By Fergus Dowd

On the 7th of March 1986, John Ryman, MP for Blyth Valley, rose to his feet in the House of Commons ‘I wish to raise the decision of the National Coal Board to close Bates colliery in Blyth’ he stated. The 200-foot-high head gear had been part of the Northumberland landscape since 1935, employing eight hundred and ten people. By 1970 one thousand nine hundred and fifteen souls went down the pit with helmets, cap lamps, belts, and batteries to dig coal.

On that Spring day, Ryman laid out the facts to those listening ‘The colliery, in Northumberland, used to employ nearly two thousand men. That number was later reduced to one thousand seven hundred and then one thousand four hundred, and, by agreement with the NCB, it now employs eight hundred and eighty men. There are 29 million tonnes of high-quality workable reserves.’

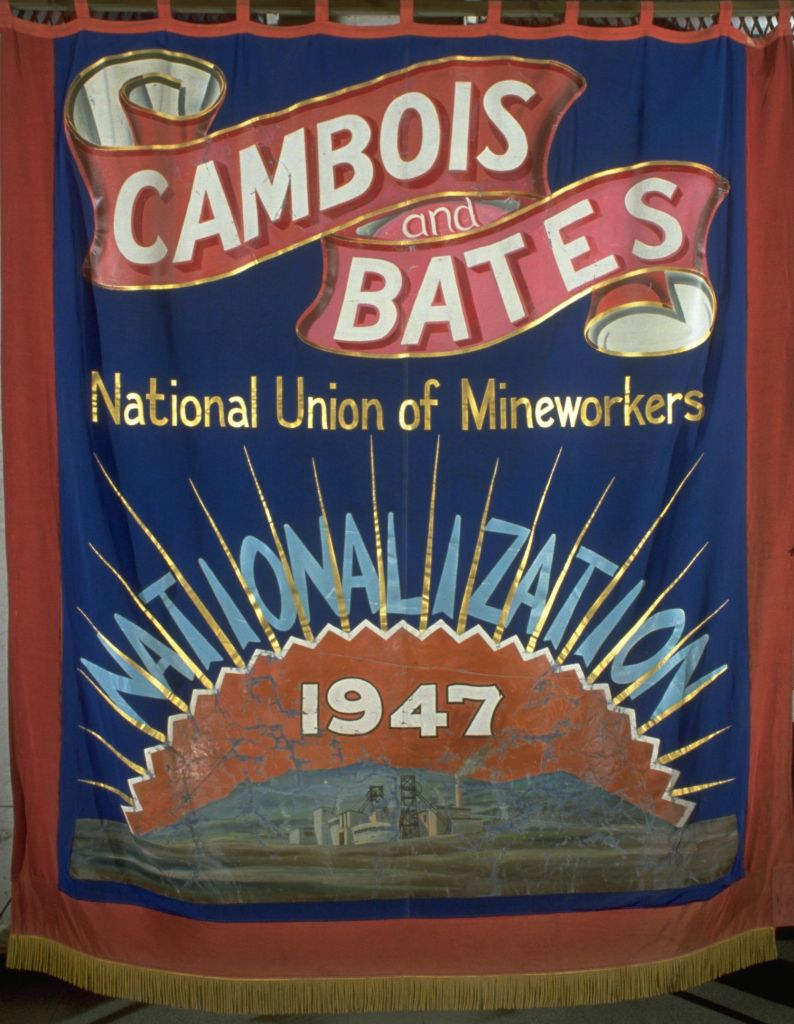

The coal industry had been nationalised in 1947 with government investment, new equipment, and mining techniques coming to the fore. However, within a decade, with competition from oil and the middle east, collieries began to close.

On the 9th of January 1972, the miners went on strike in a significant dispute overpay; it was the first time the workers from the mines had taken such official action since 1926. The miners had not got a pay increase since 1960, and workers’ wages lagged well behind other industries. Ted Heath, the Conservative leader, caved in, and the miners received a rise returning to work on the 28th of February 1972. By the 1980s, the British mining industry was one of the safest and efficient globally, although Margaret Thatcher had other ideas.

The Conservative leader and her government were all about ‘cuts’ and slimming down industries which they believed were not profitable; British Telecom became the first service provider to be de-nationalised; the mines were soon to follow, ripping apart communities in the North of England. One of those communities was Blyth, about twelve miles north of Newcastle, the coastal town that Thatcher forgot to close down.

Six minutes from Bates Coillery via Cowpen Road and behind the rows and rows of pit worker houses is Croft Park, home to Blyth Spartans. In the clubhouse of a Saturday, you will find Geordies and Mackems mixing over a pint of Double Maxim or a Brown Ale as dotted around the walls are photos of historical battles on the football pitch.

Those battles started way back in 1899 when the club was founded by 21-year-old Fred Stoker, who would end up a Harley Street Doctor with a passion for horticulture. At his home at no. 13 Blyth Terrace is where the first meeting of Blyth Spartans Athletic Club took place, the name suggesting football was not the only sport the committee had an interest in. Stoker chose the name ‘Spartans’ after the Greek army, hoping those who would wear the shirt would give their all.

