Oh commemorate me where there’s football

Do we make a political statement when we as a society decide who to remember and who to forget, whose home or resting place is commemorated, and those who remained unmentioned? This is an argument as old as portraiture and statuary, but one that seems especially relevant today.

Beyond our shores, the ‘Rhodes must fall’ protest movement in South Africa, and more recently in Britain, has campaigned for the removal of statues depicting Cecil Rhodes, as part of a wider protest against institutional racial discrimination. Protests in the United States, especially in the south, have focused on the commemoration of Confederate icons of their Civil War. This has included groups calling for the removal of statues of figures such as Jefferson Davis, while also sparking some counter-protests from torch-wielding white supremacists. This has recently culminated in the outbreak of deadly violence in Charlottesville, Virginia due to the local government’s decision to remove a statue of the Confederate General and slave-owner Robert E. Lee.

In Ireland the contested nature of symbols and artwork has been especially prominent in recent years. The 12th of July commemorations by sections of the Unionist community in Northern Ireland continue to be a highly sensitive issue with occasional flashpoints, while last year saw the huge state commemoration of the 1916 Rising. While there seemed to be broad public support for the tone and content of the commemorations, they have not been immune from criticism. The commemorative wall in Glasnevin Cemetery which listed all the dead from the Rising, and included not just Irish Volunteers and civilians but also British soldiers, was vandalised with paint only a few months ago. Similarly, the statue of Irish Republican Sean Russell that stands in Fairview Park has been repeatedly been vandalised over the years by various groups, including its decapitation, due to his wartime links with Nazi Germany and indeed the Soviet Union.

These historic events and personages are marked either by significant commemorative events, like the 12th of July “festivities” with marches and bonfires, or by physical monuments, like the remembrance wall in Glasnevin, or the statue of Russell. There is also much to be said about the nature of a society in showing who is not commemorated in word, art or celebration. The Tuam babies story, of over 800 children buried in an unmarked grave in a former septic tank has dominated public discussion and forced the nation into uncomfortable reflection about our recent past. For decades, the remains of these babies and toddlers from the Sisters of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway, were disposed of as though they were detritus. It was only the work of local people, especially the meticulous research of amateur historian Catherine Corless that brought this story to national attention and meant that these deceased children could at least be remembered and perhaps suitably commemorated.

To try and consider all physical points of remembrance or indeed collective amnesia in a country, or even a city like Dublin would be a lifelong task, but living around Dublin 9 and having a particular interest I’ve decided to focus my modest talents on how our city commemorates something a little more trivial, though still important to many: its footballers.

Dublin has long been the hub for football in the Republic of Ireland, producing more international players than all other counties combined. Areas like Cabra or Ringsend could field full international XI’s out of players born in those suburbs alone. The city is also home to the main stadiums used for international matches, Lansdowne Road, which hosted its first football international in 1900, and Dalymount Park, home to Bohemian F.C. since 1901 and for many years the main home stadium for the Republic of Ireland national team after the FAI/IFA split in 1921. Other stadiums from the past and present such as Drumcondra’s Tolka Park and Glenmalure Park in Milltown also feature prominently in Irish football history. Yet the sport has also seemed controversial to some, viewed as an un-Irish, “garrison game” that was not truly representative of a post- independence Ireland. My focus is on who, and what, we as a supposedly football-loving city have chosen to commemorate.

Plaque build-up

From a quick examination, the commemoration of football in Dublin street signs and plaques is fairly limited to ex-Ireland internationals of prominence, or those sites associated with the creation of the most well-known city clubs.

In terms of playing personnel, there are three men commemorated publicly that I could find; John Giles, Liam Whelan, Patrick O’Connell and Oscar Traynor. Giles, who was the first of these to receive a commemorative plaque, is also the youngest and the only one still alive. His plaque is located in Ormond Square, Dublin 7, just off the city quays close to the house where he was born.

