Death in the Fifteen Acres

A hard tackle on a bare, wintry, public pitch and two players go down in a tangle of limbs. Both rising, angry words, then fists, are thrown – the referee intervenes and both players, one aged 17, the other 23, are sent from the pitch. Not the finest example of the beautiful game, but not exactly an uncommon occurrence across the parks and playing fields of Ireland. It is what happens afterwards, the minute or two of frenzied violence that is unusual and shocking, moments of chaos that leave a young man dead and will see three amateur footballers stand trial in a Dublin court for murder. This is the story of the death of Samuel O’Brien.

The Fifteen Acres

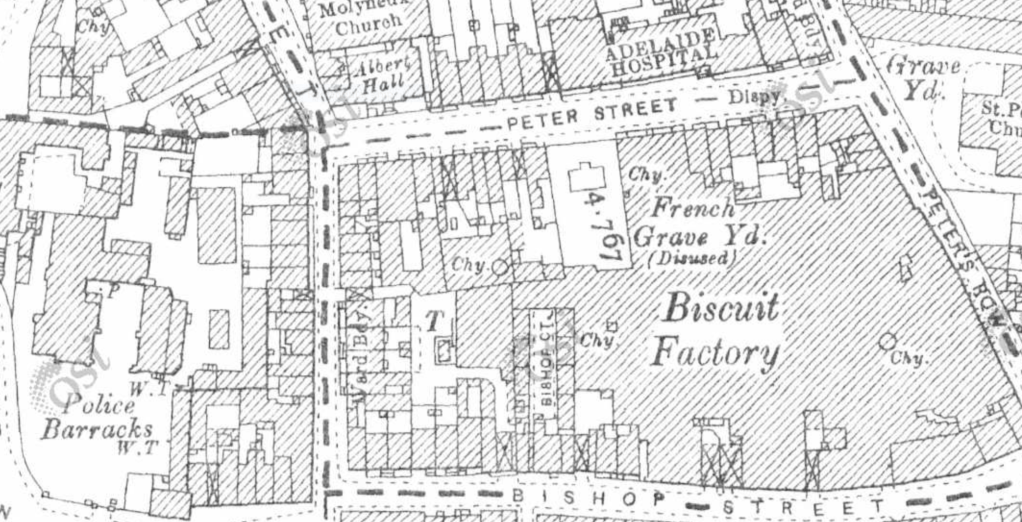

The Fifteen acres of the Phoenix Park has a legitimate claim to be the footballing heart of the city. Located in the expanse between the Magazine Fort and the Hibernian Military School (now St. Mary’s Hospital) it occupies land that were once the parade grounds and firing ranges of the British Army in Dublin. A short distance away at the North Circular Road gate-lodge the Bohemian Football club was founded in September 1890, there are reports that early members of the club included some from the Hibernian Military School among their number. Bohs first pitches were at the nearby Polo Grounds, on the other side of Chesterfield Avenue.

In 1901 the Commissioner for the Board of Public Works agreed to lay out a number of playing pitches in the area of the Fifteen Acres. Out of the thirty-one available pitches twenty-nine were used for soccer. This meant that clubs with limited means or without a pitch of their own had somewhere close to the city to play. Among those to host their early matches on the Phoenix Park pitches were St. Patrick’s Athletic from nearby Inchicore. The park pitches remain in almost constant use to this day, and their footballing significance has even made it into the public shorthand (perhaps unfairly) for poor or amateurish play, via the utterances of the likes of Eamon Dunphy declaring that “you wouldn’t see it in the Phoenix Park”.

This part of the park has also seen it’s share of violence. At the edge of the Fifteen acres close to Chesterfield Avenue and almost opposite to the Viceregal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin) on a spot of ground now marked by a discreet commemorative cross, one of the most infamous murders in Irish history took place when, in 1882 The Invincibles murdered Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke with a set of surgical knives. Cavendish was the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, having arrived in Dublin just that day, while Burke was the Permanent Undersecretary, the most senior Irish civil servant.