Spartans started life in the East Northumberland League in 1901; the record books show an early success, the team playing its games at the Spion Kop. The ground was named in memory of those local British soldiers who perished during the Boer War in 1900 trying to relieve the besieged city of Ladysmith.

It would be four further seasons before the Spartans would win the league again, at that stage Fred Stoker would leave the North East for new pastures. One of his last duties would see him make a presentation to captain George C. Robertson, who took up a position with the bank. After further league success in 1906-07, the club joined the Northern Alliance championships winning titles in 1908-09 and 1912/13, before they joined the semi-professional North Eastern League. The club had moved to Croft Park in 1909, playing Newcastle United Reserves on the 1st of September with 2nd Viscount Ridley starting the game punting the ball goalwards.

As the Great War began, football was suspended in England. On the evening of the 14th of April 1915 the town of Blyth was visited by the Zeppelin L-9, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Mathy. Mathy had received permission to launch a raid over the North East; at 7:45 pm, the L-9 made landfall at Blyth.

For only the second time in its history, bombs were dropped on England as Mathy unloaded some of his arsenal on the habitants of West Sleekburn, five miles from Blyth. As thousands of locals joined the war effort, most signing up to the Northumberland Fusiliers consisting of seven battalions, the voices of lady footballers could be heard around Croft Park. The team was the ‘Blyth Spartans Munitionettes’, who would lift the Alfred Wood Munition Girls Cup before women playing football was banned by the F.A. in 1921. Fearing that the women’s game would affect football league attendances after the Great War, the authorities felt compelled to act.

On the 9th of March 1918, as the 158th Infantry Brigade captured Tell ‘Asur in the Jordan Valley at St. James Park, the Spartans ladies took on Armstrong-Whitworth’s 57 Shell Shop. Annie Allen opened the scoring in front of 10,000 spectators; however, Ethel Wallace equalised for ’57 before the break. With five minutes remaining and a draw looking inevitable, the great Bella Reay struck with a solo goal for the Spartans, putting the team into the final. Reay, the daughter of a coal miner from Cowpen, would notch up one hundred and thirty-three goals in one season with Blyth.

Bolckow, Vaughan & Co. of South Bank were the Spartans opponents; the game would go to a replay after an initial nil-nil draw at St. James Park, viewed by 15,000 spectators with the 3rd Battalion Northumberland Volunteers band travelling down on the train with the team. The replay was eventually played on the 14th of May at Ayresome Park, Middlesboro, in front of 22,000 spectators; Blyth would run riot, winning 5-0 with Reay and Mary Lyons starring.

It would take the men of Blyth seventeen years after the end of the Great War to win the North Eastern League in 1936/37; by 1958, the league had folded. After trying their luck in the Midland and Northern Counties Leagues, Blyth Spartans turned amateur joining the ranks of the Northern League in 1964.

