The Lost Clubs – Reds United

The thing about close relationships is that after years of being together one partner builds up an intimate knowledge of the other, while this is usually beneficial, bringing closeness and trust it also means that you know how to push each others buttons, sometimes even going for the nuclear option in the heat of the moment. While these rash impulses can pass their impact can sometimes be felt for years. As in personal relationships so it was with Shelbourne and the football authorities in Dublin.

In 1921 the disregard shown to Shelbourne by the IFA in the scheduling of a cup match replay for Belfast rather than in Dublin as custom dictated was the final straw for the Leinster Football Association which split with the IFA and formed what we now know as the FAI. In this case the Dublin footballing authorities rallied behind Shelbourne and their sense of injustice at the treatment by the Belfast based IFA.

Shelbourne were trendsetters in the Irish game, they were one of the first clubs outside of Belfast to pay players professionally, they were the first Dublin side to win the Irish Cup, and after the split they backed the fledgling FAI and took part in the first season of the Free State League and contested one of the first finals of the FAI Cup. However by the 1930’s relations had soured. Shelbourne were accused of poaching players in early 1934 and were fined, Shels denied the charge and ignored the fine. Things continued to escalate and in March 1934 Shels went nuclear. They wrote to the FAI (the FAI of the Free State as it was then) and informed them that they were leaving and had applied to rejoin the IFA.

Shels further refused to fulfill their fixtures in the League of Ireland Shield competition, the FAI responded by fining the club £500 for failure to play the matches. The situation reached a head in June of 1934 when at a special meeting of the FAI Council, Shelbourne were suspended from football for 12 months and the members of the Shelbourne committee were “suspended from ever taking any part in the management of any club

or affiliated body in football, under the jurisdiction of the Football

Association of the Irish Free State”.

The departure of Shels & the emergence of Reds United

With Shelbourne removed from football for at least a year (they had been blocked from joining the IFA though whether that was ever really Shels intention is doubtful) and their place in the league was awarded to Waterford, returning to the league after a gap of a couple of seasons. However, in the Leinster Senior League another club appeared, they drew their support from the same Ringsend district as Shelbourne, the featured a number of former Shelbourne players and also like Shels, they wore red. They were Reds United.

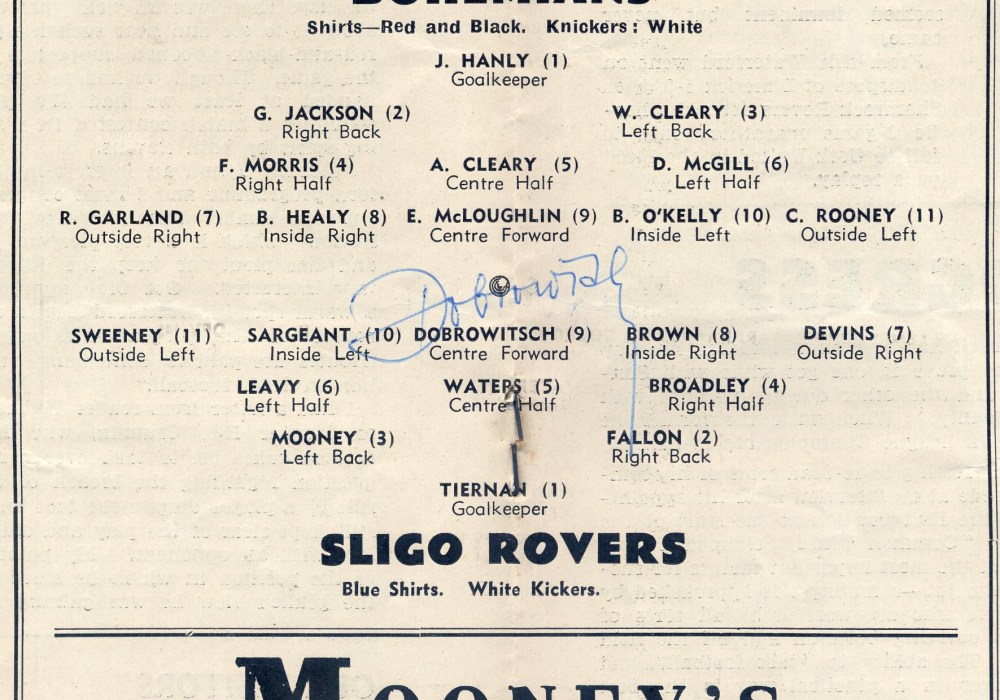

Such was the prominence of the club that some 14,000 turned up at Shelbourne Park for one of their early games, to see Reds United of the Leinster Senior League take on Bohemians in the first round of the FAI Cup in January 1935. While the side was still quite raw they surprised many by securing a 3-3 draw and a replay against the far more seasoned Bohemians.

Although still a junior club the Reds featured a core of players with league experience and had a sizeable following as demonstrated by the crowd attending the Bohs cup game. Among those players who lined out for the club was John Joe Flood who was a Ringsend local. Flood was most associated as a talented forward for the successful Shamrock Rovers teams of the 1920’s but had also featured for Leeds United, Crystal Palace and Shelbourne. He had also been capped five times by Ireland scoring four goals, which included a hat-trick on his debut against Belgium. By the time he was lining out for Reds United Flood was already in his mid-30’s but he continued to be a threat at inside forward. Indeed, even later in his career while coaching TEK United John Joe made a brief comeback as a player at the age of 51!