During the 1916 Rising the Magazine Fort was targeted by the Irish Volunteers led by Paddy Daly. Hoping to sieze weapons and destroy British stocks of ammunition and explosives, the members of the Volunteers posed as a football team, passing a ball back and forth as a diversion, until they were close enough to rush the guards and secure the fort. One of the sentries of the fort suffered a bullet in the leg, while George Playfair Jnr. – son of the Commandant of the fort was killed by bullet wounds to the abdomen when he tried to raise the alarm. In more recent times the area just east of the fifteen acres near the Wellington monument was the site of one of the notorious GUBU murders carried out by Malcolm MacAthur when he bludgeoned to death a young nurse, Bridie Gargan, while she lay sunbathing on the grass on a summer afternoon in 1982.

The scene on matchday 1924

Returning to the match in question – a Leinster Junior Alliance division four match between Glenmore and Middleton, two Dublin teams, in the Phoenix Park. Middleton held their club meetings at 35 North Great George’s Street in the north inner city but featured several players from the southside of the inner city. Glenmore (sometimes styled as Glenmore United) were from south of the Liffey and used 30 Charlemont Street as their address.

The game took place on the 7th December 1924, on pitch 28 of the Fifteen acres, an area that remains a focal point for amateur football in Dublin City. It was a fine, dry day for the time of year, though there was a strong breeze blowing in from the west.

The game itself seems to have been proceeding relatively without incident when according to referee James Rocliffe, with a quarter of an hour remaining, Samuel O’Brien of Middleton was going through with the ball when he was tripped by Patrick Lynam of Glenmore. The referee called a foul and O’Brien, obviously aggreived at the challenge got up in “a fighting attitude” and he and Lynam rushed at each other, trading blows. At this point Rocliffe separated the pair, sent off both players and prepared to restart the game.

However, his action in sending off both players hadn’t eased tensions. The pitches of the Fifteen acres not being served with individual pitch-side dressing rooms both players went behind one of the goals after being sent from the field. Here, tempers flared again with Lynam and O’Brien trading punches and other players rushing from the pitch to intervene, just as Rocliffe was trying to restart the game.

The fatal blow?

What happened next becomes a matter for debate, one which I will try to tease out and present for the reader based on the court testimonies of those present on the day. The version of the story changes with each retelling and with each narrator. What seems to be generally agreed on is that as Lynam and O’Brien set at each other again after their sending off, other players joined the fray, ultimately O’Brien was knocked to the ground and it seems it was then that he was kicked in the head, or possibly struck his head heavily off the ground as he was knocked over. This according to the medical examiner was likely the cause of his death, aged just 23.

In the aftermath the referee retreated to the relative safety of the nearby pavillion, while Thomas Ralfe, a teammate of O’Brien, seeing that his friend was badly injured rushed to the nearby Hibernian School, then in use by the National Army, and sought help. He returned with two army officers who gave O’Brien first aid as they waited for the Dublin Corporation ambulance to arrive to take the stricken footballer the short journey to Dr. Steeven’s hospital.

Samuel O’Brien, arriving at the hospital unconscious, was met by the house surgeon Dr. W.A. Murphy just after 3pm that day. Murphy described O’Brien as being in a state of “profound collapse” and growing steadily worse. Despite medical intervention Murphy would pronounce O’Brien dead later that day at 7:45pm. In the post-mortem report the cause of death was identified as “paralysis of the respiratory centre caused by the compression of the brain by haemorrhage”. To the untrained eye O’Brien appeared to show just minor, superficial injuries; bruising to the right eyelid and a couple of minor abrasions around the same eye. There were no other obvious injuries or bruising to suggest trauma to major organs. It was only upon the opening of his skull that the violence he had suffered was laid plain. The entire of Samuel O’Brien’s brain was covered in blood. The haemorrhage that had killed him caused by significant trauma to the head.

