The Story of Stan Kobierski – From Dalymount Roar to Siberian Railtracks

by Fergus Dowd

As the snow drifted up to his waist in the Siberian wilderness and the wind stung his face, the Gulag prisoner Stanislaus Kobierski dug, lay, and scraped. He would receive 200 grams of bread and a cup of water for his efforts while all around him bodies dropped dead; 300,000 would perish as temperatures plummeted to minus fifty.

The project was the Trans-Polar mainline, Joseph Stalin’s attempt to conquer the Arctic Circle.

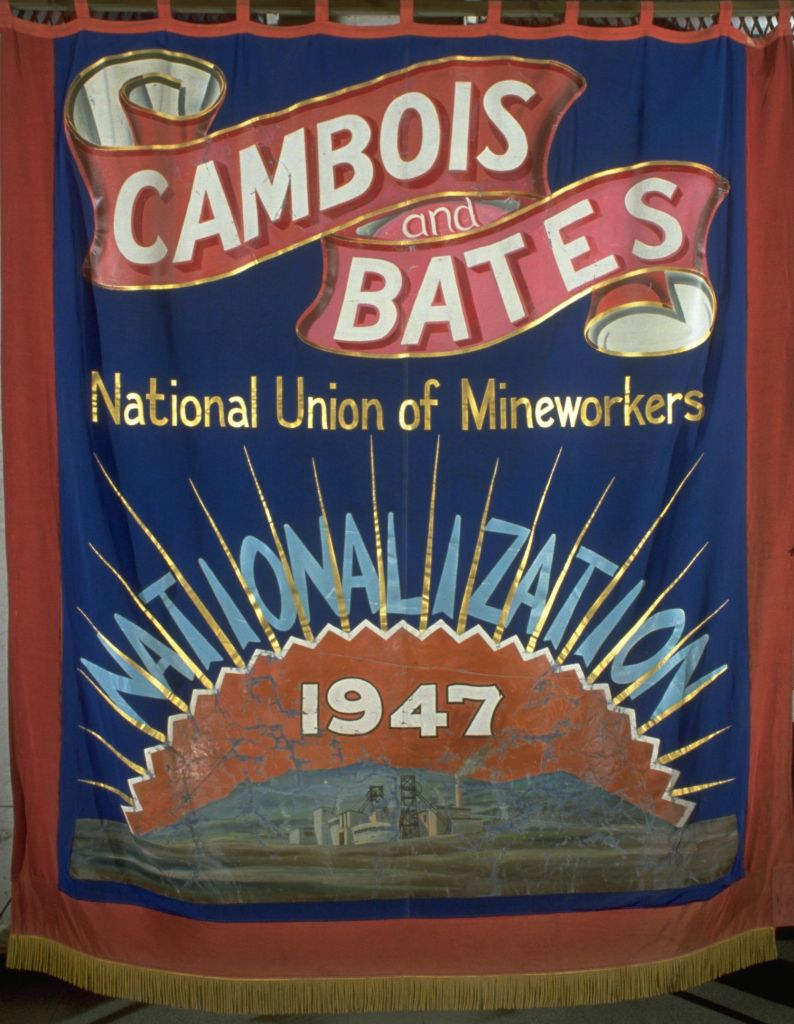

An audacious scheme to link the eastern and western parts of Siberia by one thousand miles of railway track from the city of Inta via Salekhard to Igarka lying on the Yenisei River. The track that Kobierski lay had the acronym ZIS written into it – it stood for ‘Zavod Imeni Stalina’ factory – named after the Russian leader. Kobierski was part of the 501st labour camp which began work eastward towards Salekhard in 1947 under the supervision of Col. Vasily Barabanov, who would be decorated with the order of Lenin in 1952. All around the camp were watchtowers; any thoughts of escape would be met with the firing squad.

More than a decade earlier, Stanislaus Kobierski had landed in Balmoral Aerodrome on the outskirts of Dublin from Scotland; in his bag were his football boots. It was October 16th, 1936, and two days before Kobierski and his German teammates had given the Nazi salute to sixty thousand Scots at Ibrox stadium. The crowd cheered on seeing this unusual sight as ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’ was struck up as the Swastika flag fluttered in the wind alongside the Union Jack.

At half time a protest took place against the new wave German regime, two of the instigators were arrested and removed from the ground. The Scots ran out two-nil victors with Celtic’s Jimmy Delaney netting twice; Delaney would run out for Cork Athletic in the 1956 FAI Cup Final. Then aged 41, Delaney of Irish descent, who was reared in the Lanarkshire mining village of Cleland, would be denied the opportunity to obtain a unique collection of cup winners medals across the British Isles after winning the IFA Cup with Derry City in 1954, the Scottish Cup with Celtic in 1937 and the FA Cup with Manchester United in 1948.

As Kobierski and his colleagues disembarked from the plane which carried Nazi flags on the tailfin, President Eamon DeValera and Dublin’s Lord Mayor Alfie Byrne stepped forward to welcome the travelling party. The team stayed in the Gresham Hotel on O’Connell Street and were brought into town in a bus adorned with the ancient religious icon from the cultures of Eurasia. Like Ibrox before the playing of anthems, the Germans gave their infamous salute to the main stand at Dalymount Park as locals watched on.

