In the ring at Dalymount

Boxing is Ireland’s most successful Olympic Sport and Dublin has produced fighters of international renown and witnessed world title fights but the city has also had a somewhat ambivalent relationship with the sport, happy to cheer on successes but often young fighters had to venture beyond our city for recognition. For more than sixty years Dalymount Park was an important venue for both amateur and professional bouts attracting big name fighters while also giving a platform for up-and-coming Irish boxers.

Dalymount Park was staging boxing matches since at least 1920 when the Irish Amateur Boxing Association (IABA) hosted an All-Ireland boxing competition there. Tickets ranged in cost from 2 shillings up to 5 shillings for ringside seats. The tournament was a great success though the closing bouts were hampered somewhat by an unseasonal July downpour which made it difficult for fighters to keep their balance on the slippery canvas.

Contests continued to be held in Dalymount through the 1920s as Bohemian Football Club made gradual improvements to the stadium. In 1928 an Irish Amateur boxing team faced off against their Danish counterparts in an international exhibition tournament ahead of the Olympics. By 1932 after some further improvements to Dalymount by renowned architect Archibald Leitch, the stadium was to hold one of its biggest ever fights, an exhibition match by the “Ambling Alp”, Primo Carnera. The giant Italian was one of the biggest names in Boxing and was just a year away from becoming heavyweight champion of the world when he defeated Jack Sharkey in Madison Square Garden in 1933.

Carnera was the headline name on a bill that included various weight divisions and fighters from all over Britain and Ireland. The 6’6”, 20 stone Carnera fought exhibition bouts against English heavyweights Bert Ikin and Cyril Woods and entertained a crowd reported to be almost 20,000. The Irish Independent called him as “light as a bantam” on his feet, and the rest of the Irish media were similarly impressed with Carnera’s boxing skills and amiable personality. Carnera, it was explained was learning his English from “the talkies” and had enjoyed the trip to Ireland apart from the crossing of the Irish Sea, berths aboard ship were not suited to a man of his size and he had found it very difficult to get to sleep. Carnera would ultimately lose his title to Max Baer in 1934, this fight features prominently in the Jim Braddock biopic The Cinderella Man which starred Russell Crowe.

The 1930s was a busy decade for boxing in Dalymount, there were more of the amateur international contests against the likes of England and Italy’s finest fighters, while more big-name professionals were brought there to fight after the success of Carnera’s visit. Boxing Hall-of-famer Freddie Miller fought the Welsh Champion Stan Jehu in Dalymount in 1935. Miller was the National Boxing Association (NBA) World featherweight titleholder at the time and had embarked on an extensive tour of Europe defending his title against all-comers. Three thousand spectators, including Government minister Frank Aiken and American Ambassador Alvin Owsley, watched Miller stop Jehu after four rounds. The same year Dalymount hosted Irish professional title fights which saw George Kelly become Irish lightweight title holder and Mossy Condon win the welterweight title.

The Irish Press writing about the bouts in Dalymount praised promoter Gerald Egan for his excellent promotional work and for arranging attractive bouts and headliners, declaring that “Professional boxing, dead as the proverbial doornail for so many years in Dublin, is sitting up and taking nourishment again – and this time it’s the right kind of nourishment”.

George Kelly, a Dubliner who had competed in the 1928 Olympics as an amateur, became a star attraction for the Dublin boxing public. Seven thousand people paid to see his title defence against Eddie Dunne in Dalymount, and there were scenes approaching pandemonium as Dunne, born in Skerries but raised in New York and fighting only his second fight outside of the United States, floored Kelly in the sixth round. The crowd yelled that Dunne had felled Kelly with a low blow as the defending champion squirmed in agony on the canvas. The crowd then stormed the ring and it took the intervention of An Garda Siochána before the final fight of the bill could proceed.

The outbreak of the Second World War created obvious difficulties in arranging international fights and bringing over top class professional boxers to Dublin. It also meant that it was more difficult for an impressive generation of young Irish fighters to hone their skills against elite level opponents. Despite this there were a number of high-profile matches. Chris “Con” Cole became the Irish heavyweight champion in Dalymount Park in 1942 when he defeated Jim Cully, flooring him seven times during the course of the fight. “Tiny” Cully was one of the tallest fighters in boxing history, conservatively measured at 7’2” he would enjoy a short, and ultimately unsuccessful boxing career, he found his greatest popularity during his couple of fights in the United States after appearing three times in Dalymount. Cully also seems to have enjoyed some popularity as a wrestler after he hung up his gloves. There is some great footage of the Dalymount fight here.