Inquest

The following day, Monday, December 8th 1924 – Dr. Murphy had the opportunity to present his findings to an inquest held in Dr. Steevens’ Hospital chaired by City Coroner, Dr. Louis Byrne and a jury, to decide if the death of Samuel O’Brien should proceed to trial. When describing the injuries recieved by the deceased, Murphy stated that they could be caused by “a person being struck in the face and falling to the ground”.

Present at the inquest apart from Doctors Byrne and Murphy were a Mr. Clarke, representative of the Chief State Solicitors Department, Inspector Patrick Guinan of the Bridewell, Dublin Metropolitan Police and the three young men suspected of causing injury to Samuel O’Brien – they were Patrick Lynam, aged 17, a bookmakers clerk from St. Patrick’s Terrace off the North Strand, Michael Doyle, aged 18, at the time unemployed and living at 14 Richmond Cottages in Summerhill, and Thomas Lynam (no relation to Patrick), aged 17 from 2 Aberdeen Terrace, off the North Strand who worked in the printing business. At the inquest Patrick Lynam was at that stage the only one of the three with legal representation, in the form of a solicitor named Christopher Friery.

Also present at the inquest were a number of other witnesses including Samuel’s older brother William, the family member who had identified his brother’s body the previous day. He testified that Samuel had left in good health and spirits from the family home on Bride Street the previous day, which backed up the medical testimony which ruled out some underlying medical condition as being a possible cause for Samuel’s death. It was also at this point that Samuel’s profession was disclosed, he worked for the Irish Independent’s distribution section. Indeed their sister paper, the Evening Herald carried extensive coverage of the inquest that evening on its front page.

Other witnesses at the inquest included a number of O’Brien’s Middleton teammates; Thomas Ralph (24) and Edward Maguire (20) who as well as being fellow players were also neighbours of O’Brien on Bride Street, and Edward O’Dwyer of Palmerston Place, Broadstone, the self-described “inside-right” of the team. The other key witness was James Rocliffe (30) of 18 Summerhill, the referee on the day of the match.

It was Rocliffe who next gave evidence after William O’Brien. He noted how he knew neither team nor the men involved personally, he had merely been tasked with refereeing the game by the Association. He detailed the foul on O’Brien by Lynam and their subsequent fight which resulted in both players being sent off. Rocliffe then testified that as he was restarting the match he noticed several players rush off the field in the direction of O’Brien and Lynam, at this point he stopped the game and went to the nearby pavillion. Rocliffe testified that there was only one spectator and his two linesmen at the game that day. Rocliffe did not see further blows struck by either man and had not seen anyone else apart from Patrick Lynam strike Samuel O’Brien as by this stage he had retreated to the safety of the pavillion. When asked if he had seen blows struck like this before he replied:

I often saw rows and blows struck by men fighting on the street. It did not very often occur at football matches.

James Rocliffe quoted in the Evening Herald – 9th December 1924

It was the subsequent testimony from O’Brien’s teammates that was to be most incriminating, Thomas Ralph swore that upon seeing players running towards O’Brien and Lynam he witnessed two opposition players knock O’Brien to the ground and kick him. These two players were identified by Ralph as Thomas Lynam and Michael Doyle, and Ralph would later describe the accused issuing two “unmerciful kicks” to O’Brien, which he would state “were meant” intimating that they were deliberate, though both Lynam and Doyle denied this. Edward Maguire and Edward O’Dwyer confirmed that that they witnessed Michael Doyle kick O’Brien which Doyle strenuously denied at points during the inquest, loudly interjecting to profess his innocence and deny that he kicked O’Brien.

Summing up, the coroner Louis Byrne was moved to say that there had been no pre-existing animosity between the teams or individual players, and he looked upon Samuel O’Brien’s death as,

a tragic result of the blood of these boys “getting up” in the excitement of the game. He would be slow to attach any guilt to any party there on the evidence. His only regret was that when these young men went out to play football that they had not a better spirit of sportsmanship

Freeman’s Journal – December 10th 1924

The inquest jury found that the death of Samuel O’Brien was the result of injuries sustained on the football field. The case was referred to the Dublin District Court where Patrick Lynam, Thomas Lynam and Michael Doyle were to be charged with murder.