John Giles Irish International Footballer was born and raised in Ormond Square – Heroes come from here

The square of houses surrounds a playground area and, appropriately, the plaque is mounted on a low wall surrounding this space. It was unveiled in 2006 and the intention of the message seems to aim as inspiration for children living in this part of the city. It seems to suggest that if Johnny Giles could make it as an elite player for Manchester United and Leeds United, play for and manage Ireland, then the future should likewise be wide open for other children from this area.

Giles is of course something of a national institution, rightfully regarded as one of the country’s greatest ever players. He also managed Ireland for seven years, and later became known to successive generations due to his extended service as a newspaper, radio and television football pundit through the many highs and lows of the Irish national team.

Giles seems to still be held in affection by the vast majority of Irish football fans despite his playing or managerial involvement ending almost 40 years ago. As a player he was one of our most technically gifted and sought to encourage a more expansive style of play when Irish manager. He found success in England as a cup winner with Manchester United before his move to Leeds United, where he won two league titles, an FA Cup, League Cup and two Fairs/Uefa cups.

Liam Whelan Bridge, Connaught Street, Cabra, Dublin 7

Not a great distance from either of the two spots in Dublin that John Giles called home stands a plaque to another ex-Manchester United star, Liam Whelan. The plaque in question is on the east side of a bridge that links Connaught Street across the old railway lines, now part of the extended Luas green route, to Fassaugh Road. The bridge has been known as Liam Whelan Bridge since an act of Dublin City Council gave it that name in 2006. It is a fitting location, as the bridge is just a few seconds walk from St. Attracta Road, where Liam was born.

While Liam was an exceptional player, a back to back league winner with the stylish Manchester United side of the mid-fifties, it is more his tragic death in the Munich air disaster at the tender age of 22 for which he is most remembered. Whelan made but 98 first team appearances for Manchester United and won only 4 four senior caps for Ireland, two of those appearances made in Dalymount Park, located just yards from the bridge that bears his name.

Then as now, Manchester United were a hugely popular team in Ireland. They had been captained to FA Cup glory in 1948 by Irish international Johnny Carey, and a year later 48,000 fans packed out Dalymount Park for a testimonial match for Bohemians’ legendary trainer Charlie Harris, between Bohemians and Man Utd .

The “Busby Babes” team were famed not just for their youth but for the appealing, attacking style of football they played. Liam had been their top scorer when they won their second consecutive title in the 1956-57 season, scoring 33 goals in all competitions. His loss, and that of his team-mates symbolised the unfulfilled potential of a group of young men cut down before even reaching their prime.

Patrick O’Connell plaque at 87 Fitzroy Avenue, Dublin

The most recently unveiled football related plaque in Dublin City is in remembrance of Patrick O’Connell. He was born in Dublin in 1887, growing up on Fitzroy Avenue in Drumcondra, just a stones throw from Croke Park. Patrick was a successful footballer for Belfast Celtic before moving across the Irish Sea with spells at Sheffield Wednesday, Hull City and Manchester United. He also made six appearances for the Irish national team and was a member of the victorious Home Nations Championship winning side of the 1913-14 season, Ireland’s first victory in the competition.

Despite a relatively successful and eventful playing career (captaining Manchester United, becoming embroiled in a betting scandal, winning the Home Nations), O’Connell is best remembered for his managerial achievements. He began his managerial career as player-manager with Ashington before moving to Spain in 1922. During more than 25 years in Spain he managed a host of clubs, including Racing Santander, Real Oviedo, Barcelona and both of the major Seville clubs; Real Betis and Sevilla. O’Connell even lead Betis to their sole league title in the 1934-35 season. Strangely, despite the influence of Irish players and managers in Britain, this success is more recent than the last time an Irish manager won the League in England, namely Belfast’s Bob Kyle with Sunderland in 1913.

O’Connell is revered as a hero in Betis for this championship victory, and is similarly lauded in Barcelona as the man who saved the club from going bankrupt during the tumult of the Spanish Civil War by arranging a series of lucrative foreign tours that kept both the club coffers full and the players out of harm’s way.