Joining John Joe Flood on the team was his younger brother Patrick, who played in goal, as well as former Shamrock Rovers player Tommy “Nettler” Doyle who was the younger brother of Dinny Doyle, an Irish international who ended up playing for much of his career in the United States. Incidentally all of the Doyle family (as far back as Tommy’s grandfather) had the nickname “Nettler” apparently deriving from the fact that if you gave one of them a hard tackle you would get a stinging “Nettler” of a challenge in return. Doyle had also played for Shamrock Rovers and had done well at centre forward for them after the departure of the prolific Paddy Moore to Aberdeen. He mainly featured as a forward during his time at Reds United as well.

Also signed for Reds were Maurice Cummins and Paddy Lennon two prominent half-backs who both had lined out Cork F.C. Cummins was also talented at lawn-bowling in his native Cork, he would later sign for St. James’s Gate and was part of their side that lifted the FAI Cup in the 1937-38 season. While there was a strong contingent of players from the greater Ringsend area the signing of Cummins and Lennon shows that the club were looking beyond the local, indeed two players were brought over from the Scottish Leagues.

Along with a winger named Wright who was signed from Alloa Athletic the Reds signed Willie Ouchterlonie who had enjoyed successful spells at Dundee United and Raith Rovers. Prior to joining the Reds he had been signed by Portadown F.C. but his spell up north didn’t last long before his unwieldy surname was troubling the Dublin press. He hit an impressive 20 goals for the Reds in his only season there, finishing as the club’s top scorer and third overall in the league behind Cork’s prolific Jimmy Turnbull (pictured right, scorer of a record breaking 37 league goals) and Ray Rogers of Dolphin on 23.

Along with a winger named Wright who was signed from Alloa Athletic the Reds signed Willie Ouchterlonie who had enjoyed successful spells at Dundee United and Raith Rovers. Prior to joining the Reds he had been signed by Portadown F.C. but his spell up north didn’t last long before his unwieldy surname was troubling the Dublin press. He hit an impressive 20 goals for the Reds in his only season there, finishing as the club’s top scorer and third overall in the league behind Cork’s prolific Jimmy Turnbull (pictured right, scorer of a record breaking 37 league goals) and Ray Rogers of Dolphin on 23.

By the time Reds United were signing up players from Scotland they had already triumphed in their debut season in the Leinster Senior League, as a result they and Brideville were accepted into the League of Ireland for the 1935-36 season. This might have been different had Shelbourne been successful in their application to have their suspension lifted. A motion was put before the FAI Council in June of 1935 to try and resolve the dispute between the club and the Association but this was defeated. As a result it was to be another season in the wilderness for Shels but a chance for Reds United to mix with the best.

1935-36 was to be Reds United sole season as a League club although this short spell wasn’t down to a lack of success on the field, on the contrary the Reds finished fourth in a twelve team league and ahead of the likes of Shamrock Rovers, Dundalk and Waterford. This must have come as a surprise to Rovers who had the new club as a tenant at Glenmalure Park in Milltown and who featured a couple of their erstwhile players. The lease for Shelbourne Park was held by the still-banned Shelbourne so there was no chance to replicate the bumper crowd that had seen the cup game against Bohemians there the year before. One other compromise was that for games against Rovers rather than play in Milltown these matches were moved to Dalymount Park instead. This saw a strange sort of Ringsend local derby being played out in Phibsboro on the north side of the city.

The Reds opened their league campaign with an impressive 2-0 victory over Cork with goals from Tommy Doyle and Ouchterlonie. There were several other highs to their singular league season, they did the double over their Ringsend rivals Shamrock Rovers as well as securing good wins over the likes of Drumcondra, Brideville and two wins, including a 5-0 demolition job, over Bray Unknowns. Several of their players shone during the season, along with the goals of Doyle, Oucherlonie and the veteran Flood there was talk that their Cork-born midfielder Cummins was in line for a national team call-up against the Netherlands due to his stand-out performances at left half-back.

The departure of Reds United and a Shelbourne return

Despite this impressive debut season there was to be no follow up. In June 1936 after the season had finished the league met to discuss the possible amalgamation of Reds United and Shelbourne. This didn’t seem to lead anywhere. Just a few weeks later Reds United resigned from the league, they had been unable to secure a stadium for the coming season after attempts to agree a lease on the Harold’s Cross stadium fell through.

With Reds United gone there were applications from Shelbourne and from Fearons F.C. (based in the Dublin suburb of Kimmage) for election to the league. Shels had been playing in the AUL during Reds United’s league season and in July 1936 a motion for re-admittance put forward by Shamrock Rovers was accepted unanimously at the FAI Council meeting. Similarly those Shelbourne committee members banned by the FAI were accepted back into the fold. These representations from Shamrock Rovers were important to helping Shelbourne in successfully re-applying for a place in the league for the coming season while the unlucky Fearons club were told that their day had not yet come and that they should continue their good work with a view to being elected at a future date.

While Reds United were gone from the league they did continue life as a non-league side, they played out of Ballyfermot for a time and help develop the early careers of several prominent players. The club still had strong links with Shelbourne and the wider Ringsend area, even in the late 40’s club meetings of Reds United were taking place in the Shelbourne Sports Club off Pearse Street. A club who got their league opportunity because of a falling out between Shelbourne and the FAI may only have experienced that one league season but they continued developing footballers long after the original dispute was put to bed.