The courts

The initial hearing took place later that day with Justice George Cussen presiding, all three were charged with murder and placed on remand for a week with a substantial bail set in each case. All three young men denied the charges with Thomas Lynam saying “I never laid a hand or foot on him”.

When the case reconvened the following week similar evidence to the inquest was presented, however this time all three of the defendants had legal representation and Justice Cussen referred the murder case to the Dublin Circuit Court.

The Circuit Court hearing took place in February of 1925 with Justice Charles Drumgoole presiding. The state prosecution was entrusted to William Carrigan.

A prominent barrister from Tipperary – Carrigan was later made chair of the Government’s Committee on the Criminal Law Amendment and Juvenile Prostitution Acts – the Carrigan Committee for short. Carrigan was entrusted with examining the “moral condition” of the country and he heard testimony that highlighted issues such as child abuse, prostitution and the suggestions of their root causes; overcrowded tenements shared by large numbers of men, women and children with little privacy or security. Little of this made it into Carrigan’s report, though it’s findings were still too much for the Government to consider publish – the report was shelved by the Fianna Fáil Minister for Justice James Geoghegan.

But in February 1925 this was all still ahead of William Carrigan, his priority the three young men on trial for the alleged murder of Samuel O’Brien. Carrigan begins by questioning the character and attitude of the accused, stating that

The attitude of at least one of the prisoners was far from showing any regret… Their demeanour towards the court showed very little respect. It did not redound to their credit that they should meet the case with such levity as had been observed.

Cork Examiner – 26th February 1925

What “attitude” or “demeanour” was presented or how they were disrespectful is not specified. Once again the key witnesses examined were Dr. Murphy, house surgeon of Dr. Steevens’ Hosptial, the referee James Rocliffe and Middleton team-mates Thomas Ralph and Edward Maguire. Ralph and Maguire both stated that O’Brien had been kicked when on the ground, that O’Brien had tried to rise but collapsed into unconsciousness from which he would never awaken. And significantly both agreed that Michael Doyle had kicked O’Brien, while Ralph said that Thomas Lynam had also kicked him.

The focus of the defence was on medical evidence, honing in on the limited visible, superficial damage to the face of Samuel O’Brien, they asked Dr. Murphy whether it was possible that a fall after being struck in a “fair fight” could have caused the trauma which led to his death, rather than a kick to the head. Something Dr. Murphy agreed was possible.

Patrick Lynam testified that after being sent off he went up to offer O’Brien an apology and “make friends”, which O’Brien refused with the words “We’ll settle it here” before adopting a fighting stance, Lynam claimed this was the cause of the renewed row on the touchline behind the goal.

Michael Doyle claimed in his defence that he had gone to Patrick Lynam’s aid, wanting to take Lynam’s place as he felt that the, smaller Lynam, was “not a match” for O’Brien. Doyle strenuously denied kicking O’Brien but did recall being hit twice about the head by Thomas Ralph, claiming this dazed him and left him unable to remember anything for several minutes.

Ralph for his part admitted to hitting Doyle but claimed that he only did so in an attempt to protect O’Brien after he had been kicked, it was Ralph who then ran to the Hibernian School and returned with two National Army officers who administered First Aid to the unconscious Samuel O’Brien. It appears upon the realisation that O’Brien was seriously hurt, with the attendance of the Army officers and the calling of the ambulance the riotous scenes quickly dissipated. Thomas Lynam and Michael Doyle, perhaps suddenly realising the gravity of the situation even travelled in the ambulance with O’Brien and Ralph to the hospital.

Despite the earlier accusations made by William Carrigan about their demeanour the accused at both the circuit court trail and earlier had expressed their sorrow and commiserations on the death of Samuel O’Brien, and this was expressed by their Counsel in court. Carrigan, as prosecutor then decided to leave the case in the hand of the Judge rather than seek the verdict of a jury.