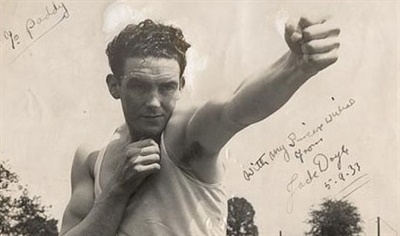

The following year would see one of the biggest fights in Dalymount history, but also one of its most disappointing. Cole was the opponent for the return of the “Gorgeous Gael” – Jack Doyle, almost four years after his last fight in London against Eddie Phillips. Doyle was a larger-than-life character, standing 6’5” he was a boxer, singer, actor, racehorse owner (he had a disagreement with former Bohs captain, and bloodstock agent Bert Kerr over a horse which ended up in a court case) and socialite. Doyle claimed that in terms of boxing he was the next Jack Dempsey and in singing he was the next John McCormack, he married the movie star Movita Casteneda in Westland Row church in Dublin in 1939 and stopped traffic in the city as the locals craned their necks to see a man who had packed out theatres with his singing and brought 90,000 to White City for his fight with Jack Petersen.

Sadly, by the time his fight in Dalymount rolled around Doyle was a shadow of himself. He was descending into alcoholism and had become a caricature of himself, reportedly heavily indulging in liberal amounts of brandy before previous bouts. For his fight with Cole he had “Cyclone” Billy Warren as his cornerman, a veteran black, American (or possible Australian) boxer, Warren had claimed to have fought Jack Johnson in his prime. Whatever the truth of this Warren had ended up in Dublin in 1909 and had later become Irish heavyweight champion. But all of his experience couldn’t help Jack Doyle. His fight against Cole was over within a round, Doyle managed only two and half minutes of “boxing” which he mostly spent clinging to the ropes as Cole pummelled him. The referee stepped in to stop the fight as it seemed that Doyle was unable to defend himself. What many Dubliners (and the media) had hyped up to be the “fight of the century” was finished and almost 20,000 disappointed fight fans left Dalymount in shock.

It is perhaps testament to the appeal of Doyle that even after his defeat to Cole thousands returned to Dalymount only two months later when Doyle once again topped the bill, this time they witnessed three rounds of boxing with Doyle emerging victorious over Cork heavyweight Butcher Howell. It was to be Doyle’s last professional fight, though he would later appear as a wrestler in Tolka Park. Doyle later ended up in penury, holding down work as a nightclub bouncer. His wife Movita, tired of his womanising and violent abuse, left him, she later married Marlon Brando. Jack Doyle, arguably the most famous Irishman in the world at one stage died in 1978.

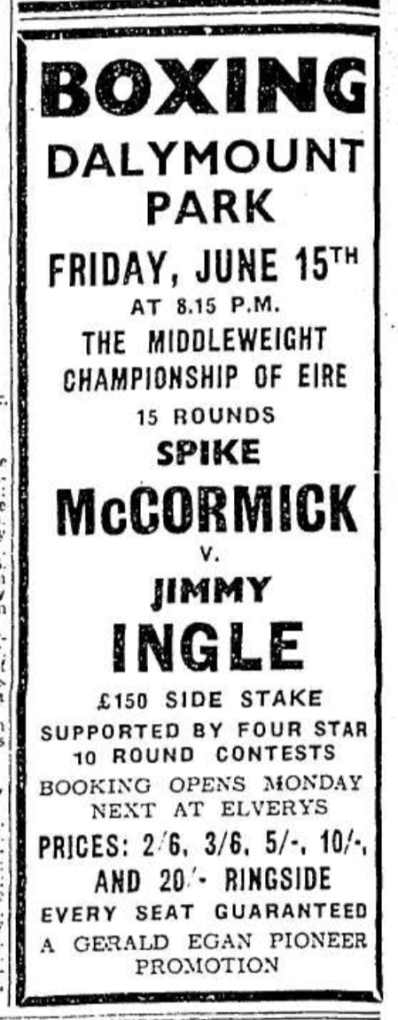

While Doyle’s career might have come to an end in Dalymount others were only approaching their zenith. The Dublin sporting public became enthralled by the developing sporting rivalry between John “Spike” McCormack and Jimmy Ingle. Both fighters were familiar to each other from the amateur ranks. Ingle had gone on to win gold at the European Amateur Championships which were held in Dublin in 1939 while Spike had enlisted in the British Army early in the War. After being invalided out Spike went pro in 1942, as did Ingle. Spike making his Dalymount debut a year later. In 1944 both fighters would face off in Dalymount Park for their first meeting as professionals and would renew a long-standing sporting rivalry from their amateur days. Spike would win that fiercely contested bout on points but the great spectacle created a demand to see the pair in action again.

