From Jarrow to Carter and McGrory – In a Time of Hunger

By Fergus Dowd

As the dark clouds hovered above, they carried the coffin passed the shrubbery towards the church door as inside the old mixed with the young. It was Friday September 20th, 2003, and the town of Jarrow was saying a ‘farewell’ to Cornelius Whalen the last of the Jarrow Marchers, aged 93.

Whalen was one of two hundred men to walk from the town’s cobbled streets to London in October 1936 to lobby those in Westminster for work – at the time of industrial decline and poverty there was eighty percent unemployment in the town. Palmer’s shipyard was established in 1851 and was the biggest employer in the area, it built its first carrier within one year of opening and within five years it had turned its attentions to the lucrative market of warships. The founder of the shipyard Sir Charles Palmer, a Liberal Democrat MP from 1874 to 1885, had little interest in the conditions which his workers’ lived in.

Local MP Ellen Wilkinson who marched with Whalen and his comrades quotes a local scribe from the time: “There is a prevailing blackness about the neighbourhood. The houses are black, the ships are black, the sky is black, and if you go there for an hour or two, reader, you will be black”. Following the Great Depression, the National Unemployed Workers Movement began organising what the British Press coined ‘Hunger Marches’ across Britain, the 25-day Jarrow Crusade would arrive in London a week before the Sixth Hunger March. On the 4th of November 1936 Ellen Wilkinson presented the Jarrow petition to the House of Commons, it had been carried in an oak box with gold lettering, signed by 11,000 locals.

As a brief discussion followed in parliament about the Crusade, the marchers returned by train to a hero’s welcome in the Northeast; sadly, it would take the savagery of war to refuel employment in the town.

That September 1936 as Con Whalen was practicing walking along the hills of Northumberland the locals were bemoaning admission prices for a Sunderland v Celtic match at Roker Park; dubbed ‘The Unofficial Championship of Britain’. ‘Supporters from both districts will find it an expensive afternoon’s entertainment, with nothing being at stake.’ A fan wrote in his letter to the local press editor.

Horatio ‘Raich’ Stratton Carter at the tender age of twenty-three had led his hometown club Sunderland to the Championship title that April of 1936, midlanders Derby County finished runners up eight points in arrears.

A confident inside forward is how his fellow English teammate Stanley Matthews saw him: “Bewilderingly clever, constructive, lethal in front of goal, yet unselfish.” Like many from Jarrow, Carter would also join the war effort in 1939 becoming a pilot in the RAF stationed in Loughborough. Carter was considered a terrific competitor in school and presented with a gold watch, on leaving, for outstanding performances in football and cricket. George Medley a local scout had promised Carter a trial with Leicester City on reaching age seventeen, following a game with Sunderland a trial was arranged.

On a heavy pitch a couple of days after Christmas Day 1931, Carter was deemed too small for professional football by then Leicester manager Willie Orr; Orr had led Celtic to a league and cup double in 1906/07.

Carter was offered amateur terms initially by Sunderland and would become an electrician earning 45p a week; he would eventually go part time earning £3 a week training two nights a week with the Wearsiders.

Within five years the one they said was ‘too small’ would be joint top scorer for Sunderland that championship winning season and carry the trophy around Roker Park.

A few months after the Celtic match Carter would receive a benefit cheque of £650 for five years of service at Sunderland, despite a long career at the club and leading the club to the FA Cup in 1937, he would never receive another benefit.

By 1953 in the twilight of his career Carter found himself in southern Ireland lining out for Cork Athletic; it was said he was paid £50 per match plus £20 expenses, this enabled him to fly from Hull to the Emerald Isle for matches. Carter had become manager of Hull City but a rift with Chairman Harold Needler led to his departure in January of that year, he left football to run a sweet shop. However, within one month Cork Athletic Secretary Donie Forde and director Dan Fitzgibbon had performed a miracle tempting Carter to Leeside.

It proved an inspirational signing, after making his league debut versus Waterford, Carter and Cork would face Drumcondra. The Dublin club would make an objection regarding Raich’s residency in Éire, he had landed only two weeks previously, his match fee was earned as he scored the victorious goal at Tolka Park. Raich Carter would go on to win an FAI Cup winners medal with Athletic that season and play for a League of Ireland XI versus an England league select.