The tireless activities of O’Connell’s descendants and enthusiasts has meant that this previously forgotten footballing pioneer is now commemorated not only in Dublin but in Seville, Barcelona, Belfast and in London where he is buried. The efforts of this small group has seen television and radio documentaries commissioned as well as a biography being published. In this regard O’Connell is the 3rd Manchester United player commemorated in Dublin, but the only manager. His unique achievements in Spain and his crucial role in the history of Barcelona setting him apart in an Irish footballing context.

Oscar Traynor is probably better known as a Government Minister for Fiánna Fáil between 1936 and 1961 as well as for his significant role in the revolutionary movement. He was out in 1916, was a senior figure in the Dublin Brigade during the War of Independence and took the anti-treaty side in the Civil War. He was however also a footballer of some talent and a man whose love and interest in game continued throughout his life. The opening of his Bureau of Military History witness statement contains the wonderful lines:

I was connected with football up to that and I broke with football when I saw there was something serious pending.

Traynor’s connections with football included keeping goal for Dublin side Frankfort and most notably for the great Belfast Celtic. Traynor later became President of the FAI from 1948 until his death in 1963. In the 1920s he wrote a series of impassioned articles in Football Sports Weekly defending the sport from the charges that it was a “Garrison Game” or that those who played it were somehow less Irish. In these articles he references several figures of note in the Revolutionary movement who were also prominent soccer players.

In 2016, coinciding with the centenary of the Easter Rising the residents of the Woodlawn estate (just off Oscar Traynor road) were successful in getting a plaque dedicated to Traynor installed at the entrance to the housing estate where it was unveiled by Traynor’s grandnepthew Robbie Gilligan.

Plaque to Oscar Traynor – photo from the Twitter account of his grandnephew Robbie Gilligan

A thank you to Donal Fallon for bringing the Traynor plaque to my attention.

Moore to see!

The most recent plaque dedicated to a footballer in Dublin was unveiled in April 2021 on Clonliffe Avenue, just in the shadow of Croke Park and is dedicated to Paddy Moore. Though born on Buckingham Street in 1909, Moore grew up in the Ballybough neighbourhood and called this single-storey cottage his home.

Moore is most associated with Shamrock Rovers and the plaque records his unique achievement of scoring in three FAI Cup finals and emerging on the victorious side on each occasion. Though short and stocky Moore also had a habit of scoring important goals with his head but was most renowned for his skill and finishing ability. Joe O’Reilly, who played with Moore for both Ireland and Aberdeen had this to say of him.

He was a wonderful footballer, a wonderful personality. The George Best of his time… He was a very cute player. If, in a match, things weren’t going his way, he could produce the snap of genius to turn the match around – and he was always in the right spot. I had a good understanding with him.

The comparison with best in terms of skill and technique was sadly not the only similarity, both Best and Moore developed serious problems with alcohol, and in both cases their careers at elite level were over before the age of 30. Despite this in the space of only five years and a mere nine caps Moore made history for Ireland. He scored on his debut in a 1-1 draw with Spain in Barcelona, before he and O’Reilly scored in a 2-0 win over the Netherlands in 1932. After this match Moore, O’Reilly and Jimmy Daly were all signed by Aberdeen manager Paddy Travers where Moore was an immediate success, scoring 28 goals in 30 games in his opening season for the Scottish side.

However, the following season would be less successful. While Moore still scored a respectable 18 goals in 32 appearances his strike rate had decreased and he eventually ended up going AWOL after returning to Ireland for a match against Hungary in December 1934, blaming injury and a miscommunication with Aberdeen. It seems that Moore’s problematic relationship with alcohol was impacting his performances, to the point that manager Paddy Travers had effectively chaperoned him back to Dublin for an international match against Belgium earlier in 1934. Whatever Travers did seemed to work as Paddy Moore would score all four goals in a 4-4 draw in that game. That match was Ireland’s first ever World Cup qualification game. This historic feat is also recorded on the plaque.

Moore scored again that April in the next qualifier against the Netherlands to give Ireland a 2-1 lead, however the Dutch regrouped and emerged as 5-2 victors, ending Ireland’s hopes of qualification.