Judgement

This turn of events was one welcomed by Justice Dromgoole, saying that he was glad a jury had been “spared the necessity of trying to come to a conclusion in the case”, his judgement was reported as follows in the Irish Times:

These young men had no intention of inflicting any serious injury on the unfortunate young man, O’Brien; but at the same time, it was a pity that these games were not played in a little more sportsmanlike manner. These young men, he thought, had learned a lesson that would make them sportsmen and make them “play the game”. No one wanted to brand these young men as criminals, and it was greatly in their favour that two of them accompanied the deceased in the ambulance to hospital.

The three accused were bound to keep the peace by the judge and were charged the sum of £20 each, they were then discharged as free men.

A melancholy epilogue

Whether the family of Samuel O’Brien felt that they were served justice is unrecorded. We know that on the one year anniversary of his death Samuel’s family placed a remembrance notice to “our dear son, Samuel O’Brien… killed while playing football in Phoenix Park”, in the December 7th issue of the Evening Herald, their full notice readwhich reads:

A second notice appears beneath that of grieving parents Bridget and Samuel Snr. It is also in memory of Samuel and signed off “by his ever-affectionate Ann”, little other information is mentioned to help identify this likely girlfriend of Samuel’s but it contains a touching snippet of verse from “The Heart Bowed Down” taken from Michael William Balfe’s “The Bohemian Girl”.

Memory is the only friend,

That grief can call its own.

The O’Brien family had already suffered their fair share of tragedy by the time of Samuel’s death. His young cousin, Paul Ludlow, who also lived in the same Bride Street tenement building as the O’Brien family had died in February of 1924 of the pulmonary infection aged just 17. He was obviously particularly close to Samuel and Bridget O’Brien who continued placing notices in newspapers mourning their nephew years after his death.

Further tragedy struck the family in later years, when, just after 10 o’clock of the morning of the 1st June, 1941, their home in 46 Bride Street collapsed with many of the O’Brien family still in their top floor flat at the house. Samuel O’Brien senior, by then 72 years of age and pensioned off from his job with Guinnesses was killed in the collapse by falling masonary. His wife Bridget and daughters Georgina and Elizabeth were also injured, and of the three only Elizabeth was well enough to attend her father’s funeral three days later.

Also killed in the house collapse were Bridget Lynskey and her six month old son Noel. Bridget’s husband Francis had applied several times to the Corporation for a new home, and in a cruel twist of fate the Lynskey family had just received keys to a new Corporation house on Cooley Road in Crumlin and were due to move there in the coming days.

The story of the tenement collapse on Bride Street is perhaps less well remembered than similar events which occured on Church Street in 1913 or on Bolton Street and Fenian Street in 1963. Perhaps because the Bride Street collapse happened just a day after the bombing of the North Strand by the Luftwaffe which may have overshadowed events and dominated popular memory. Indeed the bombing of the North Strand and the impact of the Nazi bombs was cited as one possible cause for the collapse of the more than 100 year old buildings on Bride Street. Neighbouring buildings at 45 and 47 Bride Street were torn down by Dublin Corporation with many of the displaced residents moved to recently developed houses in Crumlin and Drimnagh, including the surviving O’Brien’s who eventually settled in Galtymore Road. An inquest extended sympathy to the relatives of the deceased and agreed that vibrations from the North Strand bombing coupled with the age of the house were the likely causes of the collapse, they found the landlords, the Boland family, not to have been at fault. The site of the collapsed tenement is now occupied by the National Archives building.

Almost 17 years apart Samuel O’Brien, father and son met their end in violent and unexpected circumstances, and cruel chance. One wonders if the O’Brien family having suffered so much felt they had experienced justice for their losses.

Tim Carey’s excellent book “Dublin since 1922” mentions both the Carrigan report and the Bride Street tenement collapse and is well worth a read. Michael Kielty was helpful as always in finding out details relating to Glenmore and Middleton football clubs. Thanks also to Andrew Lacey, and Amanda Lacey (née O’Brien) for further information on the O’Brien family. You can listen to this episode in podcast form here.