Glasgow Celtic arrived in Sunderland in the autumn of 1936 after winning the Scottish Championship a few months earlier, Aberdeen and Rangers finished tied for second place five points a drift.

In that winnig team was the ‘human torpedo’ Jimmy McGrory who was coming towards the end of his career, by December 1937 he would take the hot seat at Kilmarnock. McGrory was born in Garngad in North Glasgow a place commonly known as ‘Little Ireland’ given the ethnic idenities of many of the habitants. The atmosphere in the area was corroded with incessant smoke and fumes from the Tharsis Sulphur & Copper Works and the Milburn Chemical Works; in 1904 as wee Jimmy was taking his first breath on this earth the Provan Gas works was opened by Glasgow Corporation. It did nothing to improve the environment and only added to the breathing problems and illness for those in Garngad.

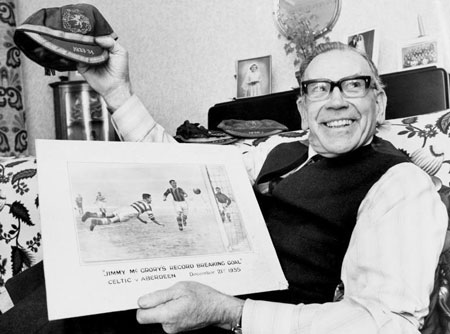

In 1921 then Celtic manager Willie Maley signed James Edward McGrory as an inside right from junior side St. Roch it would take him two years to make his debut against Third Lanark in January 1923; he had been loaned to Clydebank intially. Jimmy would be top scorer for the hoops twelve seasons in a row, and the season of 1935/36 would see him top of the European charts after netting fifty times; he was also European top scorer nearly a decade earlier scoring forty-nine times. In 1928 the Arsenal of North London offered £10,000 to make him the highest paid player in Britain. A true Celt Jimmy refused to leave Parkhead; the Celtic board hoping his departure would boost the clubs accounts were furious at his decision. So, much so they secretly paid him less wages than his fellow teammates for the rest of his career. Jimmy to the delight of the Sunderland defence was omitted from the Celtic team that Autumnal day. After notching up 472 goals in 445 league & cup appearances McGrory would retire a year after the Jarrow Crusade. Like Carter he would go on to be a manager leading to Celtic to a 7-1 victory over Rangers, a British record in a domestic cup final – ‘Hampden in the Sun’ they call it!!

On September 16th, 1936, seventeen thousand paid in at Roker Park to watch Sunderland take on Glasgow Celtic, that same day in a sign of things to come Antonio de Oliveria Salazar’s right-wing dictatorship in Portugal unveiled the Portugeuse Legion a paramiltary state organisation setup to ‘defend the spiritual heritage of Portugal”. In goal for Sunderland that day was Johnny Mapson, he replaced Jimmy Thorpe. Thorpe was netminder for Sunderland from 1930 to 1936, on his one hundred and twenty third appearance against Chelsea in February 1936 he was kicked in the head and chest but played on.

After arriving back home Thorpe collapsed and four days later in hospital, he took his last breath.

His widow was presented with his 1935/36 championship medal and the FA rules changed stopping players kicking the ball out of goalkeepers’ arms. Mapson would concede only one goal, on the hour mark to Malky MacDonald who like McGrory had started life at St. Roch’s.

Raich Carter had opened the scoring for the Black Cats on the twentieth minute and referee Harry Nattrass who had officiated the FA Cup final of 1936 drew the afternoon’s proceedings to an end.

As the Jarrow marchers arrived in the Yorkshire town of Wakefield a month later on the 14th of October, Nattrass was refereeing at Hampden Park as the Nazi emblem flew alongside the St. Andrew’s Cross.

The teams would meet again a fortnight later at Parkhead, the green and white would win out three to two this time, thirteen thousand would witness McGrory netting twice.

Today in England there are no hunger marches, although you will find foodbanks at most league grounds on a Saturday; In Sunderland Raich Carter is eulogised in written word and art, while the name McGrory rolls off the tongue easily around Parkhead.

In Jarrow there is a statue dedicated to those who walked to London and if you care to have a pint in one of the locals, an Old Cornelius should be ordered in honour of a great man.