One of Moore’s last games for Ireland was in 1936 against Germany in Dalymount , where the German side gave the fascist salute Irish side ran out 5-2 winners with Oldham’s Tom Davis scoring a brace on his debut, and Paddy Moore, slower, less mobile, but still perhaps the most skillful player on the pitch pulling the strings from the unusual position for him of inside left and creating three of the five goals. The German coach Otto Nerz raved about Moore and felt that he was the player that his team could learn the most from.

This was something of an Indian Summer in Moore’s career (a strange thing to say about a man aged just 26), he was back at Rovers and was instrumental in helping the Hoops win the 1936 FAI Cup His last cap for Ireland was an unispiring display in a 3-2 defeat to Hungary two months later. Injury and Moore’s well-documented problems with alcohol had, not for the last time, derailed a hugely promising football career. He finished his Ireland career with nine caps and seven goals. There were later spells with Brideville and Shelbourne before a final ill-fated return to Shamrock Rovers. Paddy Moore, one of the most celebrated and skillful footballers of his era died in 1951 just weeks before his 42nd birthday.

Paddy Moore plaque

Paddy Moore’s house

Pubs, clubs and housing estates

Many League of Ireland fans understandably feel that our domestic game gets a raw deal in wider Irish society, and with the FAI and the Irish media in particular. John Delaney’s description of the league as the “problem child” of Irish football only seemed to confirm this to the die-hard supporters of clubs around the country. However, it was not always thus. In the early days of the FAI, domestic clubs held significant sway and grandees of League of Ireland sides made up many of the committees of the FAI, including the selection committees for the national team.

Dublin has always been at the forefront of the game in this country. Again, the capital alone has comfortably provided more international players than every other county combined and the Dublin clubs have generally tended to be among the predominant clubs in the league, regardless of the era.

Upon creation of the Free State League in 1921 after the split from the IFA, the entirety of the eight-team division were Dublin based clubs. Prior to that, the only non-Ulster based clubs to compete in the Irish league for any significant amount of time came from the capital. Bohemian F.C. and Shelbourne, two clubs formed in the 1890s who remain in existence today and both their founding locations are commemorated.

The gate lodge at the North Circular Road entrance to the Phoenix Park. Bohemian FC were founded here in 1890.

Bohemian F.C. were founded on the 6th September 1890 in the Gate Lodge at the North Circular Road entrance to the Phoenix Park. Those forming the club were young men in their late teens from Bells Academy, a civil service college in North Great Georges Street, and students from the Hibernian Military School, also located in the Phoenix Park. The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory John Fitzpatrick became the first Bohs player to be capped at international level, captaining Ireland on his debut against England.

The early matches of the club were played on the nearby Polo grounds. By 1894 the club had its first major piece of silverware, the Leinster Senior Cup, defeating Dublin University 3-0 in the final. It was to be the first of six consecutive victories in the competition. Less than two years after that first victory John Fitzpatrick became the first Bohs player to be capped at international level, captaining Ireland on his debut against England.

The club continued to grow, purchasing Pisser Dignam’s field in Phibsboro as their new home ground. Dalymount Park, named after the nearby line of terrace houses remains the club’s home to this day. It also played host to dozens of cup finals and hundreds of international matches. Bohemians were founder members of the Free State league, becoming champions for the first time in 1923-24. The club have proceeded to win the title on a further ten occasions.