As Ciarán Murray notes, the “men would fight each other a further four times in the space of three years, twice for the Irish middleweight title. Spike would win both of these fights, before fighting to a draw in a bout in Dalymount in June 1945, and Spike losing to Ingle in May 1947 in Tolka Park”. That drawn fight in June of 1945 would etch itself into the city’s sporting memory. Writing almost forty-five years later the Bohemian F.C. board member and club historian Phil Howlin would recall;

“there was a 15 round, middleweight contest between two really good fighters from Dublin, John (Spike) McCormack and Jimmy Ingle. 15 rounds of one of the fiercest fights we had ever to witness, they virtually threw everything short of the kitchen sink at each other. It ended in a draw to the rapturous applause of a big crowd. Faith had been restored in Professional Boxing in a big way.”

Spike McCormack, as well as being a boxer, British Army commando and Dock labourer also worked for Des Kelly carpets for many years. He and Ingle remained good friends outside the ring. The Ingle name would become synonymous with boxing, a younger brother, John Ingle also fought in Dalymount on the same bill as his brother in 1945. He later became Irish lightweight champion. Perhaps the most famous Ingle was Brendan, another younger brother in a family of sixteen children. While he boxed as a middleweight in the 1960s and 70s he became much better known as the man who trained four world champions including Prince Naseem Hamed.

With the end of the Second World War there was also an opportunity to bring in more fighters from outside of Ireland – in 1946 Jimmy Ingle fought French boxer Robert Charron while on the same bill the light heavyweight Pat O’Connor defeated Ben Valentine, a fighter from Fiji who would later spend time as a bodyguard for screen idol Mae West during her tour of Britain.

The biggest draw in those post war years was undoubtedly the arrival of Lee Savold – the “Battling Bartender” of St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1949. Savold was already a household name for any boxing fan, and a year later he would defeat Bruce Woodcock in White City to claim the European Boxing Union’s version of the World Heavyweight title. His final fights in 1951 and 1952 were to be less successful, losing to the great Joe Louis before bowing out against a 28 year old from Brockton, Massachusetts named Rocky Marciano.

During his exhibition fight in Dalymount, Savold took on Irish heavyweight champion Gerry McDermott for four rounds as well as two rounds with Canadian champ Don Mogard. Newspaper reports describe how Savold “toyed with them like a good-natured bear”. Though the crowds were there to see an exhibition by Savold the fight of the night was lightweight contest between Paddy Dowdall and the Canadian, Jewish fighter Solly Cantor which ended in a draw.

The days of world-famous names gracing Dalymount became less frequent in subsequent years but there were still occasional big draws for the fistic arts. Perhaps the most famous was in 1981 when Charlie Nash defended his European lightweight boxing title at the Phibsborough venue. Nash was from Derry and had represented Ireland at the 1972 Olympics but was knocked out of the competition in a quarterfinal by the eventual winner, Jan Szczpanski of Poland. That he had fought at all is testament to his character as the Games came just months after his brother Willie, was shot dead, and his father, Alex, was shot and wounded during the Bloody Sunday massacre. The horrible task of identifying his 19-year old brother’s body fell to Charlie. As he later told the Derry Journal; “Had there been no Olympic Games that year, I would’ve probably ended up in the IRA.”

Nash had hoped that the successful defence of his European title in Dalymount against Giuseppe Gibilisco might propel him to another shot at the World lightweight title, but it was not to be, Gibilisco made Nash endure six punishing rounds before the brave Derryman was knocked out. Such was the concern for Nash’s health that he recalled “I had to be rushed by ambulance to hospital. I can remember the sirens blasting as it sped through the streets of Dublin. They had to examine me and I had a concussion. I was expected to beat Gibilisco but he was a strong featherweight. It was outdoors in Dalymount Park and it was a cold, cold night for me.”

While Charlie Nash might have been coming towards the end of his career another young fighter made his professional debut on the undercard that night, 20-year-old Barry McGuigan defeated Selvin Bell by TKO in two rounds, little did we know the heights that his career would reach.

It’s important to remember that while Dalymount is synonymous with football that for many years a variety of sports were played there, everything from tennis, to croquet, Rugby league to skittle bowling, and a significant part of that history is caught up with boxing. It has been some time since a fight of note has been hosted at the ground. Roddy Collins was apparently involved in trying to secure Dalymount as a venue for a proposed fight between his brother Stephen and Roy Jones Jnr. and an honorable mention should go to Dave Scully and all who raised money back in 2013 for Bohemians during the Dalymount Fight Night. Perhaps with a redeveloped stadium Dalymount may once again witness the exponents of the sweet science do battle.