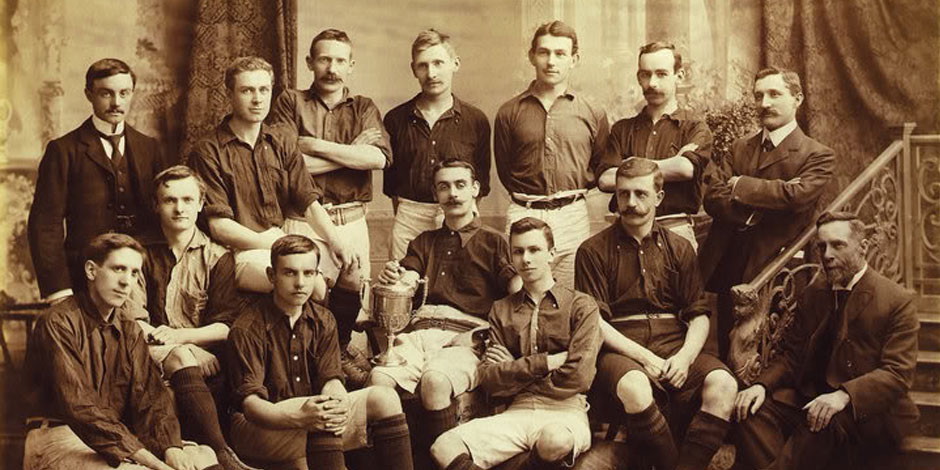

Rudi Hiden of course was not the first foreign born footballer to try to play in Britain. There were a number of players born outside Britain who had managed to make appearances in League football. In the 1890’s there was Walter Bowman from Waterloo, Canada, who twice toured Britain as part of a North American selection and was signed by Accrington (then of the first division) in 1892 before later signing for Ardwick F.C., subsequently renamed Manchester City, where he played alongside the likes of Billy Meredith.

As an infant Max Seeburg was one of those thousands who made that journey west across Europe to London in the 1880’s. Born in Leipzig, Germany he made a solitary appearance for Tottenham Hotspur in 1908 before enjoying short spells with Burnley and Grimsby Town.

The early recruitment of foreign players was haphazard, and one couldn’t identify anything approaching modern scouting or indeed any sort of systematic approach to recruitment. A player like Bowman was selected because he’d impressed on a tour to Britain. It was a similar story that led to Liverpool signing three players from a touring South African side in 1924. One of those players, Gordon Hodgson, would score 233 league goals for Liverpool (including a still-standing club record 17 hat-tricks) during his 11 years at Anfield, before being signed by Aston Villa at the age of 32 for £3,000. Hodgson was a boiler-maker from the Transvaal who was the son of English immigrants and, despite arriving in the UK as a player for a South African national team, he would end up lining-out three times for his new homeland.

As with Rudi Hiden, players were also recruited after performing well in international matches or tournaments. Nils Middleboe impressed for Denmark against England in both the 1908 and 1912 Olympics, and became the first foreign international to ever play for Chelsea. He worked in a London bank for the entireity of his career at Chelsea.

By the time of the 1930 ruling, there had even been a couple of Egyptian players appearing in the Football League. Hassan Hegazi had played against British soldiers as a teenager in Egypt, and moved to London in 1911 to study engineering. He joined non-league Dulwich Hamlet where he starred as a stylish and gifted forward, he made a single appearance for Fulham (when he scored) but decided his loyalties lay with the Hamlet in non-league football. Tewfik Abdullah had a longer league career in both England and Scotland after appearing for Egypt in the 1920 Olympics. He signed for Derby County and was referred to by one publication on it’s cover as “Derby’s Dusky Dribbler” before spending time north of the border at Cowdenbeath in the Scottish Second Division.

Either because of their status as amateurs, their parentage, or perhaps because their careers were not very high profile the players mentioned above managed to operate in British football prior to the Hiden ban. The fact that Hiden was a high-profile international, and as an Austrian a wartime enemy just over ten years before, may have impacted on his application. However, his proposed transfer spurred the Home Office into action. Among their other targets were Aberdeen, Rangers and Hearts who were all contacted by the Home Office in 1930 about the presence in their ranks of a number of Canadians and Americans, the clubs were however able to point out in each case, that although the men involved had lived in North America they were born in Scotland and had at no point taken on any other citizenship.

A player who succeeded where Rudi Hiden had failed was Bert Trautmann. Like Hiden he was a goalkeeper and like Hiden he was a former wartime enemy of Britain. In Trautmann’s case literally so. Raised in Bremen, Germany, Trautmann was an exceptional athlete from his earliest days as well as being a fervently devoted member of the Hitler Youth from the age of 10. He was a paratrooper during the Second World War and served on the Eastern Front where he witnessed the mass murder of civilians by one of the infamous Einsatzgruppen death squads. After later being transferred to the Western Front he was captured shortly after the Normandy invasions.