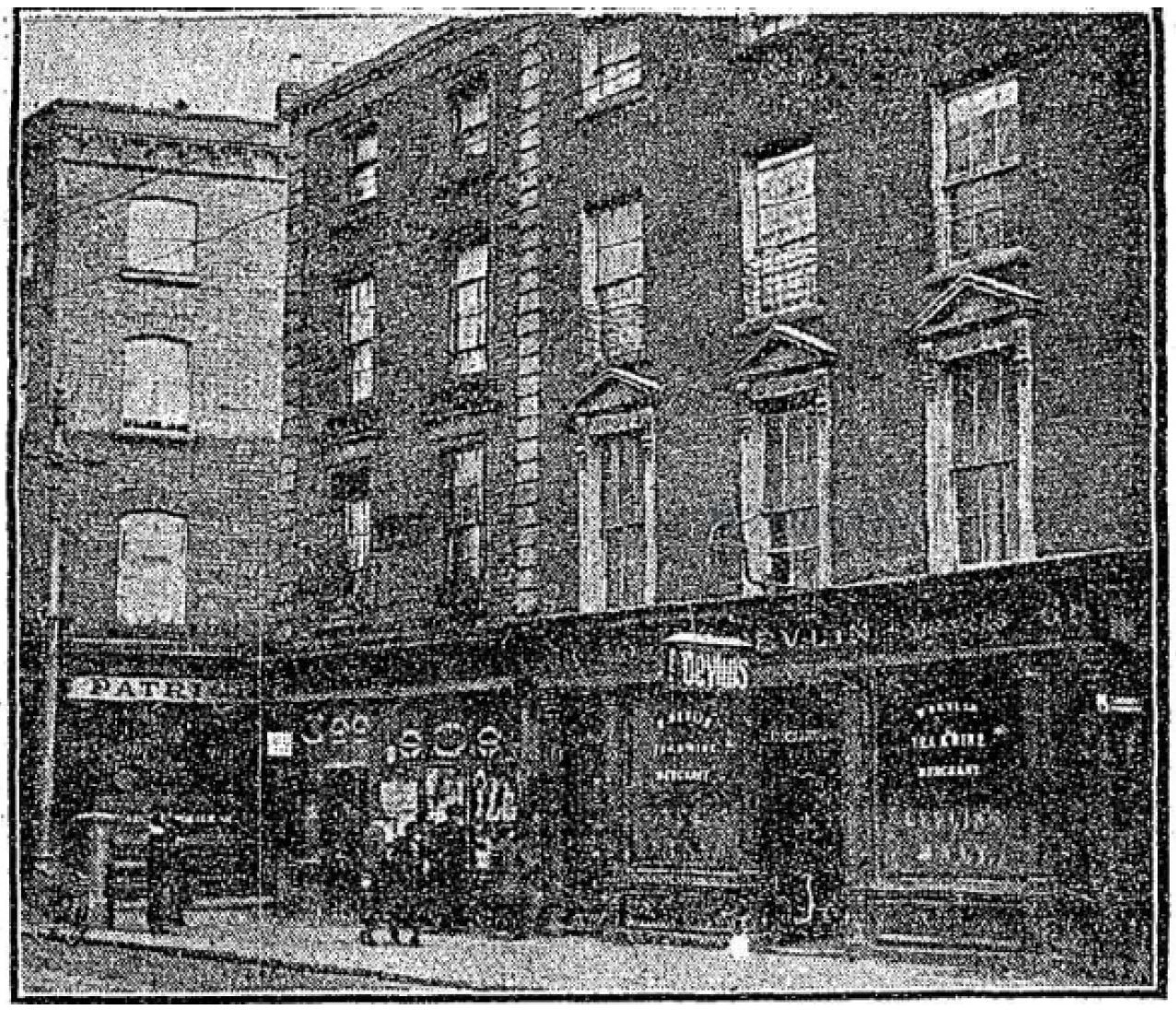

Shelbourne F.C. plaque on Slattery’s Pub

Shelbourne were founded in what is now Slattery’s Pub at the corner of South Lotts Road, Bath Avenue and Shelbourne Road in 1895 by a group of dock workers from the local Ringsend/Sandymount area. Their name was reportedly decided upon by a coin toss between the various nearby streets. By the 1902-03 season they were champions of the Leinster Senior League and by 1905 they had become one of the first Dublin clubs to begin paying players, with James Wall receiving the princely sum of a halfpenny per week!

Paying players seemed to pay dividends because by 1906 the had become the first side from outside of Ulster to win the IFA Cup beating Belfast Celtic in the final. Other triumphs would follow and to date Shelbourne have won 13 league titles and seven FAI Cups.