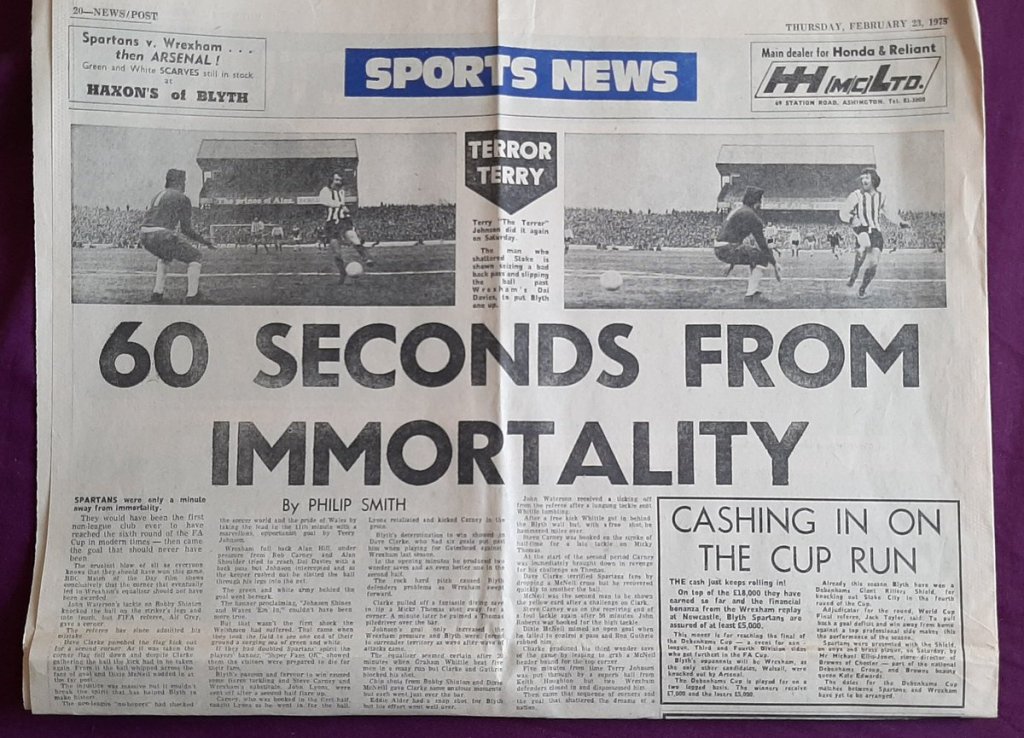

In 1977/78, as the Sex Pistols burst upon an astonished British public, Blyth Spartans would become the most famous non-league club in English football history through their displays in the oldest cup competition. It all started on the 7th of January; the same week, Johnny Rotten asked an American audience, ‘Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?’ Alan Shoulder, a miner, netted to eliminate Enfield and bring their 32-game unbeaten run to a thundering end in the F.A. Cup third round. The green and white hordes headed for the Potteries on the 6th of February in round four to face second division Stoke City; it was the third attempt to try and fulfill the fixture.

Fifty-two official coaches from the North East arrived at the Victoria Ground on January 28th with an hour to kick off the game was called off due to flooding; the elements continued to play havoc with a further cancellation on the 1st of February. However, on a damp Monday night, the Spartans ran out 3-2 winners with Shoulder’s partner Terry Johnson sending the Northumberland travelling army into raptures after twelve minutes with his fourteenth goal of the season stabbing the ball home after a calamatious error by Jones in the Stoke goal. Spartans incredibly led as the players went for their teatime break, a rejuvenated Stoke looked like they would spoil the party as Viv Busby equalised, and then future BBC analyst Garth Crooks gave Stoke a 2-1 lead. Sensationally Steve Carney, who would sign professionally for Newcastle United in 1979, reacted quickest to an Alan Shoulder header which had hit the post; incredibly, the tiring part-timers had found an equaliser.

As a replay at Croft Park loomed, Terry Johnson popped up to score, rifling a right-footed shot past the hapless Jones in front of a disbelieving Spartans faithful. In the fifth-round draw, Blyth Spartans would face local rivals Newcastle United or Wrexham. A dream tie at St. James Park was ruined when the Welshmen won a replay against the Magpies four to one; the green and white army would be heading to the valleys.

The game would be televised, and so Match of the Day viewers would witness how close the Spartans would come to immortality; coach Jackie Marks had proclaimed to the media that week the team’s secret ingredient ‘speed oil’ a pre-match drink to release matchday tension. Infatuated with manager Slane the teacher, Carney, an electrician, and Shoulder, the coal miner, the Spartans became both local and national heroes as the sports hacks tried to find out more about the giant-killers.

As a local supermarket invited the players to do their weekly shopping for free, in the build-up, twenty-year-old Steve Carney announced how he was due to get married and might have to delay it if Spartans were to achieve the impossible. The dream looked on when Terry Johnson opened the scoring in the Racecourse Ground nipping in after a poor backpass by Alan Hill on a bone-hard surface, placing the ball between Dai Davies legs. Blyth’s F.A. Cup journey began in September 1977 as 2,000/1 outsiders they were now leading one-nil and dreaming of the quarterfinals.

Incredibly the Spartans held out until the final play with Dave Clarke superb in goal; there was sixty seconds on the clock when John Waterson cleverly played the ball off Wrexham’s Shinton for a goal kick. As most in the ground expected Clarke to take the goal kick, referee Alf Grey inexplicably pointed for a Wrexham corner; as the corner flag leaned over like the Tower of Pisa, the referee went over sticking it into the frozen ground, so it stood correctly upright. Cartwright then sent over a curling right-footed corner which Clarke rose to punch away for another corner as the amateur whistles sounded out around the Racecourse. Again, Cartwright took the corner this time, Clarke rose nonchalantly to collect the ball; it seemed history was to be made not since Queens Park Rangers of the Southern League in 1914 had a non-league team reached the sixth round. Alas, Grey had spotted the corner flag lying on the ground when Cartwright took the corner and instructed it to be re-taken. This time Roberts rose with Clarke, and Dixie McNeil broke every heart in the North East.

The replay would take place at St. James Park 42,000 would turn up on the night, and thousands would be locked out, Spartans would succumb to a 2-1 defeat with Johnson netting once more. It was the end of the dream.

In Blyth today, on the gable end of Gino’s Fish and Chip Shop, renowned Sunderland-based artist Frank Styles will create a mural of modern legend Robbie Dale. Dale spent fifteen years at Croft Pak wearing the green and white shirt 680 times and netting 212 goals. It is the brainchild of Simon Needham a Leeds fan who grew up in an era when the names Revie, Giles, and Bremner rolled easily off the Yorkshire tongue.

Like the Spartans founder Stoker, Needham is something of a horticulturist, a landscaper by day he cultivates gardens in Blyth and surrounding areas. He has recently gained a master’s from Sunderland University. On moving to Blyth, he became a regular at Croft Park while also travelling up the highways and byways in support of the non-league side. In an era of super leagues and billionaire foreign owners, Needham spearheaded a campaign to raise £5,000 to create the mural, amplifying the saying ‘football is nothing without fans.’

Around Blyth, the pits have been replaced by wind farms, but in the clubhouse, there is still talk of corner flags and women heroes in a place where football still has a soul.