Trautmann eventually ended up in a prison of war camp in Cheshire and was rated as a category “C” prisoner which identified him as an ideologically committed Nazi rather than simply a soldier drafted into the German war machine against their will or despite their ideological beliefs. Trautmann gradually began a new life in England, slowly rejecting his earlier beliefs and surprisingly befriending an Jewish Army Sergeant, Hermann Bloch for who he acted as a driver, and eventually marrying an English woman named Margaret Friar. During this time he was also keeping goal as an amateur for St. Helen’s F.C., where he was spotted by a Manchester City scout and was signed by the club in 1949. As he’d been resident in Britain for more than two years and had been playing as an amateur this Iron Cross winning, Nazi paratrooper had managed to circumvent the restrictions on foreign players.

Bert Trautmann at Manchester City

Despite a protest from over 20,000 Manchester City supporters, Trautmann quickly won them, and the wider footballing public, over with a string of impressive displays. In 1956 he was named Footballer of the Year, the same year he played a famous role in City’s cup final victory when he continued playing for the final 15 minutes of the game with a broken neck after making a save from Birmingham’s Peter Murphy. In the space of a little over six years Trautmann had gone from a prisoner of war pariah into a hero and icon of the English game.

Despite occasional cases like that of Bert Trautmann, the effective ban on foreign players in England would remain in place until 1978, though Scotland took a more relaxed attitude in the 1960s, which saw a small influx of Scandanavian players immediately thereafter. The English football authorities were found to be in breach of the rule on free movement required by the European Community (EC), which Britain had joined in 1973. This EC ruling came only seven years after the UK had further amended it’s laws with the 1971 Immigration Act which meant that British Commonwealth citizens lost their automatic right to remain in the UK, and they now faced the same restrictions as those from other nations. Commonwealth citizens would in future only be allowed to remain in UK after they had lived and worked there for five years.

1978 became a watershed year for football transfers: Tottenham Hotspur signed Ossie Ardiles and Ricardo Villa, though the recently appointed PFA Chairman Gordon Taylor noted that this meant there “could already be two players out of a job at Tottenham.” Sheffield United brought in their own Argentinian in Alex Sabella, while Manchester City brought in Polish World Cup star Kazimierz Deyna.

This late 70s trickle of foreign players, however, did not turn into a flood. The rhetoric used by the likes of Gordon Taylor and PFA Secretary Cliff Lloyd was still very much language evocative of the 1930s and the Depression, and that every foreign player meant the loss of work for a British player. Lloyd warned that what started as a “trickle could finish in a deluge”, and that every “foreign player of standing in our league represents a denial to a UK player of a place in the first team”.

The FA, while complying with the European Community requirements, put in a number of qualifications: work permits would only be issued to “overseas players of established international reputation who have a distinctive contribution to make to the nation’s game”. It was, however, well into the Premier League era and the concurrent removal of player nationality restrictions in European competition before that large scale movement of international players to Britain would begin.

As Brexit approaches and certain ‘hard Brexiteers’ insist on a revocation of free movement that forms a core tenet of the European Union, there could be an opportunity to return to a type of footballing ‘Alien Act’. However, unlike the situation in the 1930s, it is unlikely that the FA, the leagues, or the clubs would welcome this. They could not so harmoniously support such regulations being imposed by government departments in the way their predecessors had. Despite almost 50 years of forced insularity, the English top-flight is now global in not only its players, but its fanbase, coaches, ownership and sources of revenue, probably more so than any other professional sporting league in the world.

It strikes me that some highly vocal advocates for a hard Brexit and the removal of free movement would feel more at home in 1930, sending a Austrian baker away at the port of Dover or insisting that a Dutch greengrocer living in London couldn’t earn money playing football. But Football has moved on from those times even if others haven’t. Britain helped bring football to the world, and looking at English football today you could say that football, in all its multifarious forms and wonderfully unusual manifestations has finally been allowed to come home.

This article first appeared in the Football Pink. The headline photo is from the mural that commemorates the Battle of Cable Street in London’s East End.

The one shown below was minted in Dublin by John C. Parkes of The Coombe and he was responsible for striking most of the pub gambling tokens.

The one shown below was minted in Dublin by John C. Parkes of The Coombe and he was responsible for striking most of the pub gambling tokens. While Grafton Street isn’t too well known for pubs today the Duke Pub, back on Duke Street is named after the 2nd Duke of Grafton Charles Fitzroy. Originally opened in 1822 the Duke Pub was run by a James Holland when they first started issuing their own tokens in the 1860’s. Since that time the pub has expanded and has taken over premises that once housed the famous Dive Oyster Bar and part of the hotel building that was operated by Kitty Kiernan and her family. It was for a time known as Tobin’s pub but has since reverted back to the original name of the Duke Bar. After a chat and a drink with David, the bar manager we were due to head onto our final watering-hole, north of the river this time to Brannigan’s of Cathedral Street.

While Grafton Street isn’t too well known for pubs today the Duke Pub, back on Duke Street is named after the 2nd Duke of Grafton Charles Fitzroy. Originally opened in 1822 the Duke Pub was run by a James Holland when they first started issuing their own tokens in the 1860’s. Since that time the pub has expanded and has taken over premises that once housed the famous Dive Oyster Bar and part of the hotel building that was operated by Kitty Kiernan and her family. It was for a time known as Tobin’s pub but has since reverted back to the original name of the Duke Bar. After a chat and a drink with David, the bar manager we were due to head onto our final watering-hole, north of the river this time to Brannigan’s of Cathedral Street.