Commemorating the founding of Shamrock Rovers in 1901. The building is located on Irishtown Road.

Shamrock Rovers, as with Shelbourne mentioned above, took their name from a street in the local area around Ringsend, in this case Shamrock Avenue. The street as it was then no longer remains, but is roughly located where the Square is today, a small side street off Irishtown Road. The first home ground of the nascent Rovers was Ringsend Park, just to the rear of Shamrock Avenue. The club was formed at a meeting held at number 4 Irishtown Road, the home of Lar Byrne, the first secretary of Shamrock Rovers. The plaque shown above commemorates this event, and can be found on Irishtown Road near to the corner with the Square, opposite the Ringsend public library.

Irishtown Road past and present

Ringsend Park would not remain Shamrock Rovers’ permanent home for too long, as the club moved to a number of grounds in their early years and withdrew for competitive football completely on a number of occasions. However, by the early 20s, they were on the rise. They finished as runners-up in the inaugural FAI Cup final in 1921, and would win the league title a year later. By late 1926, Rovers had begun playing their matches in Glenmalure Park on the Milltown Road, and they had been playing on other pitches nearby in the years immediately preceding 1926. Glenmalure Park would remain Rovers’ home until 1987, when it was finally sold for redevelopment as a housing estate by the club’s owner, Louis Kilcoyne. The Rovers support had strongly opposed this move, and formed the pressure group KRAM (Keep Rovers At Milltown) to fight this decision. Ultimately, they were unsuccessful and the intervening years would see Rovers lead a peripatetic existence, moving to Tolka Park, Dalymount Park, the RDS and Morton Stadium amongst others, before finally relocating to their present home in Tallaght in 2009.

Glenmalure Park retains a strong significance for Rovers fans, and more than a decade after leaving, a monument commemorating their time on the Milltown Road was unveiled in 1998. In credit to Shamrock Rovers, a particularly active branch of their support have been prominent in recording and marking their heritage and history, not just with the plaque above, but also with initiatives like the fundraising for a new headstone for their former striker Paddy Moore.

Monument to Glenmalure Park on the Milltown Road at the former site of the stadium

This is pretty much the sum total of the football commemorations that I could find, although I would appreciate any other suggestions. For clarity I’ve excluded and plaques, monuments and such, that exist within football grounds and clubhouses. A quick review shows that despite the long football heritage of the city, very little of this is marked physically.

Statues of other sports stars adorn other parts of the country, from the recently unveiled statue of Sonia O’Sullivan in Cobh, to numerous GAA stars remembered in bronze in other parts of the country, hurlers Nicky Rackard in Wexford Town and Ollie Walsh in Thomastown being two personal favourites. There is a statue of Spanish golfer Seve Ballesteros at Heritage golf club in Co. Laois, and even our four-legged friends have been immortalised, with the legendary racing greyhound Mick the Miller getting pride of place in the centre of Killeigh, Co. Offaly and another of his ancestor Master McGrath just outside Dungarvan. In terms of football, there is a statue of big Jack Charlton in Cork Airport, but if you didn’t know him as the former Irish manager you might think it commemorates a noted angler.

So what have we learned? In Dublin, to be a footballer and receive a physical commemoration, it really helps if you’ve played for Manchester United! The city’s three biggest clubs are all remembered at their places of birth, while Rovers’ home ground at their peak has also been commemorated in granite and bronze. Perhaps Tolka Park will receive similar treatment if and when it is redeveloped? I for one would certainly hope so.

I’ll end on one final commemorative plaque. This one is on Parnell Square East and marks the birth place of the inimitable Oliver St. John Gogarty. The plaque commemorates Gogarty as a Surgeon, Poet and Statesman. Plenty more terms could be added. He was the inspiration for the character Buck Mulligan in James Joyce’s Ulysses, and he was also a fine sportsman, in swimming, cricket and indeed football. Gogarty was a Bohemian F.C. player from 1896 until at least 1898 and featured as a forward in the clubs first team. It may not be as a footballer that he is best remembered but it was certainly another string to his bow.