In the 26th minute Kobierski, at the home of Irish football, scored, equalising for the Germans after Dundalk’s Joey Donnelly had netted a minute earlier for the Irish. That same year Kobierski had won the Gauliga Niederrhein with Fortuna Dusseldorf. They would become the most successful German side, winning five championships throughout the reign of the Third Reich. The league was one of sixteen top-flight divisions introduced by the Nazi sports office in 1933, replacing the Bezirksligas and Oberligas as the highest level of play in German football competitions.

Fortuna would reach the national league finals losing out to F.C. Nurnberg two-one after extra time; Kobierski’s colleague on that day in Dalymount, Andreas Munkert would lift the title in Berlin. However, there would be no glory in Dublin for Munkert as he and his defensive partners were run ragged by Paddy Moore and Donnelly, as a marauding Irish team ran out 5-2 winners. One of Schalke’s greatest ever players, Fritz Szepan, scored the German’s second goal. He won six championships and a cup final medal for Die Knappen and was voted on the greatest Schalke team of the century when the club celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2004.

Szepan played for Germany in the second World Cup in 1934, hosted in Italy; Kobierski would score Germany’s first-ever championship goal against Belgium as the Germans would finish a respectable third in the competition.

Both would feature in the ‘Unified German’ side, which would also include some of the great Austrian players from the iconic Wunderteam after the Anschluss.

The Austrians played their last match as an independent nation on the 3rd of April 1938 at the Prater Stadium in Vienna against Germany; dubbed ‘the homecoming match’, the Austrian side ran out two-nil winners.

Their star forward, Matthias Sindelar, known as ‘The Mozart of Football’, scored one of the goals that day. Karl Sesta got the second an audacious lob, which led to Sindelar dancing in front of the VIP box in celebration, which housed Nazi leaders and their Austrian satraps.

Sindelar was found dead in his flat within a year, alongside his girlfriend Camilla Castagnola, both asphyxiated by a gas leak. In Austria, they still wonder about the mysterious circumstances of the deaths – suicide, an accident, or murder? On that autumnal day at Dalymount, the joyous Irish public invaded the pitch at the end, even cheering the Germans off the pitch, some raising their arms in the salute they had witnessed earlier.

In 1941 after over a decade with his hometown club, Kobierski, whose parents hailed from Poznan, was ordered to line out for the SS & German police club in Warsaw for exhibition games. On the 1st of September 1939, Germany had invaded Poland from the West, while seventeen days later, the Soviets invaded from the East; by October, Poland was defeated. Unlike their German counterparts, the Soviets allowed league football to be played primarily in the city of Lwow, the birthplace of football in Poland.

One of the teams in East Poland was Junak Drohobycz, a side who were actively involved in the Polish resistance movement; the players all in their twenties were also soldiers helping people escape to Hungary across the Carpathians. The team were known as ‘The White Couriers’ and ended up playing matches in Hungary and Yugoslavia during the war. One of the ‘Couriers’ was goalkeeper Stanislaw Gerula, who played for Leyton Orient of London in 1948. Gerula would spend two years at Brisbane Road before turning out for non-league Walthamstow Avenue playing in nets against Arsenal at Highbury in the London FA Challenge in 1952. That same year, Gerula helped Walthamstow win the FA Amateur Cup at Wembley; he was 38 years young. Twelve months later, Gerula rolled back the years against a Manchester United team who had won the championship in 1952 captained by Jackie Carey; in the fourth round of the FA Cup, the amateur side would draw 1-1 at Old Trafford as the ‘Courier’ performed heroics in goals.

In mid-1942, Kobierski and his team faced Huragan Wolomin in Legionowo; the Christmas of 1941 had seen the start of the underground Warsaw District of Association Football league. The Germans banned the league, and most games were played in the suburbs, such as Wolomin, Góra Kalwaria, Brwinow, and Piaseczno, as it was too dangerous to play games in the city. Alfred Nowakowski founded the league an ex-Legia Warsaw player; he would be awarded the Golden Cross of Merit in 1946, a Polish civil state decoration.

On the 1st of August 1944, the Polish Home Army initiated the Warsaw uprising, a non-Communist underground resistance movement to liberate the city from Germany. Forty-five thousand members fought alongside another 2,500 soldiers from the National Armed Forces and the Communist People’s Army against the military might of the Germans. Only a quarter of the partizans had access to weapons. Alongside this came the ‘Red Army’ appearing along the east bank of the Vistula River, Kobierski would eventually be captured and sent to Siberia.

The uprising would last for sixty-three days and be suppressed by the Germans in Oct 1944; with civilians deported to concentration and labour camps, the intensive fighting would reduce Warsaw to ruins. Stanislaus Kobierski would remain in Siberia until 1949 and, on his release, return to live out his days in West Germany, passing away in 1972.

Before he took his final breath, Kobierski witnessed his beloved Fortuna finishing third in the Bundesliga and qualifying for European competition for the first time in the club’s history. Football was all he knew, but it took him from hell and back.